- Your favorite DSGE sucks

- Paris overtakes London as Europe’s biggest stock exchange (but read the fine print)

- SNB not alone with a balance sheet loss

- The fiscal cost of QE (about €600 billion)

- Shifting economies in the EU (cartograms showing GDP per country)

- Benjamin Hennig’s website has many brilliant cartograms, e.g. on diamond production, world population and GDP, inequality in Europe, wealth on the British Isles

- Create cartograms online

- UBS strategy defies crisis

- Cost of mitigating high energy prices

Tag: central banks

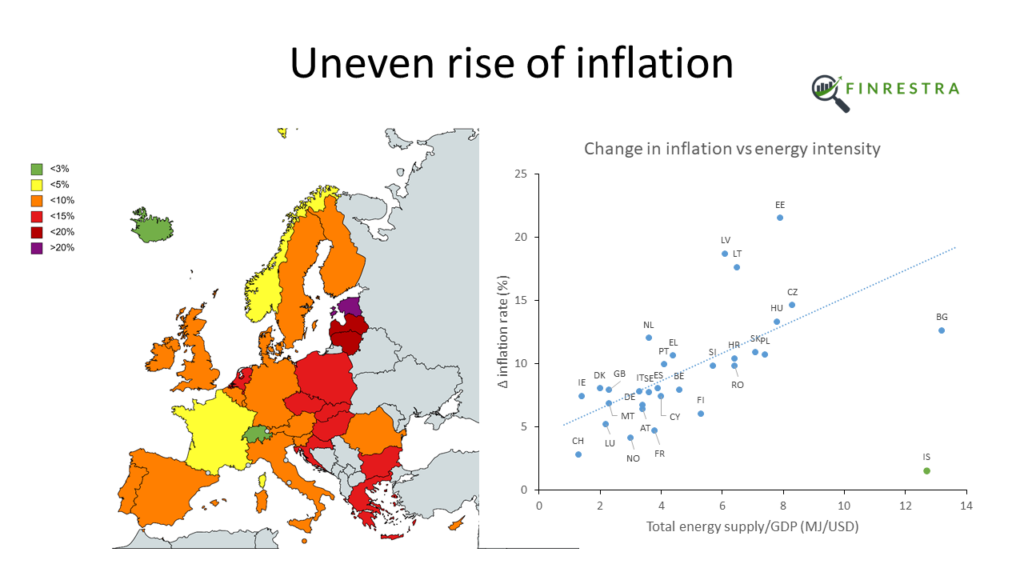

Energy intensity is driving the uneven inflation in Europe. Unemployment, deficits, debt and interest rates are not.

Video version here:

This post contains links to sources and some extra analyses.

After years of low inflation, inflation in Europe has gone through the roof. Germany is experiencing the highest inflation in 70 years.

