Central banks (CentBs) have drastically expanded their balance sheets in the wake of the global financial crisis. The Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB) followed the example of the Bank of Japan (BOJ) by buying trillions of dollars and euros worth of long-term bonds, a policy known as quantitative easing (QE).

The CentBs make these purchases by “base money”, i.e. cash and reserves1. Neglecting legal restrictions, CentBs can create base money at will.

There is a lot of controversy among economists about QE and its consequences for the balance sheets of central banks.

This post discusses the question of whether or not base money should be considered a liability of the central bank. After that issue is understood, we can clarify when the CentB can book a profit and how this affects government finances.

One of the stated goals of QE is to raise inflation. Some worry that once this happens, rising interest rates will cause massive losses to the central bank, resulting in unspecified “bad things”. I argue that these fears are unjustified.

Seigniorage: the profit from creating money

Monetary authorities have a monopoly on creating cash. I use cash in the sense of official physical money. Examples of cash are the €50 banknote in your wallet or (historically) coins like the Thaler. If anybody else attempts to make this official money without permission, they are guilty of counterfeiting.

How much richer is a central bank by coinage and printing money? It is not simply the value of the cash it creates, as it has to pay for the metals, paper, ink, tools, labor… it uses as inputs. The difference between the nominal value of the cash and the production costs is called seigniorage.

For rulers who have trouble collecting taxes, seigniorage is an easy way of generating income. When coins were made (partly) from silver or gold, the currency could be debased by lowering its noble metal content. Printing more (or higher denomination) banknotes is even easier. To protect the currency from irresponsible money creation by politicians, more-or-less2 independent central banks oversee the creation of base money. See this by the Banca d’Italia for a short introduction to seigniorage with some historical background.

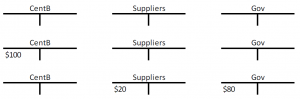

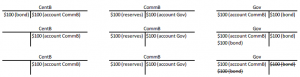

The profits from seigniorage belong to the state. Let’s say the central bank of a country prints a new currency. For convenience, the currency is labeled with the $-sign. Assume $100 is printed and the costs to the central bank are equal to $20. This $20 is paid to the suppliers of the CentB in return for their inputs. The $80 seigniorage profit can be paid as a dividend to the Treasury (which is part of the Government, Gov for short), as illustrated in the following picture:

Cash, reserves and “money”

Most people don’t hold much physical cash and prefer bank accounts instead. Similarly, commercial banks (ComBs) do not have vaults full of euro/dollar/pound… bills. They keep most of their base money in an account at the central bank3. The money commercial banks hold in accounts at the CB is called reserves.

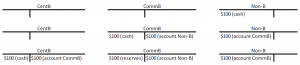

Suppose the agents in our example economy prefer electronic money to physical cash. Or that cash is outlawed, as some economists propose. What would happen to the cash ($100) in circulation? To trace that money when it is deposited at banks, we have to look at the balance sheets of the commercial4 banks, the central bank and the non-banking (non-B) economic agents (individuals, businesses, government agencies, non-profit organizations…):

There are some important aspects to highlight.

First of all, this example shows that the non-banking sector now no longer holds official cash. We are used to think that the cash in our wallet and the balance in our checking account are equivalent, but this is not true. Although both are used for payments, only the cash issued by the central bank is official money. Since the non-banking sector cannot open accounts at the central bank, bank deposits are strictly speaking not the same as cash.

Secondly, the commercial banks are not any richer by taking cash deposits. Their liabilities5 are equal in value to the asset the banks have acquired.

The non-banking sector has swapped its cash for a deposit at the commercial bank. The commercial bank has swapped the cash for a deposit at the central bank.

Thirdly, the central bank is not any richer either. It now has its physical cash back, and at the same time added a liability (the reserves), to indicate that CommB has $100. For commercial banks, cash and reserves are functionally the same thing. Both are official money, sanctioned by the central bank.

