- Your favorite DSGE sucks

- Paris overtakes London as Europe’s biggest stock exchange (but read the fine print)

- SNB not alone with a balance sheet loss

- The fiscal cost of QE (about €600 billion)

- Shifting economies in the EU (cartograms showing GDP per country)

- Benjamin Hennig’s website has many brilliant cartograms, e.g. on diamond production, world population and GDP, inequality in Europe, wealth on the British Isles

- Create cartograms online

- UBS strategy defies crisis

- Cost of mitigating high energy prices

Tag: economics

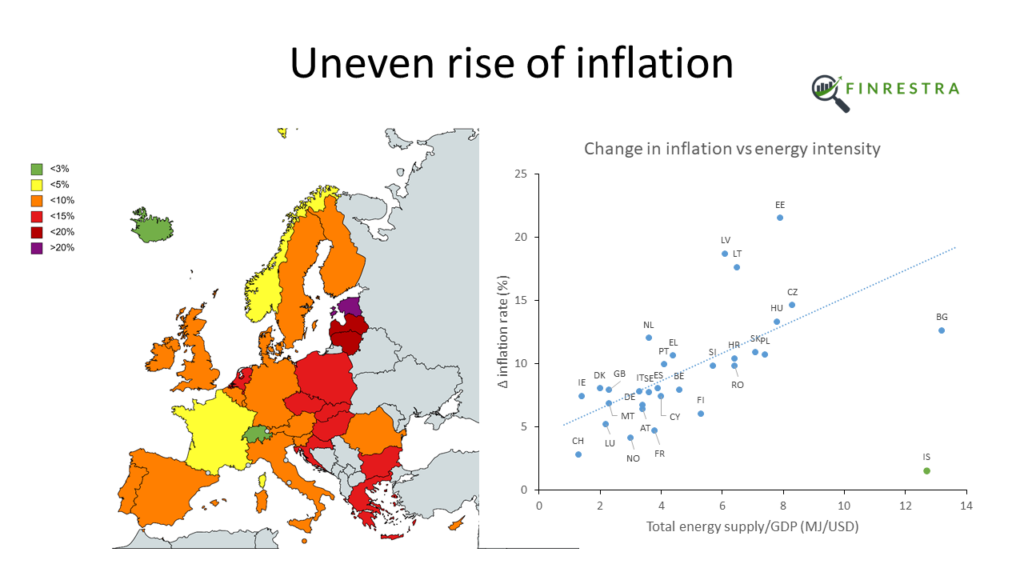

Energy intensity is driving the uneven inflation in Europe. Unemployment, deficits, debt and interest rates are not.

Video version here:

This post contains links to sources and some extra analyses.

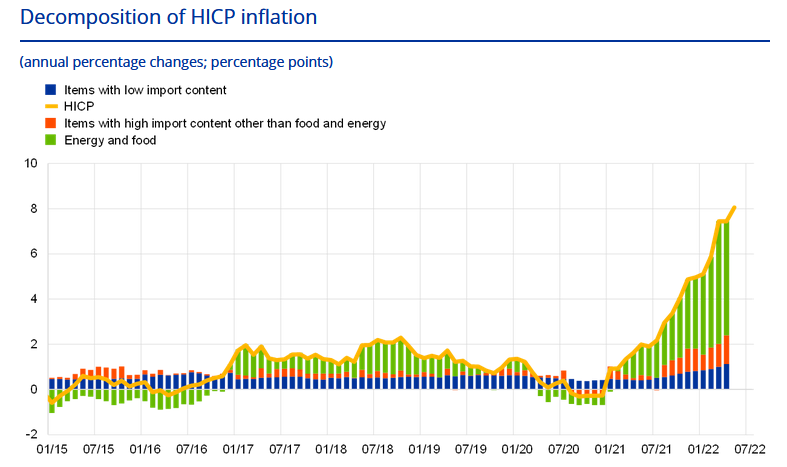

After years of low inflation, inflation in Europe has gone through the roof. Germany is experiencing the highest inflation in 70 years.