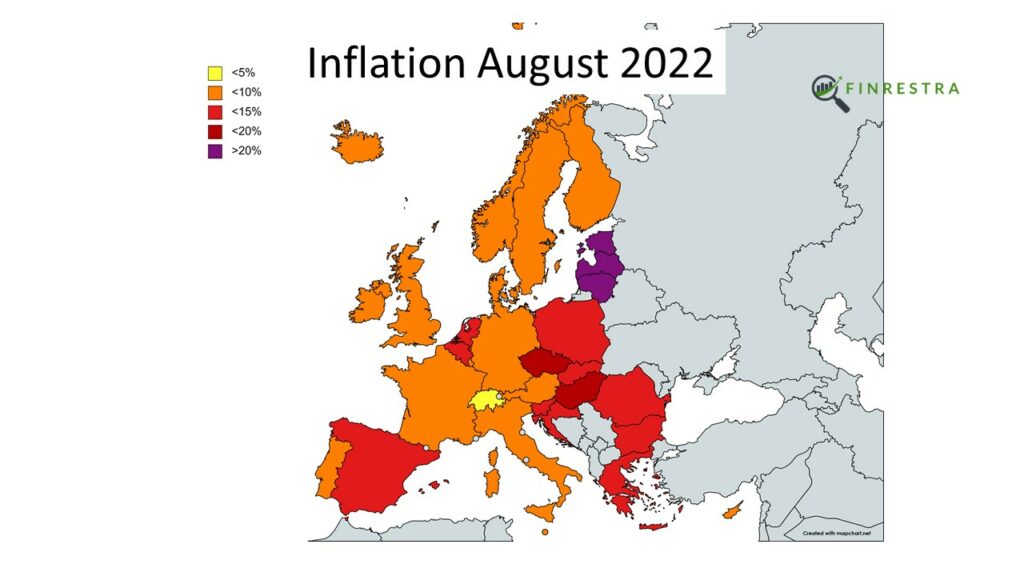

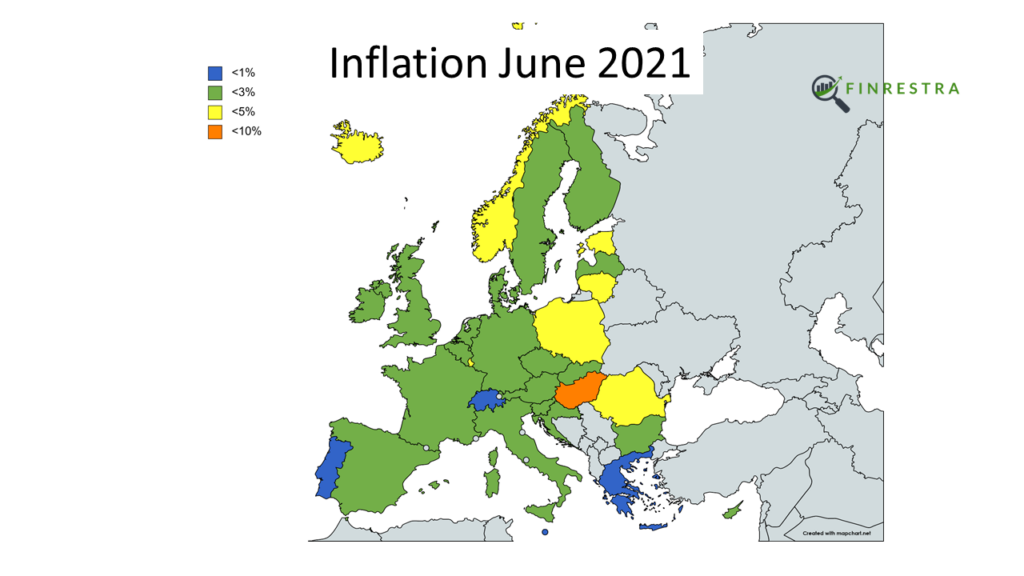

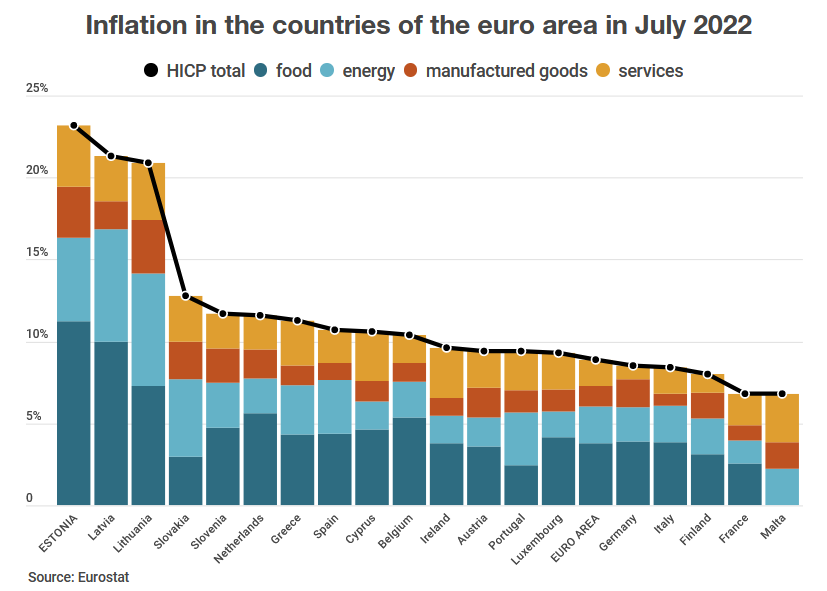

In June 2021, inflation was still close to 2%. In August 2022, it was above 10% in the European Union (EU) as a whole. But that number hides a remarkable divergence between countries. In Estonia, inflation reached a stunning 25% in August 2022. In France, it was 6.6%. In Switzerland, not an EU member state, inflation was just 3.3%.

A year before, in June 2021, inflation was very close to 2% in most European countries. With 5.3%, Hungary had the highest inflation. Inflation was lowest in Portugal, at -0.6%.

In this post, we’ll look at the change of inflation in 31 countries: the 27 member states of the EU, and the United Kingdom (UK), Norway, Switzerland and Iceland.

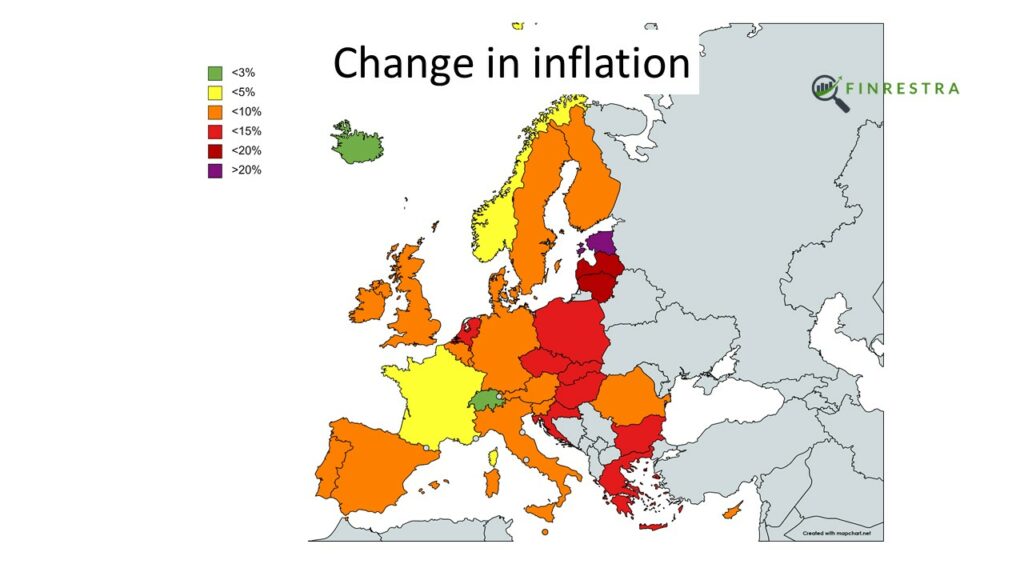

How can we explain the dramatic, uneven rise in inflation?

Energy intensity

Consumers are paying a lot more for energy than they used to. Companies also face higher energy bills, which has an impact on the price of their goods and services.

But energy prices are set on international markets, e.g. for oil, gas, coal and electricity. Why doesn’t expensive energy result in a similar rise of inflation across Europe?

