Fiscal burden sharing poisons Europe

Who should pay for the corona crisis in the EU?

Philipp Heimberger discusses the possibility of a European recovery fund, funded by a common debt instrument.

On the Macro Musings podcast, Ashoka Mody says countries like Italy need fiscal transfers from other member states.

But fiscal burden sharing is a toxic idea, as Dutch finance minister Wopke Hoekstra demonstrated.

What’s the real problem?

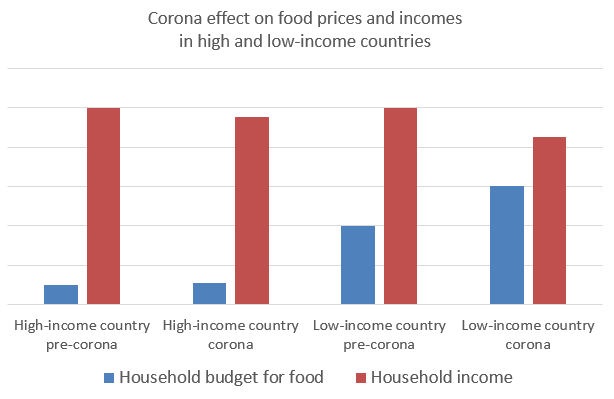

Italy is 135% of GDP. Spain and France are 100% of GDP, so three of the big Eurozone countries are not going to be able to do fiscal stimulus of 5, 7, 10% of GDP, which is basically what is going to be needed for this crisis. We’re going to need enormous amount of fiscal stimulus. Maybe Germany will do that. In the US, with this two trillion, they’re already at about 9% of GDP, and I expect that it will go up even more, for a number of reasons, but Italy cannot do anything close to that, or Spain cannot do anything close to that.

Ashoka Mody

Clearly, the problem is not the level of debt. The U.S. has a higher debt to GDP ratio than France and Spain.

The problem is the refusal of the ECB to close the sovereign spreads. As I write this, the German 10 year bond yield is -0.461. The Italian 10 year bond yield is 2.182.

How do we get out of this mess?

Every country should do whatever it takes to save its economy. Bail out businesses, pay unemployment benefits.

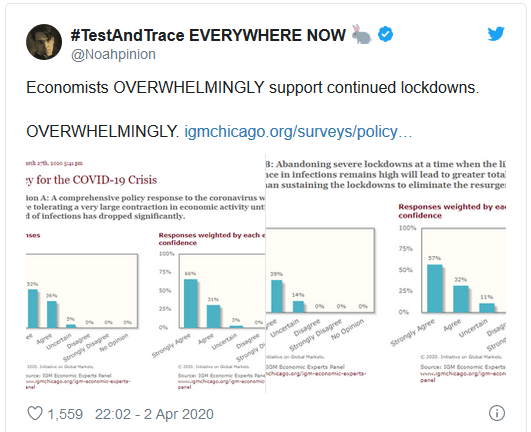

The expenditures can be funded by bonds. The ECB should keep the spreads low. That means buying whatever it takes.

Secondly, the ECB is once again neglecting its primary objective. Oil prices and unemployment point to low nominal aggregate demand. Without income support to households, it’s unclear how the ECB can achieve its inflation target.

So the ECB needs to do helicopter money drops, as suggested by Eric Lonergan, Frances Coppola, Positive Money Europe, and me.

But what does the ECB do? The Governing Council has never even discussed helicopter money, let alone planned to implement it!

This is not just incompetence, this is financial terrorism.

Frankfurt delenda est.