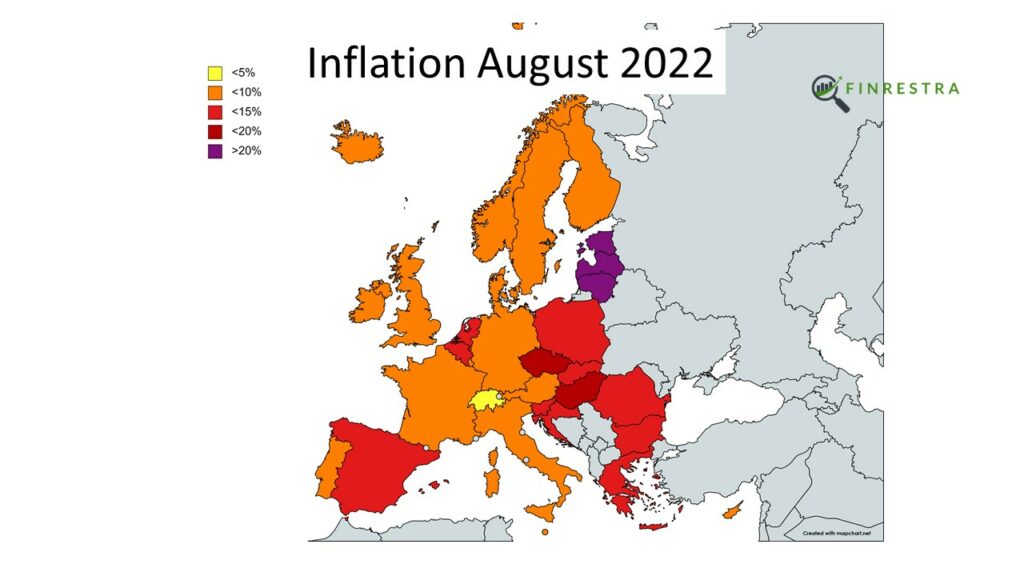

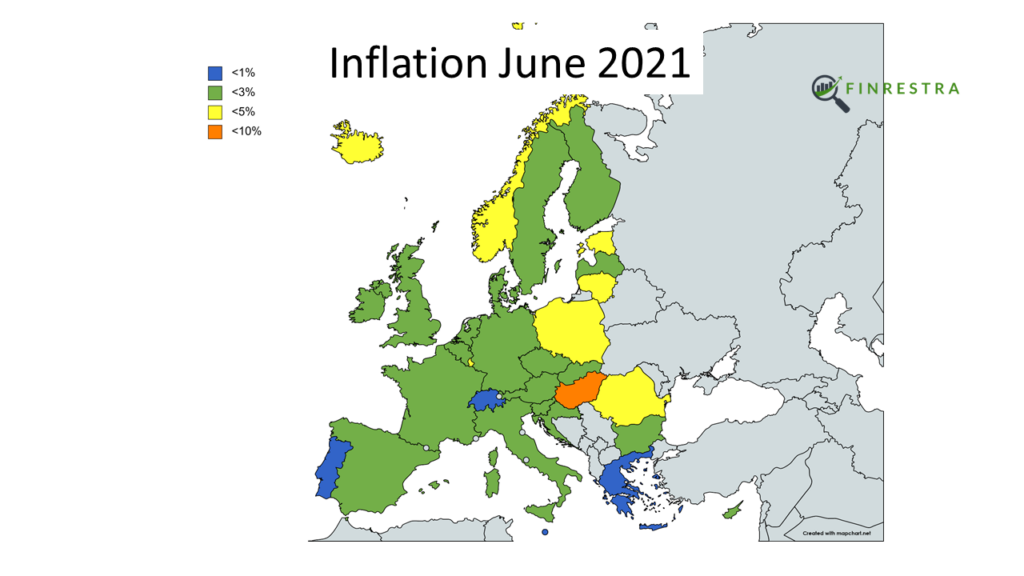

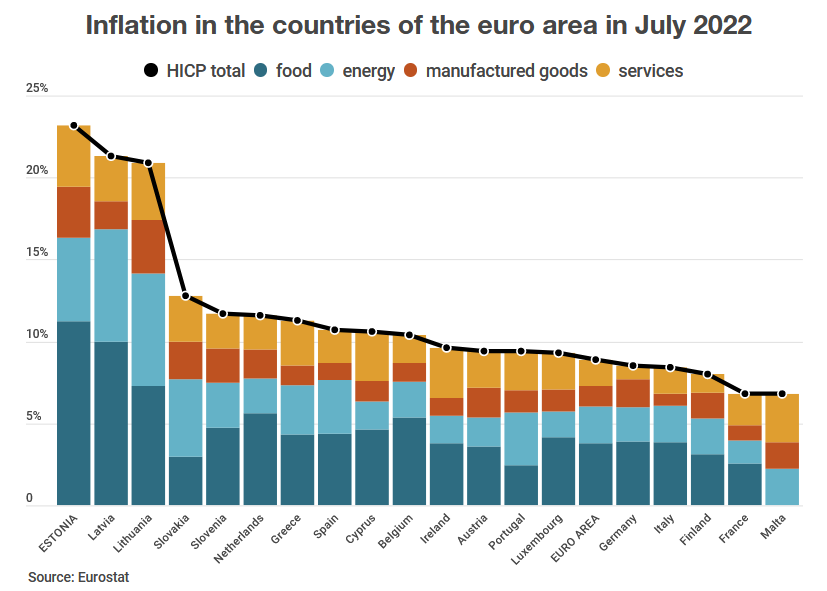

In June 2021, inflation was still close to 2%. In August 2022, it was above 10% in the European Union (EU) as a whole. But that number hides a remarkable divergence between countries. In Estonia, inflation reached a stunning 25% in August 2022. In France, it was 6.6%. In Switzerland, not an EU member state, inflation was just 3.3%.

A year before, in June 2021, inflation was very close to 2% in most European countries. With 5.3%, Hungary had the highest inflation. Inflation was lowest in Portugal, at -0.6%.

In this post, we’ll look at the change of inflation in 31 countries: the 27 member states of the EU, and the United Kingdom (UK), Norway, Switzerland and Iceland.

How can we explain the dramatic, uneven rise in inflation?

Energy intensity

Consumers are paying a lot more for energy than they used to. Companies also face higher energy bills, which has an impact on the price of their goods and services.

But energy prices are set on international markets, e.g. for oil, gas, coal and electricity. Why doesn’t expensive energy result in a similar rise of inflation across Europe?