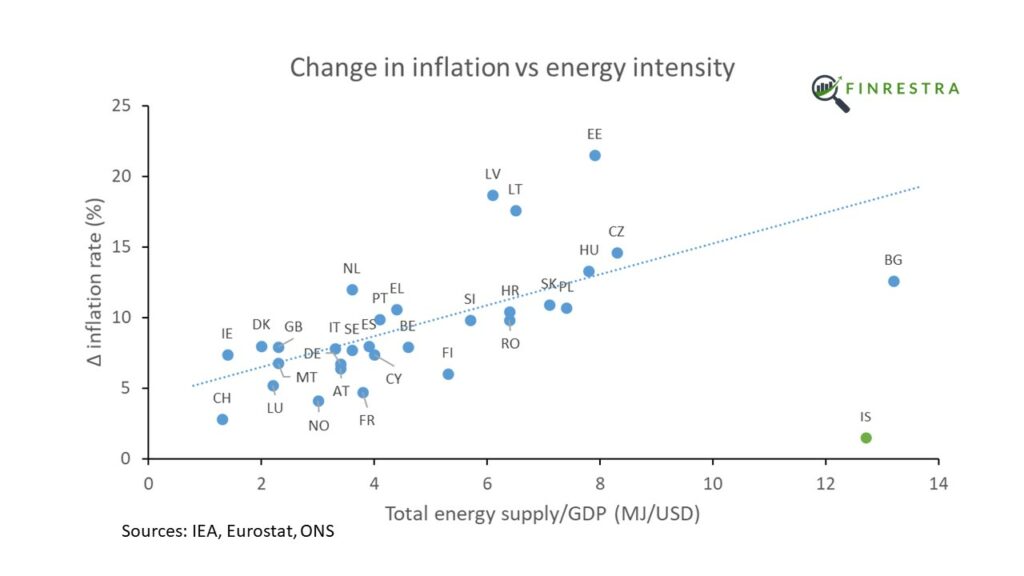

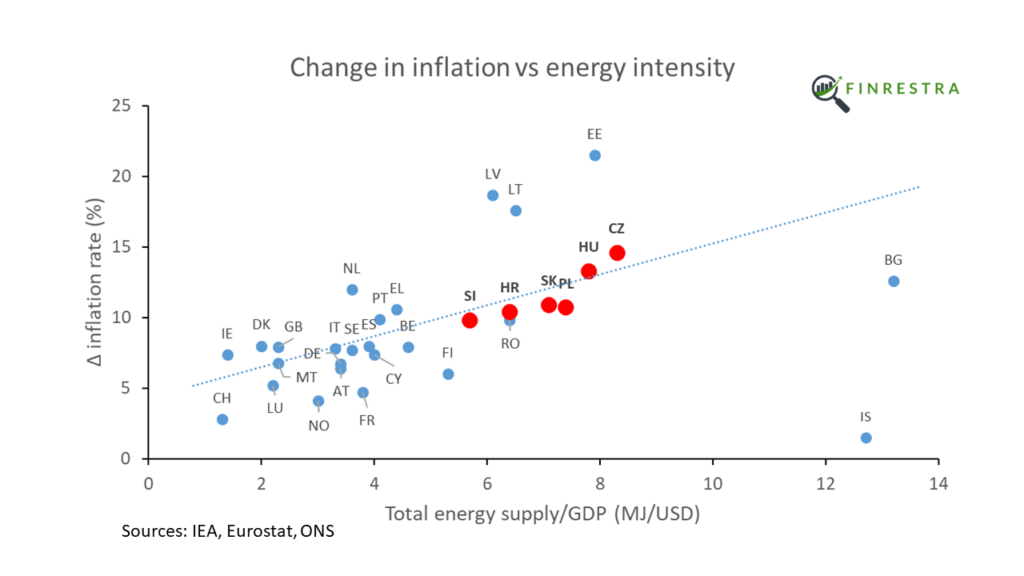

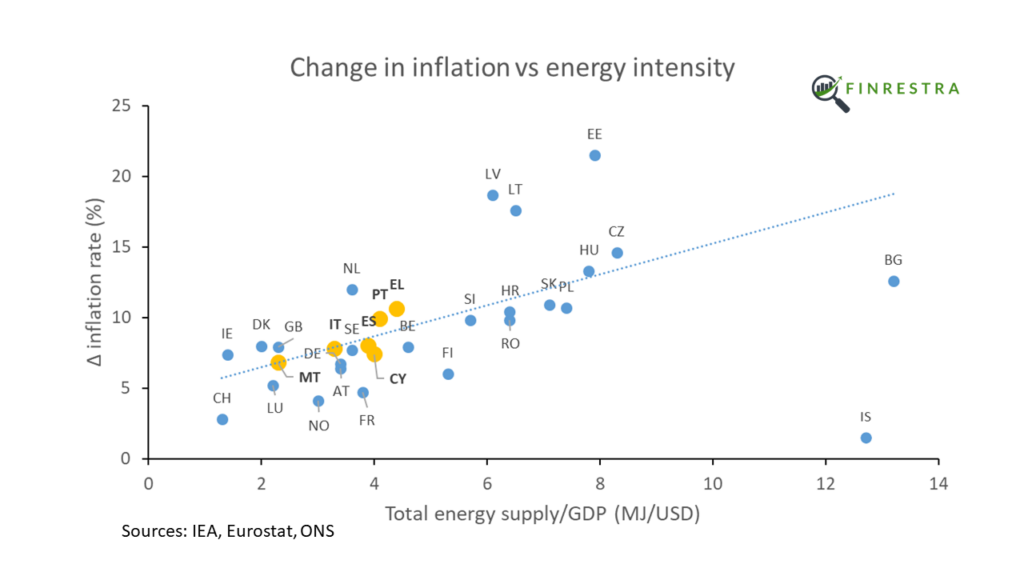

As the following figure shows, there is a strong correlation1 between the rise of inflation and the ratio of energy use to GDP2. As a general rule, the more energy a country needs to produce a dollar of economic output, the higher its inflation. Countries in Central and Eastern Europe have higher energy intensities and higher inflation rates than their Western European neighbors.

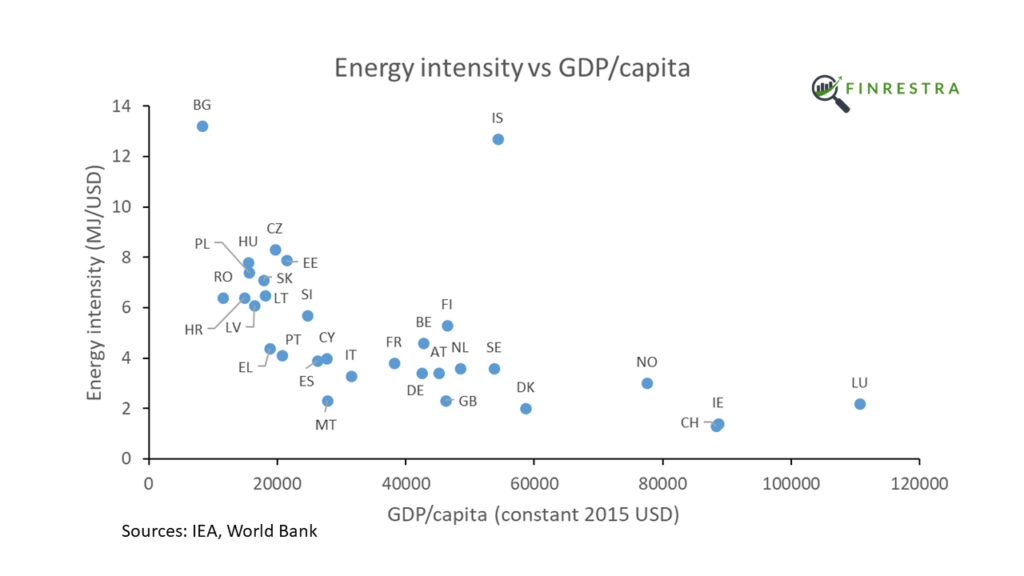

Countries with a lower GDP per capita tend to be more energy intensive.

So it’s not surprising that Central and Eastern European countries, who are relatively poor, are experiencing higher inflation than the West3.

But it’s not just an East-West story. Even within regions with similar GDP per capita, the more energy intensive countries experience higher inflation. For example Central Europe4,

Southern Europe5,

and the Baltics6.

The picture is less clear in Western Europe. The energy intensity of Luxembourg and Ireland is distorted by the denominator (small countries with a very high GDP per capita due to the presence of international companies). France already limited energy prices in 2021. The Nordic countries are just weird ¯_(ツ)_/¯