Fourth, note that the central bank can create as much official money as it pleases by making new reserves. The costs of seigniorage are zero in a cashless world. Instead of printing cash and giving it to the state, the central bank creates new reserves. The central bank then pays these new reserves to the government6. Commercial banks write the new reserves on their assets and match them with extra money in the government accounts on their liabilities. The government is richer, nothing changes in terms of profit/loss for the commercial bank.

Finally, this example shows how special central bank accounting is. Suppose there is a fire in a bank vault, destroying all cash (assume the cash is paper banknotes). This would be a disaster for a commercial bank, as can be seen in the middle of figure 2. This loss would cut into the capital7 of the CommB. When the depositors want to withdraw their money, CommB doesn’t have any assets to satisfy their request.

For the central bank, this wouldn’t be a problem. Commercial banks cannot ask anything “in return” for their reserves. If the central bank says reserves are official money, they are. Banks can settle payments between one another by changing the ownership of the central bank reserves.

In short: central bank liabilities (i.e. reserves) don’t need to be backed by assets. The central bank cannot go bankrupt.

Now, there is a very important caveat here. The discussion above assumes that monetary policy has not pegged the value of the currency to something else. Under a gold standard, people could swap cash for gold at the central bank. Some countries have pegged their currency to the US$ or (in the past) to the Deutschmark, promising a fixed exchange rate. When the central bank runs out of gold or foreign currency, it is unable to keep this promise.

Are reserves created during QE liabilities or seigniorage profits?

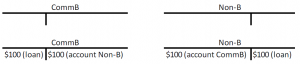

Commercial banks traditionally earn money from the interests on the credit they grant. When the bank lends money to a counterparty, it creates a liability (money in the account of the borrower) and it adds a loan8 on the asset side of its balance sheet. The balance sheet of the borrower shows the inverse situation. This mechanism is illustrated by figure 3. Note that this is how most bank deposits are created in practice. Deposits are mostly not created when people deposit official cash in a bank as in figure 2, but when the bank lends money.

At the end of the duration of the loan, the borrower has paid back the borrowed amount (called principal) plus interest9. The loan on the asset side of the bank is then erased, as is the liability of the borrower. Over the lifetime of the loan, the bank erases an amount equal to the principal plus interest from the bank account of the borrower. Because the total liabilities erased by the bank from its balance sheet exceed the assets it erased, the bank has earned interest from the borrower10.

What does this mean for QE and the profits for the central bank? There are two points of view in this debate.

The traditional view considers QE as similar to the deposit creation of commercial banks. The CenB acquires (existing) bonds from the private sector with newly created reserves. When the bonds are repaid, the bonds (asset of CentB) are erased together with the reserves (liability of CentB). The CentB makes an interest income. The interest received depends on the price it paid for the bonds11. The higher the price of a bond, the lower its effective interest rate.

An alternative view, which I’ll call the seigniorage QE view, is propagated by Marco Saba. In this line of thought, the reserves created for bond buying are considered to be seigniorage. The central bank earns not just the interest, but the principal of the bond as well. Instead of erasing the reserves as the bond is repaid, the central bank makes the reserves on its balance sheet permanent, as illustrated in figure 512. The proceeds are handed to the government.

Seigniorage QE enables the economy to deleverage (there is less debt), while the amount of bank deposits available for saving stays constant. The central bank provides assets (base money) with a fixed nominal value that are not related to credit creation by private banks. This gives risk averse investors a safe vehicle to save. Aggregate spending can keep on going while the economy as a whole saves13 money.

Whichever view you adhere to, figure 4 describes QE in both cases. The bond issuer (Non-B) is still obliged to pay his debt. The commercial bank (CommB) has only swapped an asset (a bond) for another one (reserves).

It is purely the accounting choice of the central bank that decides what happens next.

QE, interest rates, debt monetization and government finances

The above may seem a very academic discussion, but the opposite is true. Suppose the central bank buys government bonds under its QE program.

In the traditional QE view, the government saves interest payments to the private sector. The government pays interest on the bonds to the central bank, which pays this profit as a dividend to the government.