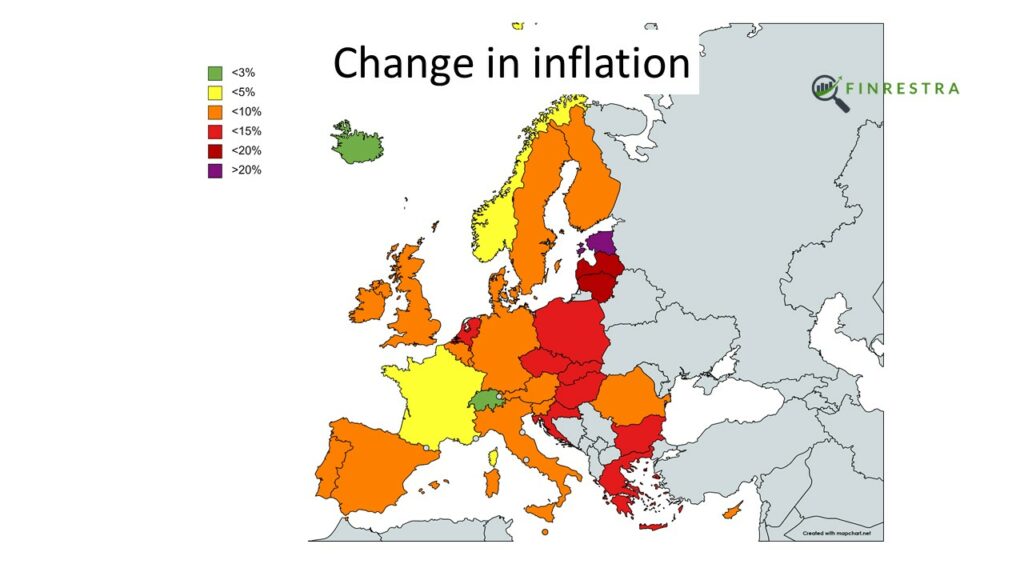

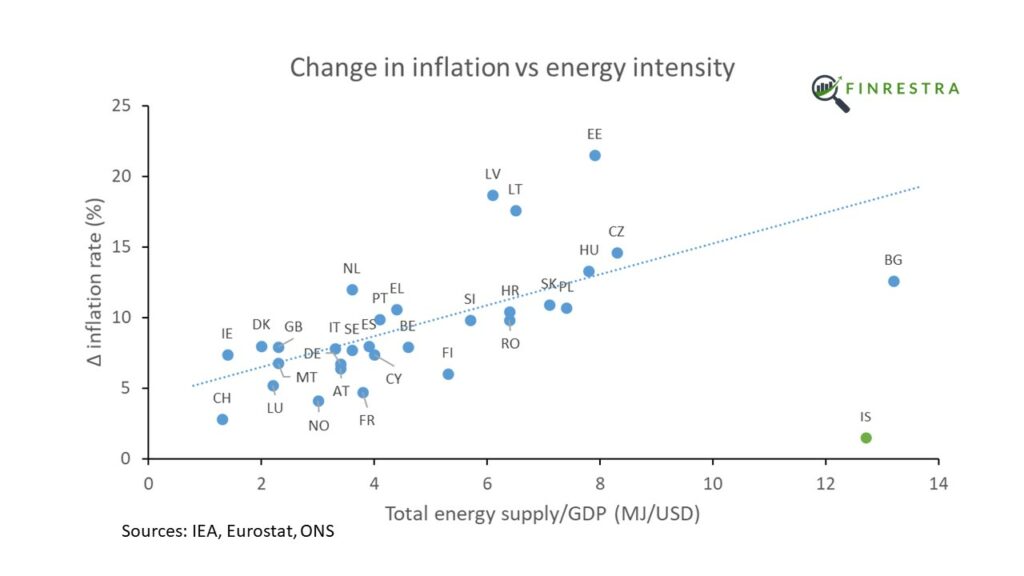

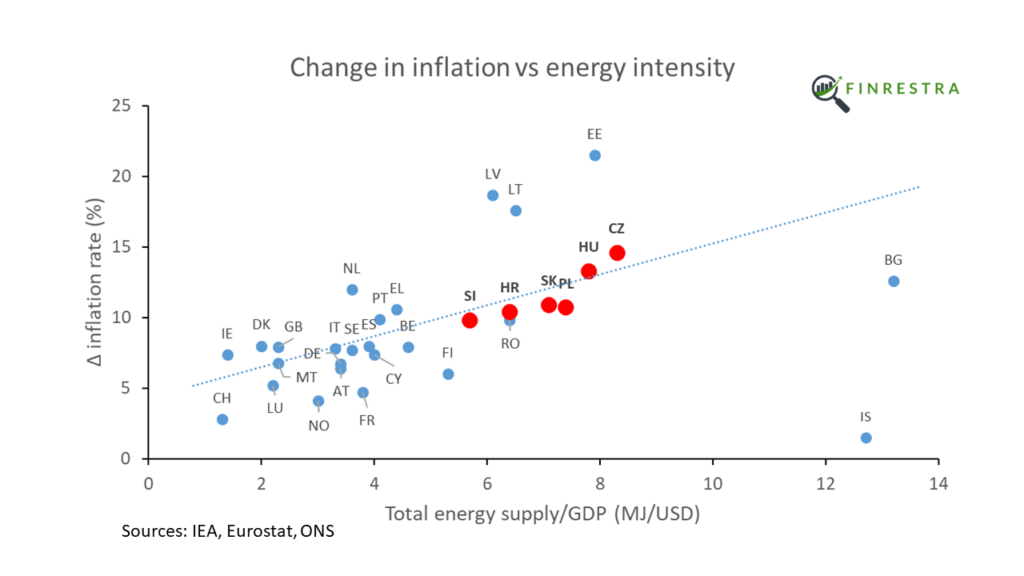

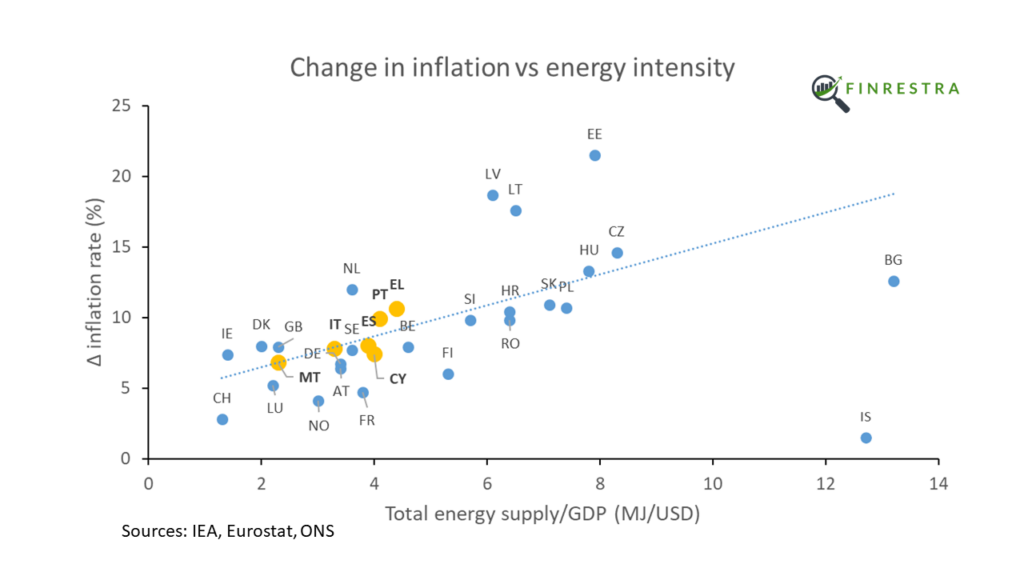

As the following figure shows, there is a strong correlation1 between the rise of inflation and the ratio of energy use to GDP2. As a general rule, the more energy a country needs to produce a dollar of economic output, the higher its inflation. Countries in Central and Eastern Europe have higher energy intensities and higher inflation rates than their Western European neighbors.

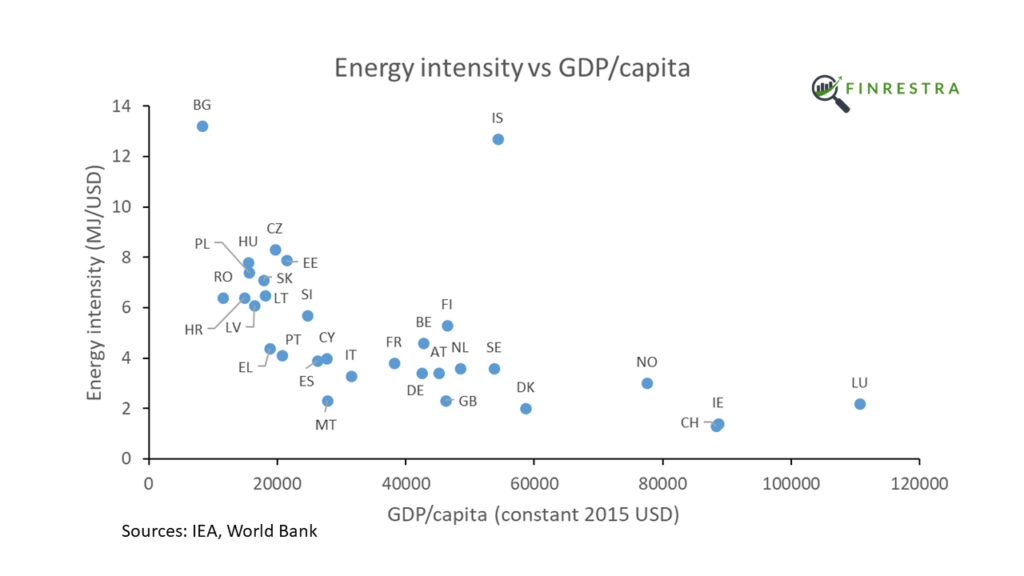

Countries with a lower GDP per capita tend to be more energy intensive.