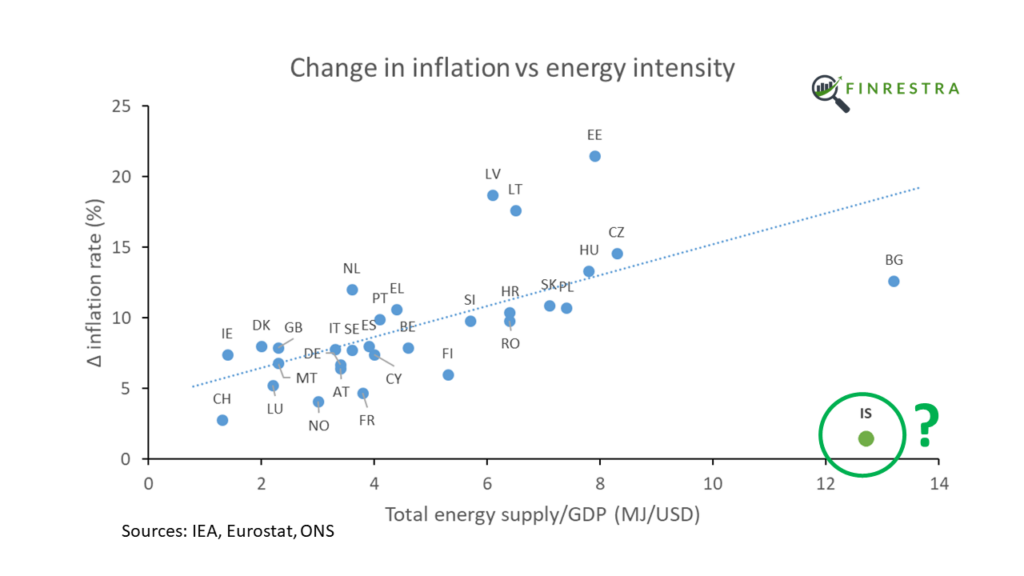

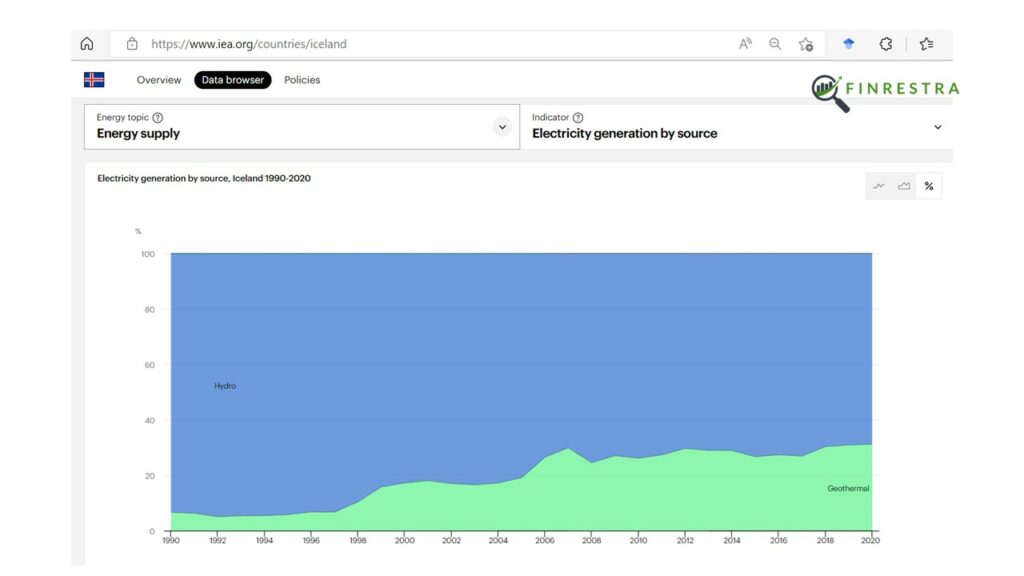

What’s going on in Iceland? Iceland is a rich country with an abnormally high energy use. Why doesn’t this result in much higher inflation?

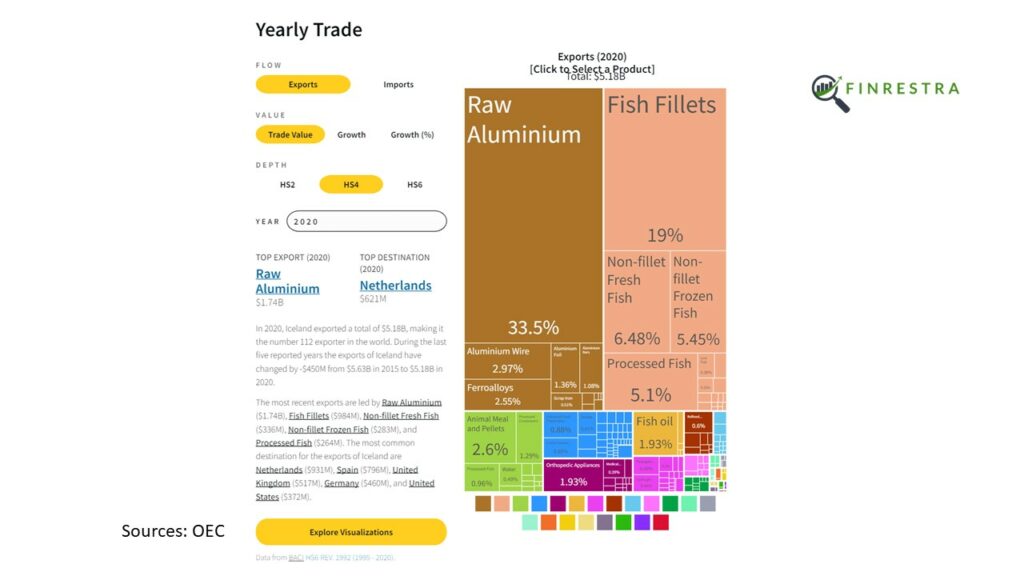

Although Iceland is a small nation, it’s a big producer of aluminum.

Making aluminum requires a lot of electricity. But all of Iceland’s electricity is generated from renewable sources.

So the Icelandic economy is less affected by higher fossil fuel prices than the rest of Europe. Fossil-free electricity also seems to be the explanation for the very low inflation in Switzerland.

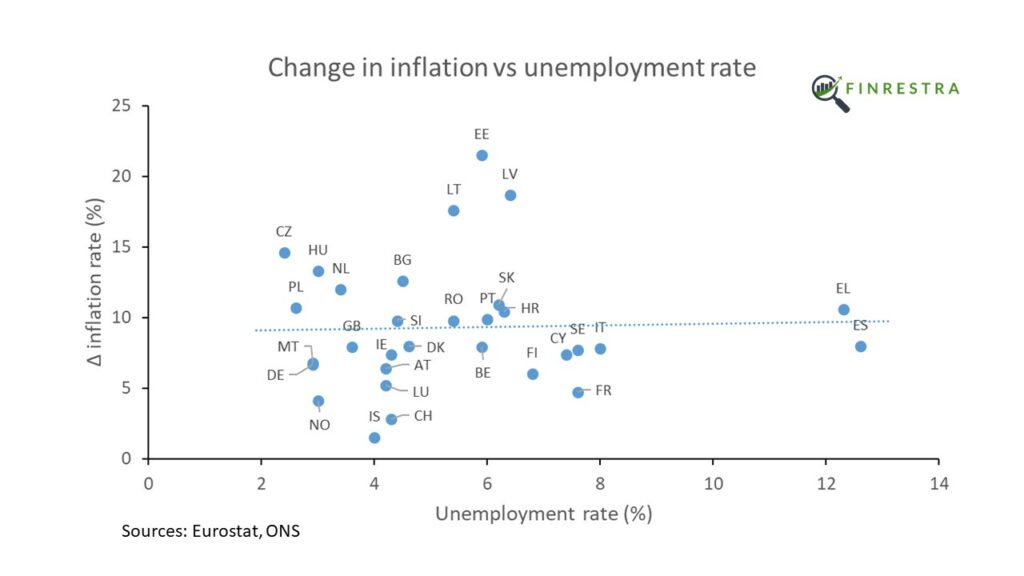

Unemployment

What other factors could contribute to the rise of inflation?