People blaming low interest rates on the central bank should realize this. Absent QE, high interest rates on the public debt would mean that the government needs to raise taxes or cut spending (for example on pensions) in order to pay interest to private bond holders.

In the seigniorage QE view, government debt is monetized, as illustrated in figure 6. The central bank pays a dividend to the government by transferring the government bonds it purchased during QE. The government now has a liability to pay off the bonds, but it also owns its own bonds. So it might as well scrap them. This has no impact on the balance sheets of the private sector.

Of course, market participants might change their behavior because they consider this to be an irresponsible policy. In response, people might spend more, less, or spend differently (e.g. by buying foreign currency, gold, guns, real estate…). That is a question which balance sheets alone cannot answer.

Debt monetization of the government bond portfolios currently held by their central banks would have a significant impact on government debt. For example, the ECB holds over 1 trillion euro in government bonds. This is more than 10% of total Eurozone government debt. The Fed owns about 2.5 trillion dollar of US Treasury securities (i.e. government bonds), one eighth of total US national debt. Of course, this policy would be a kind of helicopter money for the government, with all its associated political problems.

Inflation, monetary policy, losses and psychology

I hope this post has clarified some misconceptions and that it will stimulate further thinking. Not everything – especially debt monetization – might be legal under current central bank mandates. However, as I said before in another context, laws can be changed. So it’s never a bad idea to think things through before you’re in an acute crisis.

As this article is already very long, I will discuss the ways in which the central bank can try to control inflation/deflation in a later post. For example, when the debt is monetized, the central bank can no longer sell government bonds to “absorb” reserves. I also haven’t written about the possibility to pay interest on reserves.

There is however something I want to address before closing.

Some analysts worry about rising rates, and what they would do to the balance sheet of the central bank. Wouldn’t higher rates result in massive losses for the central bank?

It should be clear that this question is irrelevant. The central bank cannot be forced to sell its bonds. And even if the bonds lose paper value, so what? The central bank cannot go broke like a regular company14.

The obsession over central bank losses probably stems from an uneasiness over the fact that money can be created out of nothing. People15 might have a subconscious feeling that something has to back the currency, either gold or foreign currency. Creating money out of nothing, without taxation, feels wrong. Or they have an intuition that high government debts should be “punished” by high rates, the Japanese widow-maker trade notwithstanding. Or that debt monetization inevitably will spiral out of control. These concerns are all psychological.

Central bankers likely know all of this, and consider debt monetization a taboo to put pressure on politicians to force “reforms”. But there is no financial reason why extra seigniorage/public money/helicopter money cannot be done, especially at a time of slow growth and very low inflation.

===

I’m glad you made it through this long post. If you want to learn more about (central) banks, you should read my book Bankers are people, too: How finance works.

- Reserves are money that commercial banks hold in an account at the central bank. Read the full article for more details.

- No central banker is truly free from political influence.

- The central bank of the euro zone is the ECB. The central bank of the “US$ zone” (i.e. the USA) is the Fed.

- I.e. all banks but the central bank

- Liabilities are written on the right hand side of the balance sheet represented by the T-figures.

- As long as nobody outside the central bank owns the reserves as an asset, these central bank liabilities/reserves are rather meaningless. This would be similar to the central bank printing new bank notes and keeping them in a vault.

- To keep the figures as minimal as possible, I don’t draw the capital buffer banks have.

- Or another credit instrument like a bond.

- I don’t consider the possibility of a default by the borrower here.

- I have explained this in detail and with drawings before in my earlier post on QE. Start at the sentence “The fourth way for the RB to get rid of the money in the CB, is when the bond issuer pays the money back” and the picture below it.

- Again, I assume there are no defaults.

- For ease of the argument, the example uses a bond with an interest of 0%.

- Saving in the sense of agents who spend less than their income (=hoard money) and others who pay down debt.

- Again assuming that the central bank has not committed itself to defending something it doesn’t fully control, like an FX rate or the price of gold.

- I don’t want to mock anybody here, as I also believed these things before studying them in detail.