So it’s not surprising that Central and Eastern European countries, who are relatively poor, are experiencing higher inflation than the West3.

But it’s not just an East-West story. Even within regions with similar GDP per capita, the more energy intensive countries experience higher inflation. For example Central Europe4,

Southern Europe5,

and the Baltics6.

The picture is less clear in Western Europe. The energy intensity of Luxembourg and Ireland is distorted by the denominator (small countries with a very high GDP per capita due to the presence of international companies). France already limited energy prices in 2021. The Nordic countries are just weird ¯_(ツ)_/¯

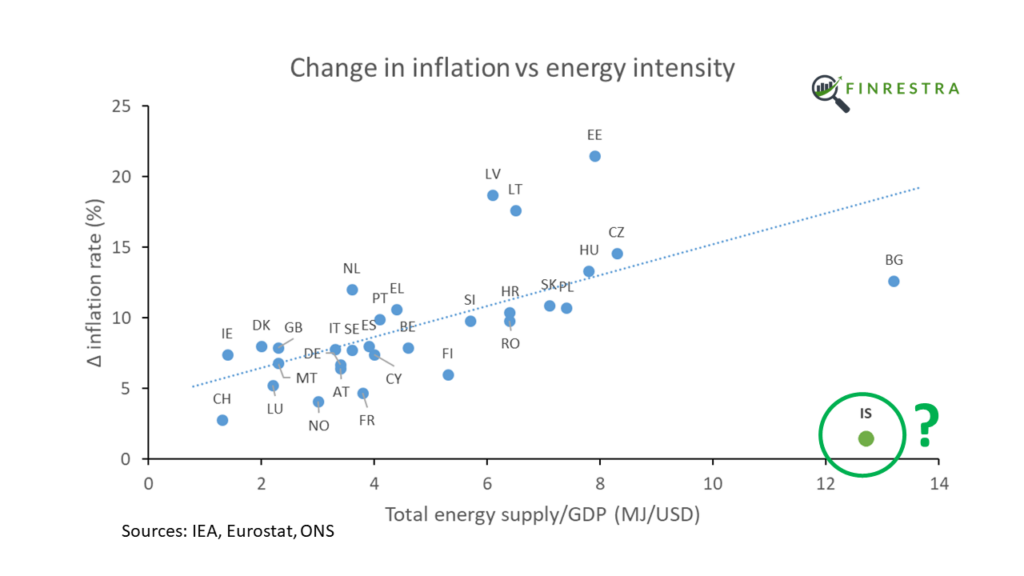

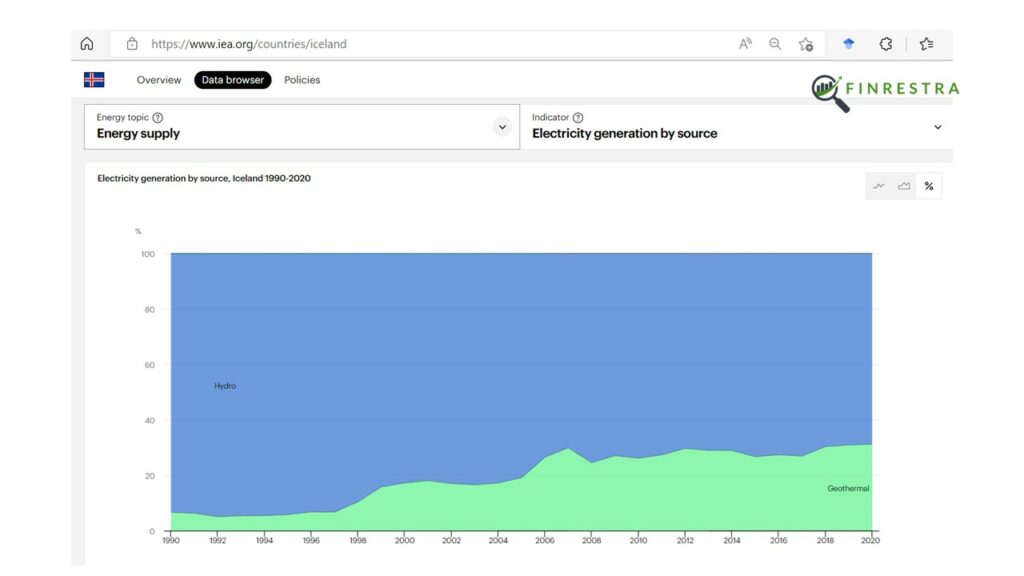

What’s going on in Iceland? Iceland is a rich country with an abnormally high energy use. Why doesn’t this result in much higher inflation?

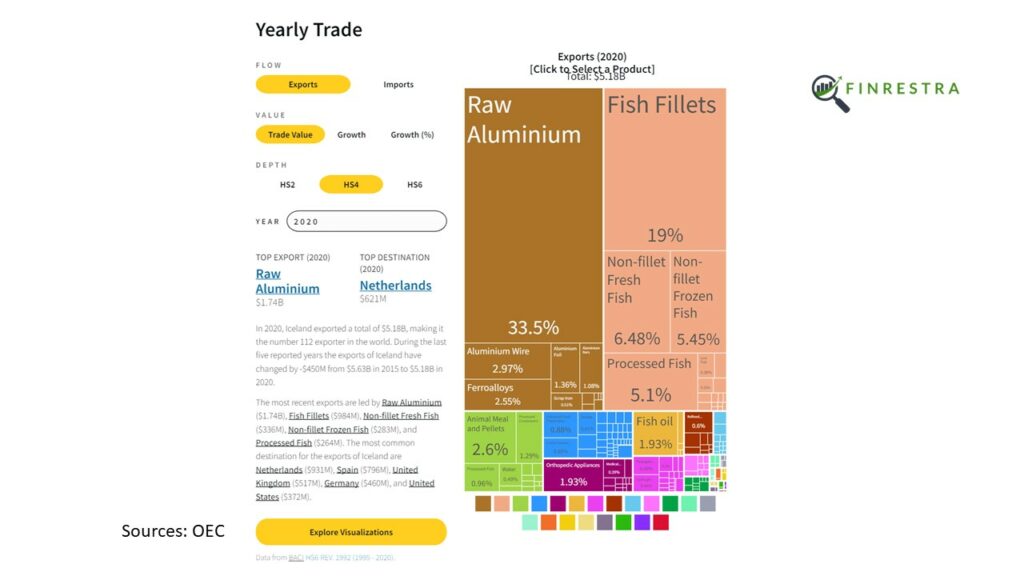

Although Iceland is a small nation, it’s a big producer of aluminum.

Making aluminum requires a lot of electricity. But all of Iceland’s electricity is generated from renewable sources.