According to economic theory (NAIRU, Phillips curve), when unemployment is “too low”, workers demand higher wages. And higher wages lead to higher prices.

However, there is no correlation7 between unemployment8 and the change of inflation in Europe.

Inflation rose more in Spain and Greece than it did in Germany, although the German unemployment rate is much lower.

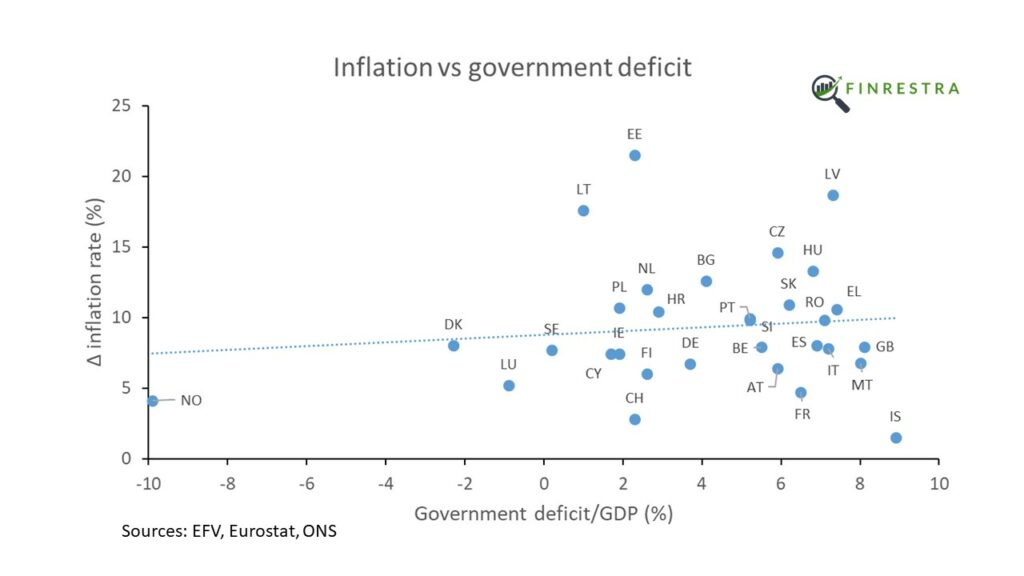

Government deficits and debt

Do deficits cause inflation (Fiscal theory of the price level)? It makes intuitive sense that if the government spends more money into the economy than it takes away with taxes, this deficit leads to inflation.

However, there is no correlation9 between government deficits10 and the rise in inflation.

Denmark and the UK have the same change in inflation, although the Danish government ran a budget surplus in 2021, while the British had an 8.1% deficit. Finland and Estonia had similar deficits, but their inflation numbers are very different.

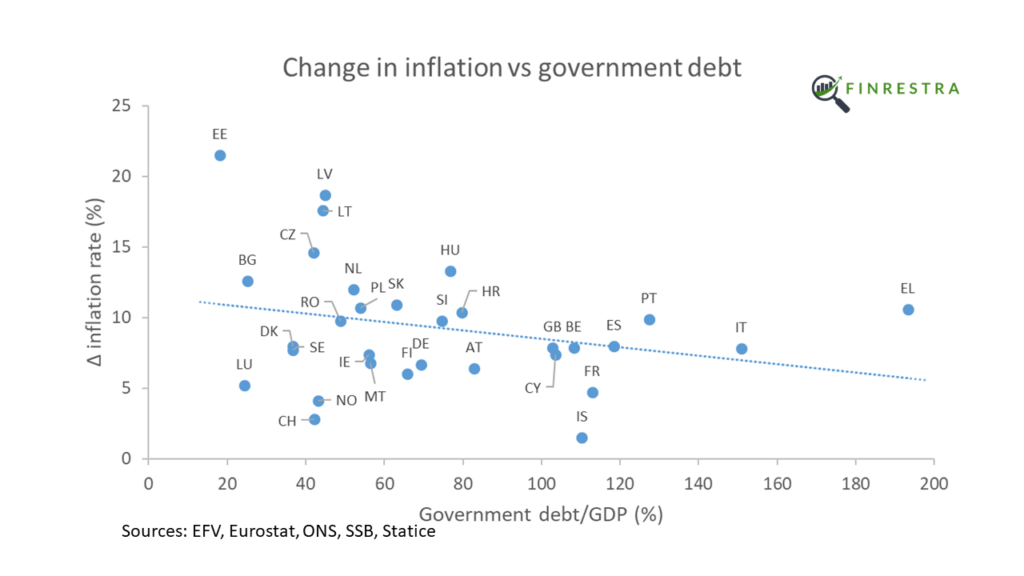

What about public debt? Maybe inflation goes up because people lose confidence in the sustainability of the debt. Or because governments choose to inflate away the debt.

However, there is a slightly negative relation11 between government debt and inflation12.

Greece, with its massive government debt, has experienced a smaller rise in inflation than the Baltic countries, where government debt is very low. Estonia has both the lowest government debt to GDP, and the highest inflation in Europe! Inflation is higher in the Netherlands than it is in Italy, although Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio is almost 100 percentage points higher.