So the Icelandic economy is less affected by higher fossil fuel prices than the rest of Europe. Fossil-free electricity also seems to be the explanation for the very low inflation in Switzerland.

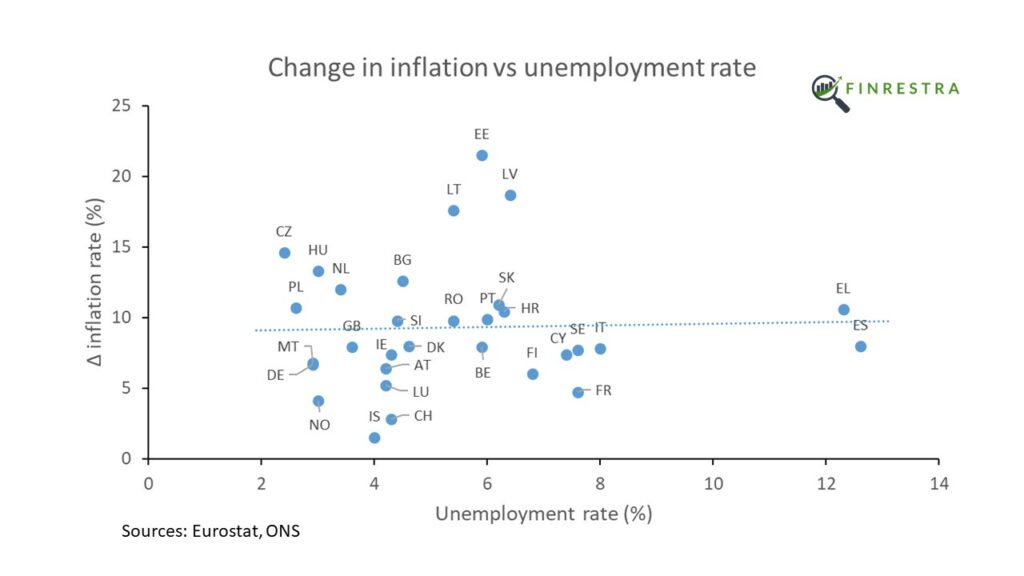

Unemployment

What other factors could contribute to the rise of inflation?

According to economic theory (NAIRU, Phillips curve), when unemployment is “too low”, workers demand higher wages. And higher wages lead to higher prices.

However, there is no correlation7 between unemployment8 and the change of inflation in Europe.

Inflation rose more in Spain and Greece than it did in Germany, although the German unemployment rate is much lower.

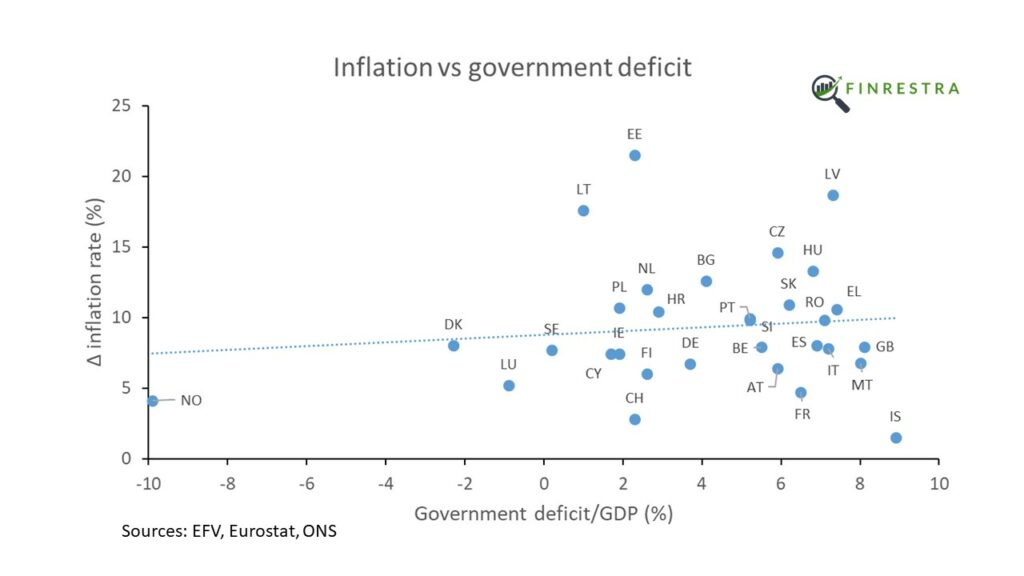

Government deficits and debt

Do deficits cause inflation (Fiscal theory of the price level)? It makes intuitive sense that if the government spends more money into the economy than it takes away with taxes, this deficit leads to inflation.

However, there is no correlation9 between government deficits10 and the rise in inflation.

Denmark and the UK have the same change in inflation, although the Danish government ran a budget surplus in 2021, while the British had an 8.1% deficit. Finland and Estonia had similar deficits, but their inflation numbers are very different.

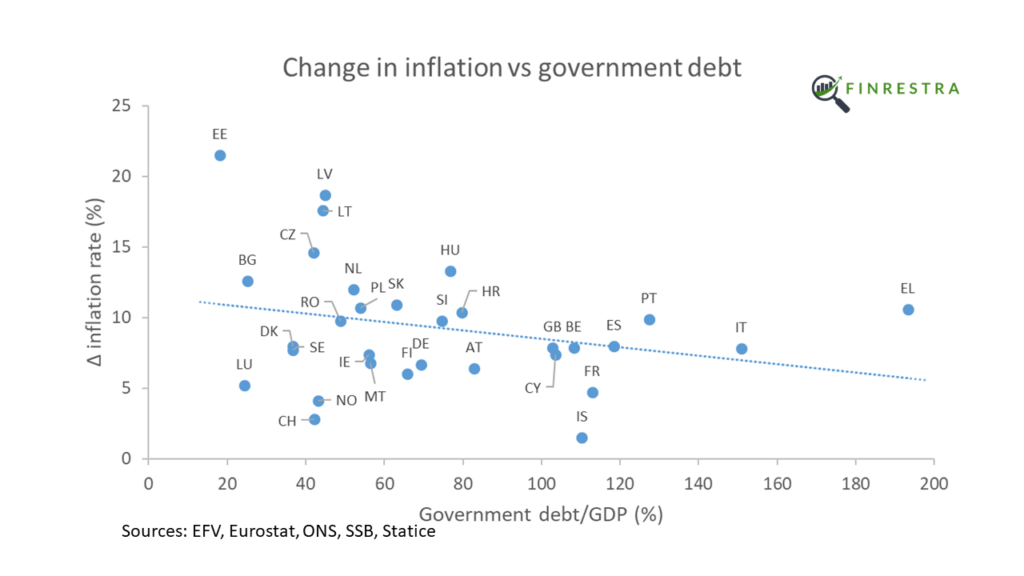

What about public debt? Maybe inflation goes up because people lose confidence in the sustainability of the debt. Or because governments choose to inflate away the debt.

However, there is a slightly negative relation11 between government debt and inflation12.

Greece, with its massive government debt, has experienced a smaller rise in inflation than the Baltic countries, where government debt is very low. Estonia has both the lowest government debt to GDP, and the highest inflation in Europe! Inflation is higher in the Netherlands than it is in Italy, although Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio is almost 100 percentage points higher.

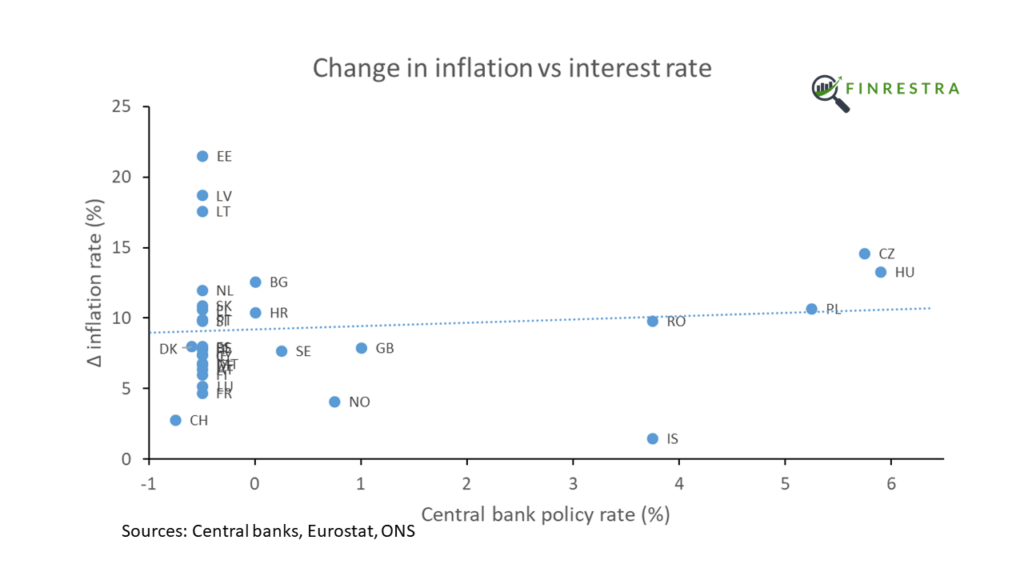

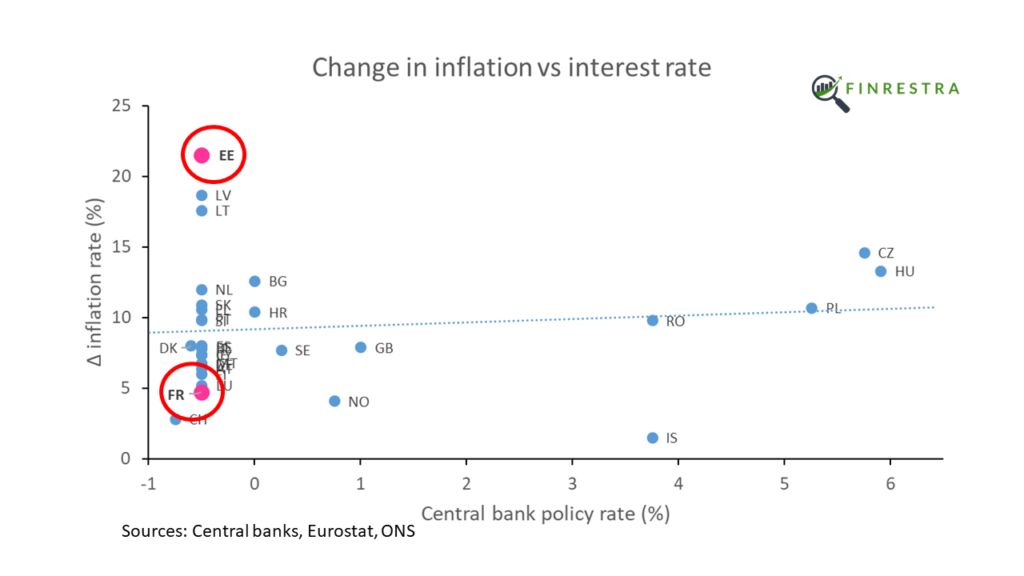

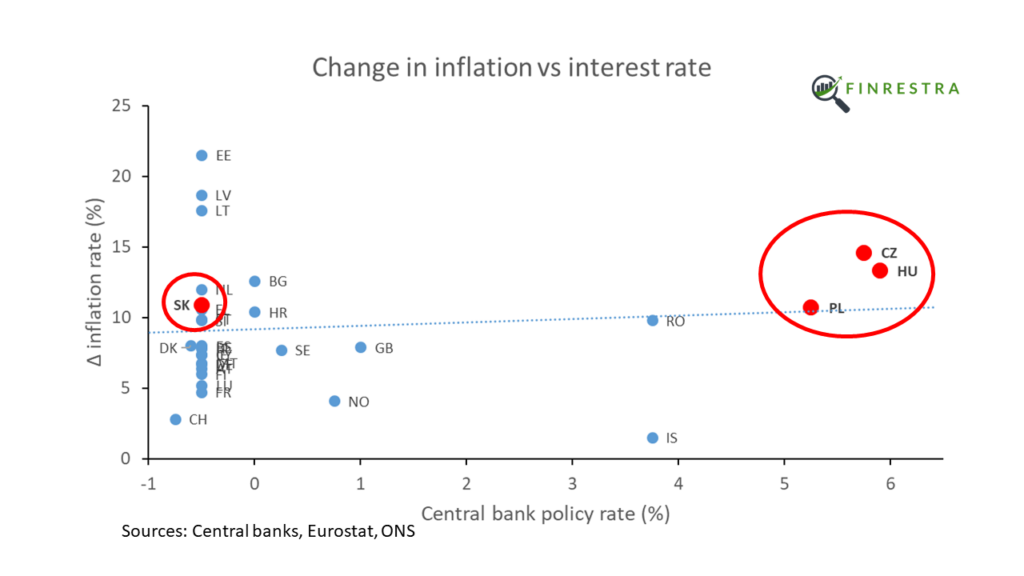

Central bank interest rates

Central bankers try to control inflation by changing interest rates. By influencing how expensive it is to borrow money, they influence prices of goods and services.

The picture shows central bank policy rates13 on June 1, 2022. Since that time, central banks have raised interest rates in an attempt to tamp down inflation.

But it’s not clear that interest rates have an effect on Europe’s inflation. In the euro area, where the ECB sets monetary policy for all 19 member states, inflation rose by 4.7% in France and 21.5% in Estonia.