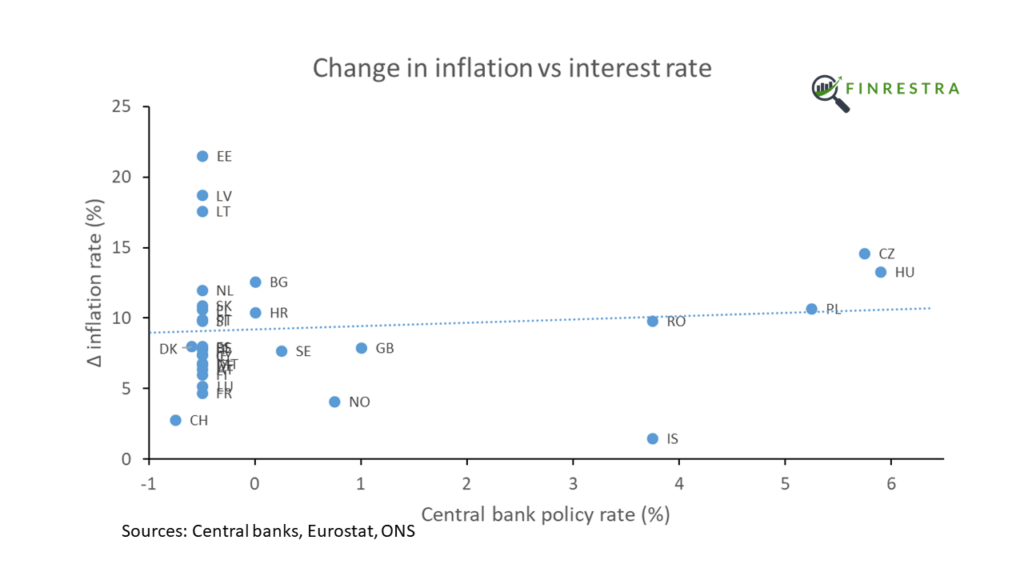

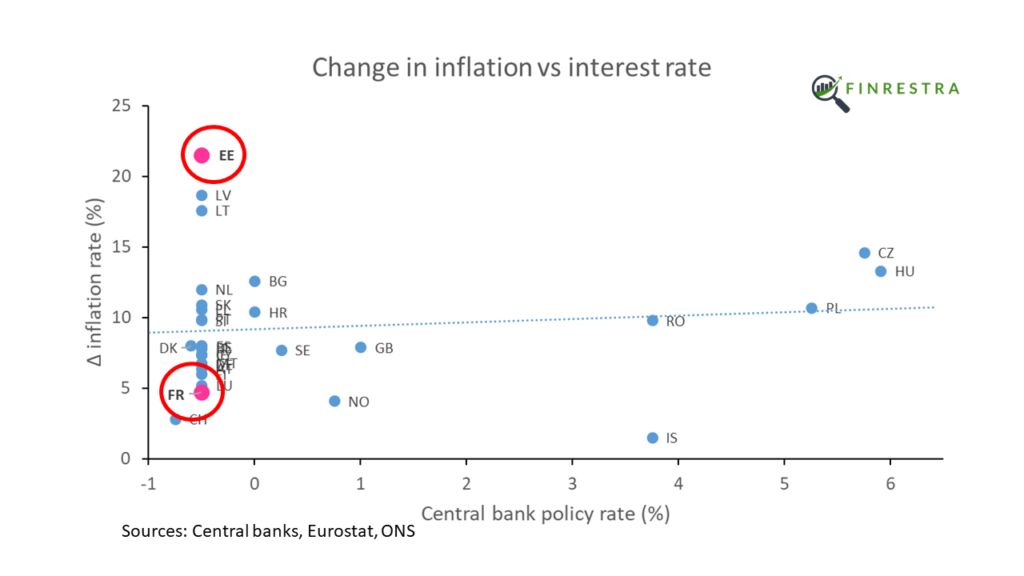

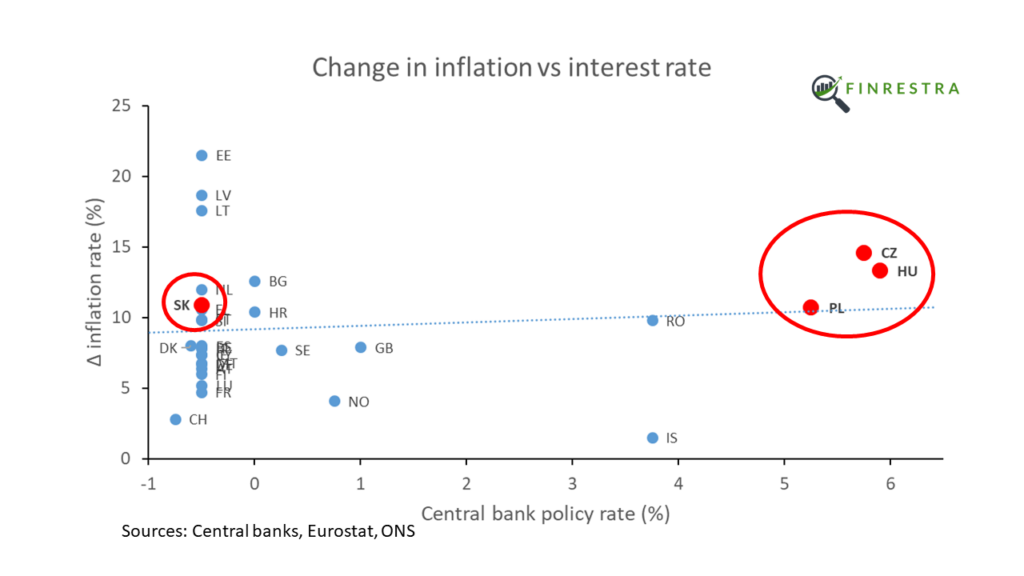

Central bank interest rates

Central bankers try to control inflation by changing interest rates. By influencing how expensive it is to borrow money, they influence prices of goods and services.

The picture shows central bank policy rates13 on June 1, 2022. Since that time, central banks have raised interest rates in an attempt to tamp down inflation.

But it’s not clear that interest rates have an effect on Europe’s inflation. In the euro area, where the ECB sets monetary policy for all 19 member states, inflation rose by 4.7% in France and 21.5% in Estonia.

In Slovakia, a country with a negative interest rate, the rise in inflation (+10.9%) is similar to neighboring Czech Republic (+14.6%), Hungary (+13.3%) and Poland (+10.7%), where policy rates were over 5%.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Europe’s worse inflation in generations is driven by energy. Conventional factors monitored by central banks don’t seem to play a role.

Contact

This work started as a small project I did during the summer, using June 2022 inflation instead of the change of inflation (see tweet below). In this post and in the video, I used the latest available data. I also added six countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Malta, Romania14 and Iceland) to the dataset.

If you have any questions or suggestions about this work, you can find me on Twitter @janmusschoot or mail me at jan.musschoot@finrestra.com.

For my professional services, please contact me on Linkedin or mail me at jan.musschoot@finrestra.com.

Statistical robustness

Twitter user Rasmus checked the data points I posted in June. His test shows that the regression line slope is different from zero:

Some further thoughts about energy prices

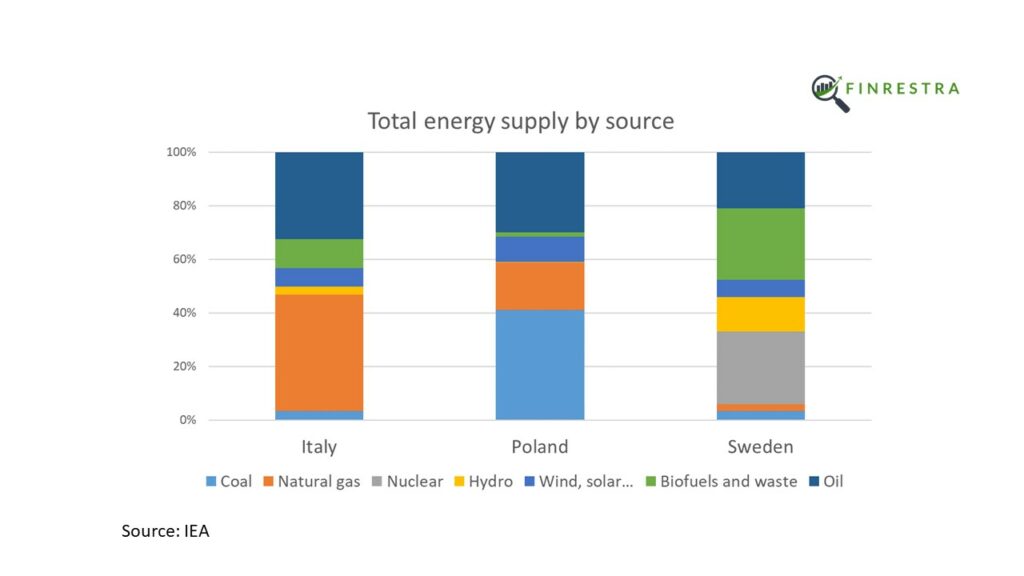

It is remarkable that there is such a strong correlation between inflation and energy intensity, given the different energy mix between countries. For example, natural gas is the most important fuel in Italy. Poland mostly burns coal, while Sweden relies on wood. While natural gas and coal prices are up hundreds of percent, that’s not the case for oil or nuclear.

I suspect the strong relation is due to electricity prices, which are often determined by the price of natural gas.

Other complicating factors that my analysis doesn’t take into account are price caps for energy (e.g. France), and the energy intensity of exporting industries (which should have less of an effect on domestic consumer price inflation).

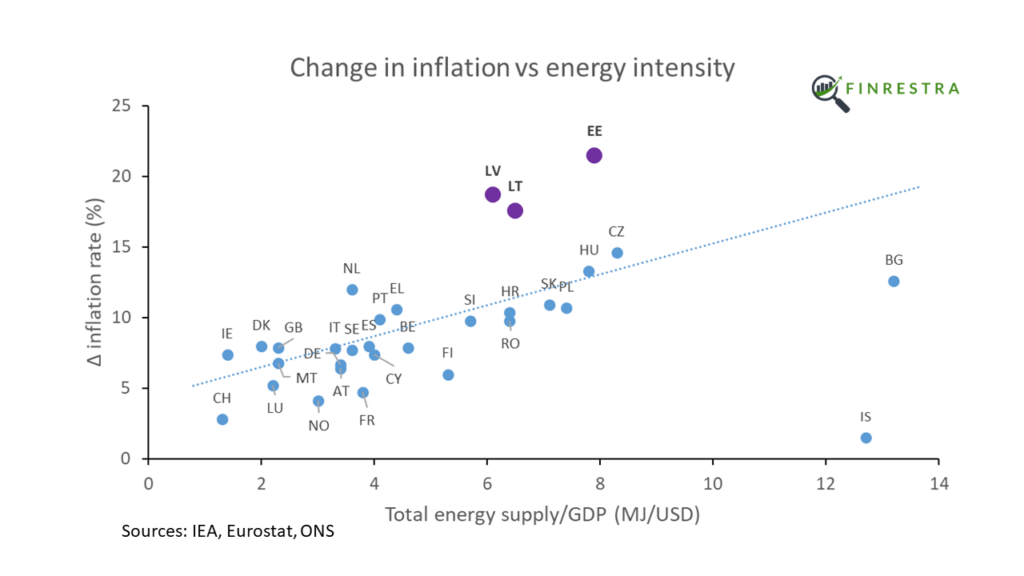

What’s the deal with the Baltics?

The three Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) are outliers. Their inflation is much higher than we’d expect based on their energy intensity. It’s not obvious that the fact that they share a border with Russia is the explanation. Finland, a euro country like the Baltics, also borders on Russia and has a relatively low inflation.

According to the central bank of Estonia:

There are several reasons why inflation is higher in the Baltic states than the average in the euro area. The share of energy goods in the purchasing basket of consumers in the Baltic states is larger, which has affected the rise in the price of the consumer basket. Natural gas and electricity were a little cheaper in the region before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but prices have now caught up to those in other countries.15

Useful energy-related links:

Energy statistics – an overview (Eurostat)

From where do we import energy? (Eurostat)

European natural gas imports (Bruegel)

Carbon intensity electricity (Electricity maps)

Electricity prices (euenergy.live)

Real-time electricity tracker (IEA)

National policies to shield consumers from rising energy prices (Bruegel)

Energy, inflation, and the impotence of the European Central Bank

This is the blog version of episode 12 of The Finrestra podcast: “What can the ECB do when inflation is driven by energy costs? Three proposals” (listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or YouTube).

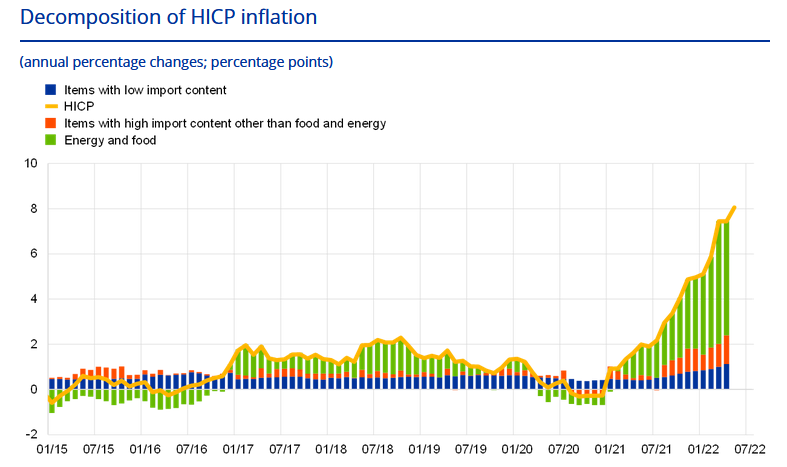

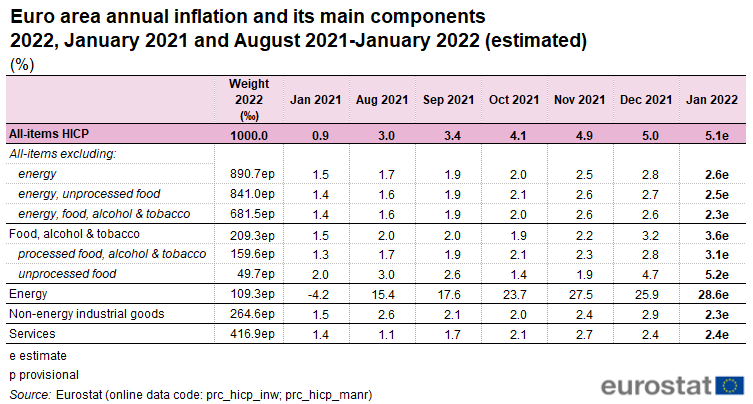

Euro area inflation was estimated at 5.1% in January 2022. That’s mainly due to energy costs. Furthermore, businesses will try to pass on their higher costs (transport, heating, materials) to consumers.