In Slovakia, a country with a negative interest rate, the rise in inflation (+10.9%) is similar to neighboring Czech Republic (+14.6%), Hungary (+13.3%) and Poland (+10.7%), where policy rates were over 5%.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Europe’s worse inflation in generations is driven by energy. Conventional factors monitored by central banks don’t seem to play a role.

Contact

This work started as a small project I did during the summer, using June 2022 inflation instead of the change of inflation (see tweet below). In this post and in the video, I used the latest available data. I also added six countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Malta, Romania14 and Iceland) to the dataset.

If you have any questions or suggestions about this work, you can find me on Twitter @janmusschoot or mail me at jan.musschoot@finrestra.com.

For my professional services, please contact me on Linkedin or mail me at jan.musschoot@finrestra.com.

Statistical robustness

Twitter user Rasmus checked the data points I posted in June. His test shows that the regression line slope is different from zero:

Some further thoughts about energy prices

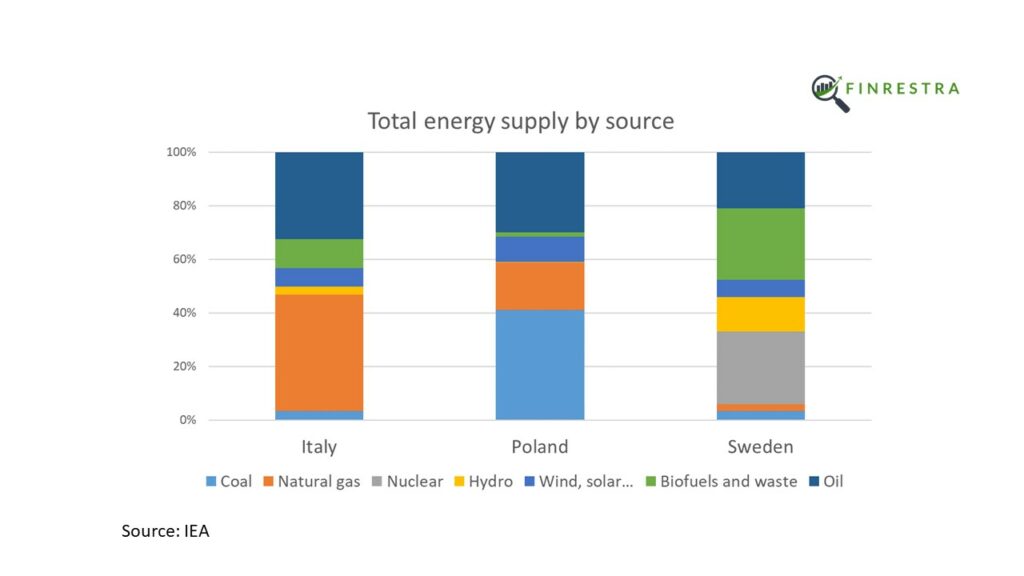

It is remarkable that there is such a strong correlation between inflation and energy intensity, given the different energy mix between countries. For example, natural gas is the most important fuel in Italy. Poland mostly burns coal, while Sweden relies on wood. While natural gas and coal prices are up hundreds of percent, that’s not the case for oil or nuclear.

I suspect the strong relation is due to electricity prices, which are often determined by the price of natural gas.

Other complicating factors that my analysis doesn’t take into account are price caps for energy (e.g. France), and the energy intensity of exporting industries (which should have less of an effect on domestic consumer price inflation).

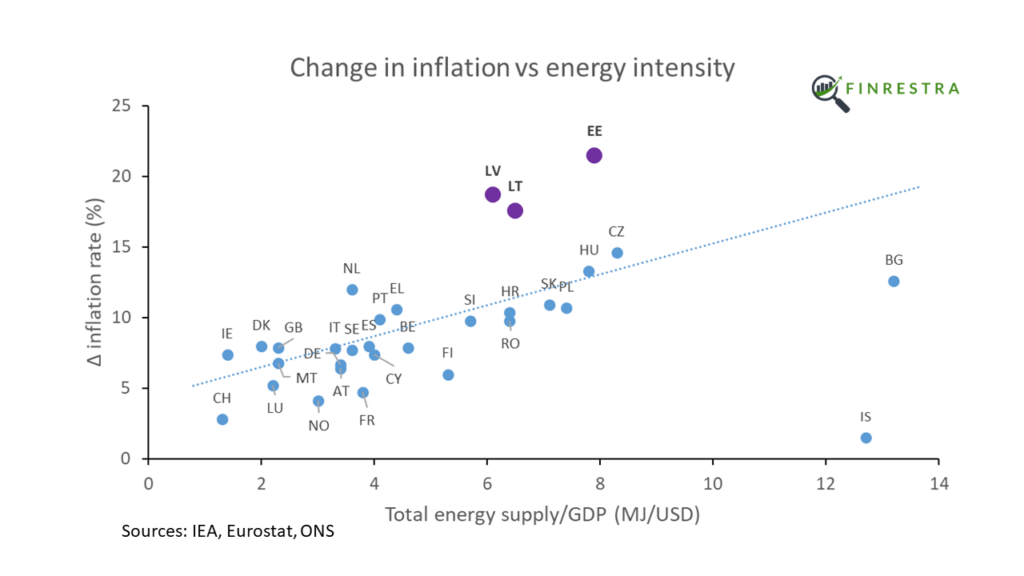

What’s the deal with the Baltics?

The three Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) are outliers. Their inflation is much higher than we’d expect based on their energy intensity. It’s not obvious that the fact that they share a border with Russia is the explanation. Finland, a euro country like the Baltics, also borders on Russia and has a relatively low inflation.

According to the central bank of Estonia:

There are several reasons why inflation is higher in the Baltic states than the average in the euro area. The share of energy goods in the purchasing basket of consumers in the Baltic states is larger, which has affected the rise in the price of the consumer basket. Natural gas and electricity were a little cheaper in the region before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but prices have now caught up to those in other countries.15

Useful energy-related links:

Energy statistics – an overview (Eurostat)

From where do we import energy? (Eurostat)

European natural gas imports (Bruegel)

Carbon intensity electricity (Electricity maps)

Electricity prices (euenergy.live)

Real-time electricity tracker (IEA)

National policies to shield consumers from rising energy prices (Bruegel)

The US debt ceiling and the trillion dollar platinum coin (Finrestra podcast episode 2 transcript)

Listen to this episode on Spotify, Apple or YouTube!

Transcript1:

“Here’s what you need to know about the debt ceiling.

The main player in this drama is the US congress. Congress is the legislative body of the federal government, similar to parliaments in Europe. Congress makes the laws.

In particular, Congress specified how much the US should spend on things like social security and the military. Congress also passed laws on taxation.

These laws are executed by the Treasury, what we call the Ministry of Finance in Europe.

Because expenditures exceed the tax revenue approved by Congress, the Treasury needs to borrow the difference. So US government debt goes up.

And that’s where the debt ceiling comes in.

In addition to laws on spending and taxation, Congress also passed a law on the maximum level of government debt. This so-called “debt ceiling” is currently somewhat above 28 trillion dollars.

If Congress doesn’t raise the debt ceiling, the Treasury has a huge problem.

To comply with the law, Treasury has to spend money on existing programs. But according to the debt ceiling, it cannot borrow any more money. And Treasury cannot create new taxes, that’s the responsibility of Congress.

So it seems that the Treasury is trapped in an impossible trinity, where it cannot satisfy the three demands of Congress (spend, tax, debt ceiling) at the same time.

But some smart lawyers have discovered a loophole.

Treasury has the right to make money. Specifically, the Treasury can mint coins from platinum, a precious metal. But the value of the coins isn’t in the metal. The coin can be whatever value the Treasury says it is. Just like a 100 dollar bill is worth a hundred dollars because it is issued by the Federal Reserve, not because the material is worth a hundred dollars.

So when Congress doesn’t raise the debt ceiling, Treasury can make a trillion dollar platinum coin. That way, it has extra money to keep paying the existing spending programs approved by Congress, without increasing the debt.

There’s a website, mintthecoin.org, which has answers to a lot of questions on the proposal to mint a trillion dollar coin. For example, whether it’s legal (yes, it is) and whether it would lead to hyperinflation (no, it won’t).

I hope you enjoyed this episode of the Finrestra Podcast. Don’t forget to listen to our first episode with Uuree Batsaikhan of Positive Money Europe. You can follow me on Twitter @janmusschoot, that’s @ j a n m u s s c h o o t. Our website is finrestra.com. Thanks for listening!”

Are higher interest rates going to crash the economy? A quick calculation suggests no

Even with inflation at 5%, some people believe that higher interest rates will crash the economy. Is this 2011 all over again1?

As I explained on Twitter, increases in debt servicing costs are small compared to rises of other production costs (e.g. labor). So if the economy does crash after rate hikes, it must be because of some other/indirect cause.

What do economists know?

Three articles casting doubt on the validity of economic knowledge.

Dirk Bezemer describes the shifting opinions of Dutch economists. Since the coronavirus pandemic, the majority thinks government debt can rise to 90% of GDP without causing problems. Few believe the 60% debt-to-GDP ratio of the Maastricht Treaty is a sensible ceiling. Compare that to December 2019, when planners at the CPB wrote that ‘sustainable’ government finances would stabilize debt at 25% of GDP. Thinking has also shifted about topics like the flexibility of the labor market, taxation and the climate responsibilities of the ECB. All of this raises questions about what economists really “know”. Is all of it politics dressed up as “neutral science”? Bezemer exposes the secret:

“The consensus among policy economists, including those at universities and research institutions, appears to correspond surprisingly well with current policy. That what becomes politically opportune, or simply happens, is suddenly embraced by many economists as being sensible and responsible.” (own translation)

JW Mason is pessimistic about macroeconomic theory:

“What is taught in today’s graduate programs as macroeconomics is entirely useless for the kinds of questions we are interested in. (…) [Macroeconomics education] provides no preparation whatsoever for thinking about the substantive questions we are interested in. It’s not that this or that assumption is unrealistic. It is that there is no point of contact between the world of these models and the real economies that we live in.”

This explains Bezemer’s secret: when the models don’t put constraints on what we expect to happen in the real world1, it’s convenient to follow popular opinion of the people in charge.2 Instead of rigorous science, policymaking relies on “a kind of folk wisdom — low unemployment leads to inflation, public deficits lead to higher interest rates, etc.”. Like Bezemer, Mason concludes that

Keynes got a lot of things right, but one thing I think he got wrong was that “practical men are slaves to some defunct economist.” The relationship is more often the other way round. When practical people come to think about economy in new ways, economic theory eventually follows.

Bezemer and Mason are not two disgruntled outliers. A survey of almost 10,000 economic researchers found that most are dissatisfied with the status quo, in terms of research topics and objectives.

Interesting podcast episodes

Latest update: July 26, 2021

- John Tuttle (NYSE) on Odd Lots about direct listings

- Grigorios Konstantellos on Voices of the Belt and Road about Chinese investments in the port of Piraeus

- Tom Burgis on The Chartcast about dirty money

- Meltem Demirors and Michael Saylor on Odd Lots about bitcoin

- Bevis Watts (Triodos Bank UK) on Green is the New Finance about retail banking

- Exit Scam, a podcast series about the dead (?) founder of crypto exchange Quadriga

- Rui Ma and Ying Lu on Acquired about Chinese tech companies, consumer trends, and that “rural China” doesn’t mean what you think it means

- EU Untangled about the European Green Deal

- Alexandra Scaggs on Macro & Cheese about financial journalism

- How a tax haven is leading the race to privatise space (Talks about the economy of Luxembourg, not just space)

- Nederland: narco- of surveillancestaat

- The career rules you didn’t learn at school

- Lisa McDermott (ABN AMRO) on Redefining Energy about project finance

Random reads winter 2020

- Russian elites and offshore companies (OCCRP)

- Mongolian workers, Scottish managers: Foxconn in the Czech Republic (Ning Hui for Echowall)

- Belgian carbon taxes are a mess (Ruben Baetens)

- Banque Havilland and the UAE (Bloomberg)

- Intuitive guide to convolution (Better Explained)

- Intangible assets and invisible value (Adam Keesling/Napkin Math)

- Is central bank digital currency (CBDC) legal? (IMF)

Banking update August-September 2020

- ABN AMRO exits all its non-European corporate banking activities

- CaixaBank and Bankia are planning a merger

- HSBC wants to sell its French retail network

- Rumors of a merger between Credit Suisse and UBS

The strategy of European banks ever since the Global Financial Crisis has been to focus on profitability1. How do you achieve a higher return on equity? There are two commonly followed options. Either you cut costs, e.g. by merging banks in the same geography and closing down the redundant branches. Or you sell the business, especially when you’re an also-ran outside of your home market.

An EU super rebate would solve a lot of problems

European Union leaders agreed on a package of measures to support the economy after the damage done by Covid-19.

The summit took four days, because of tensions between member states that will be net payers and those that will be net receivers of EU funds.

However, I had a more elegant alternative, as I explained on Twitter (thread):

The EU missed an opportunity to provide macroeconomic support that matches the size of the corona shock, to increase safe assets and to avoid transfers between member states.

Government debt and inflation

Do deficits automatically lead to default or high inflation? No.

Here are some good reads:

Will deficit spending lead to inflation? There is a difference between developed and developing countries.

Who pays for this? How the United States dealt with its national debt after the Second World War.

Historical lessons from large increases in government debt. The debt was set aside in a sinking fund for repayment at a later date.