According to Isabel Schnabel, “Monetary policy cannot reduce the price of oil or gas.“

I disagree, as I told the ECB back in 2020. If instead of government bonds, the ECB had bought a controlling stake in oil & gas majors, it could force them to lower prices.

That’s probably too radical for conservative central bankers.

But there are other, more conventional paths.

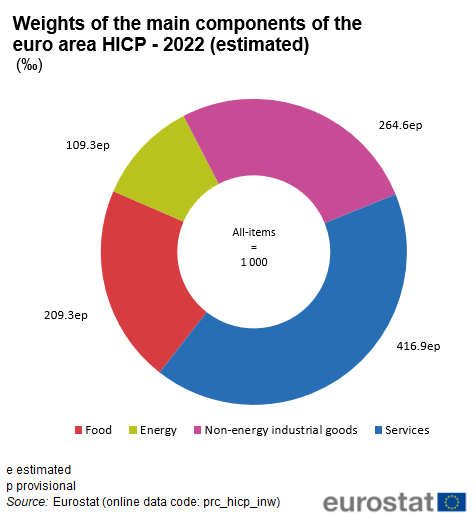

Energy makes up about 11% of Eurostat’s basket of harmonized index of consumer prices.

What if that percentage was lower? Volatile (fossil) energy prices would have less of an effect on inflation. This would make the ECB’s job easier.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that the ECB interferes with how Eurostat measures inflation.

Rather, the central bank could reduce our dependence on (fossil) energy.

How? Years ago, in 2017, I wrote a proposal for green investments in Europe. A European Green Infrastructure Company (EGIC) would install solar panels, build energy-efficient schools, networks of charging stations for electric vehicles… All of this infrastructure would be funded by the ECB. Why? It’s hard to imagine now, but we’ve had years were inflation was too low, i.e. below the target of the ECB. In my proposal, the EGIC would build in countries with low inflation and high unemployment. In case of the economy is overheating, new projects would be put on hold, so real resources like workers, machines and building materials can be used elsewhere in the economy.

If the EU had done this, there would be an abundance of renewable energy. This would price fossil fuels out of the market, making international energy prices almost irrelevant for European inflation.

Of course, in the real world EU politicians and central bankers have wasted the opportunity of low inflation and low interest rates.

But it’s never too late. Even without a European Green Infrastructure Company, the ECB can reduce the weight of (fossil) energy in consumers’ expenditure. High energy prices make it attractive to make buildings more energy efficient. In fact, central bankers like Isabel Schnabel have argued that the slow transition to a carbon-neutral economy is a market failure (see also this video).

The ECB could correct this market failure by making loans for energy-efficiency cheaper, for example by charging a negative rate of -5%. Banks would pass this on homeowners and landlords. At the same time, the ECB could raise rates on other loans. This would stimulate investments in building improvements, and reduce the demand for consumer loans. Companies would respond by increasing the production of building materials. It would also alleviate the labor shortage, because workers would be attracted by higher wages in the renovation business relative to other jobs.

Further reading:

The ECB can help fix the energy price crisis: Play the long game

Are higher interest rates going to crash the economy? A quick calculation suggests no

Even with inflation at 5%, some people believe that higher interest rates will crash the economy. Is this 2011 all over again1?

As I explained on Twitter, increases in debt servicing costs are small compared to rises of other production costs (e.g. labor). So if the economy does crash after rate hikes, it must be because of some other/indirect cause.

Banking on YouTube

I’m trying something new. I’ve started making videos about banking, monetary policy and sustainable finance.

I’m still trying to figure out the best format. But I already like the ability to use graphs and pictures. Compared to blogging, video is less nuanced. For example, you can’t link to all sources. But maybe that’s an advantage.

Here’s the first one, let me know what you think!

Is climate change the job of central banks?

Background literature:

- Conny Olovsson (Riksbank) argues that “monetary policy does not have the appropriate tools for counteracting global warming, but global fiscal policy is significantly better suited for this purpose.”

- Isabel Schnabel (ECB) argues that climate risks are mispriced by financial markets. Central banks should not sustain market failures.

- The fraction of bonds issued by carbon intensive companies in the ECB’s CSPP portfolio and accepted as collateral is far larger than the GVA of these companies, see e.g. Matikainen (figure 3) or Dafermos (figure 4).

- Paris Agreement, Article 2, 1(c): This Agreement, in enhancing the implementation of the Convention, including its objective, aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty, including by: Making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.

- The European Green Deal is a priority of the European Commission.

- Lagarde has said climate change is the job of the ECB: “[w]hether climate change (…) is to be considered as part of our primary objective. And the answer is yes.” (1:44)

- A green mandate for the ECB? Dirk Schoenmaker says yes, Hans Peter Grüner says no.

The financial risks of climate change: the case of France

A first assessment by the Banque de France.

CBDC

Some literature on central bank digital currencies (CBDCs).

- Short introduction by the Fed

- CBDC and privacy

- CBDC tracker has an overview of all projects and their status

- Another CBDC tracker

- CBDC platforms and tech partners

- Fabio Panetta (ECB) on retail payments and a digital euro

Central bank mandates

In their paper Against amnesia: re-imagining central banking, Benjamin Braun and Leah Downey describe the elite consensus on central banking as a ‘holy trinity’. This holy trinity consists of (1) an independent central bank that (2) sets the short term interest rate to (3) achieve stable prices1.

The fact that quantitative easing (QE) is still often called unconventional monetary policy speaks volumes for how deeply the holy trinity is ingrained in the minds of the community. However, more and more people are questioning this model of central banking2.

Central bankers are almost begging politicians to spend more. A formal framework for fiscal and monetary coordination would do away with the fiction3 of central bank independence.

There’s an explosion of ideas for new instruments, from yield curve control to canceling debt to green TLTROs.

While almost nobody wants to ditch price stability, central bankers are taking on extra responsabilities based on local sensitivities. European central bankers (both at the ECB and the Bank of England) are making their institutions climate friendly. The Federal Reserve has had a dual mandate of price stability and full employment for a long time. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand will take house prices into account.

Although central banking post-holy trinity will have its own challenges, I, for one, welcome our central bank overlords.

Links spring 2021

- Money laundering in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- The era of central bank convergence is over

- How can the ECB unleash building renovations

- Policy comes first, economic theory follows (JW Mason on Biden’s American Rescue Plan)

- The Jersey Way

- CLOs in Dublin

- Primer on money-laundering (Bribe, Swindle or Steal podcast)

- Corruption in the U.S. 7th fleet (Bribe, Swindle or Steal podcast)

- Tommaso Valletti on how the EU anti-monopoly system works in practice (On the role of economic consultants arguing in favor of M&A: “They produce a glossy pamphlet with three nice pages: exactly what the judge needs, he can say ‘ah, here is a counter-argument, here is an anecdote to rebut this. So, nobody knows’.”; On the capabilities of the EU: “DG Comp has less than 1000 people for half a billion citizens.”)

- Marbella, united nations of drug traffickers

- Alessia del Vasto and Rachel Oliver on their campaigns to change central banking: