A global currency means global power for the Fed: How U.S. sanctions depend on the Federal Reserve

Russian exports invoiced in euro rather than dollar

Delusional talk from the ECB: Unleashing the euro’s untapped potential at global level

A global currency means global power for the Fed: How U.S. sanctions depend on the Federal Reserve

Russian exports invoiced in euro rather than dollar

Delusional talk from the ECB: Unleashing the euro’s untapped potential at global level

What do crypto enthousiasts have in common with defenders of independent central banks?

Based on the “Buy Bitcoin”-replies to ECB/Fed tweets, it seems the answer is “not much”.

However, that’s incorrect. Both groups think that their projects are apolitical.

Many central bankers view themselves as technocrats, divorced from politics.

But that’s a fantasy.

You see, anything a central bank does – even within its mandate – has political consequences.

Should monetary policy take into account climate change?

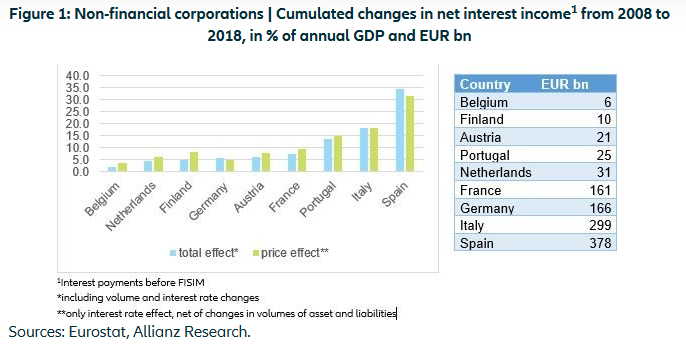

Should the central bank change interest rates or do QE to reach its inflation goal? Whatever option is chosen, monetary policy has distributional effects. For example, the German government has saved hundreds of billions in interest costs.

These two dilemmas illustrate that central banking is inherently political.

Therefore, economists should calculate the consequences of different monetary policy options. These scenarios will make the politics of the central bank’s actions explicit. For example, I estimated the effect of deeply negative interest rates (a proposal of Miles Kimball) on banks, governments, the ECB and the private sector.

Especially in the euro area, the ECB should take differences in asset mixes between countries into account.

Increased transparency will enable central bankers to defend monetary policy against criticism.

Update 26 January 2020: my arguments are obviously not new, see for example:

Economists are fond of analogies to describe technical ideas.

Most of those analogies are confusing and/or useless. As I wrote in the introduction of Bankers are people, too:

Economists and journalists writing for lay audiences tend to use metaphors when explaining financial concepts. For example: ‘Cheap credit is like heroin. It’s addictive, and the economy can overdose from it.’ That may sound nice, but what does it even mean?

This post explores the consequences of deeply negative interest rates set by the ECB, as proposed by professor Miles Kimball. It’s a shorter version of my previous post, plus an estimation of the economic stimulus of the proposal. Continue reading “Negative rates: a massive transfer from savers to bank shareholders and governments with little impact on economic growth. (Post in response to Miles Kimball)”

Or to be more precise, debate about the financial institutional framework edition.

How should banks be regulated? Ten years ago, this question would have only interested a few specialists. Discussions about bank supervision and the role of the central bank were way too boring for the general public1. Besides, bankers surely knew what they were doing?

The global financial crisis and its aftermath changed this complacent attitude. The existing rules did not prevent the worse financial crisis since the 1930s. Governments had to bail out banks at a moment’s notice. Politicians took drastic decisions during the panic of September 2008. While those actions were taken with little democratic oversight, national leaders2 were the only agents willing and able to stop the collapse.

The crisis spurred a thorough update of bank regulation. Both in the United States and in Europe, legislation was passed to make banks safer. Avoiding a repetition of ad-hoc bailouts became a priority. The U.S. got its Dodd-Frank Act. The European Union (EU) set up the European Banking Authority (EBA) and worked towards a banking union3. America and Europe implemented capital and liquidity standards based on the Basel III recommendations. Continue reading “What I like about America, finance edition”

In de nasleep van de financiële crisis hebben de centrale banken (CentB-en) hun balansen drastisch opgeblazen. De Federal Reserve (Fed) en de Europese Centrale Bank (ECB) volgden het voorbeeld van de Japanse centrale bank door voor biljoenen4 dollars en euro’s obligaties te kopen. Dit beleid wordt quantitative easing (QE) genoemd.

De centrale banken doen deze aankopen met de “monetaire basis”: cash en reserves5. Als we wettelijke beperkingen buiten beschouwing laten, kunnen centrale banken zoveel “basisgeld” maken als ze willen.

Economen zijn het niet eens over QE en de gevolgen ervan voor de balansen van de centrale banken.

Deze blogpost bespreekt de vraag als basisgeld bij het passief van de centrale bank gerekend moet worden. Nadat we dit onderwerp begrijpen, kunnen we verduidelijken wanneer de CentB winst boekt en hoe dit de financiën van de overheid beïnvloedt.

Eén van de doelen van QE is om de inflatie omhoog te krijgen. Sommigen maken zich zorgen dat de rente daardoor omhoog zal gaan, waardoor de centrale banken gigantische verliezen zullen lijden. Dat zou allerhande – niet verder gespecifieerde – rampen met zich meebrengen. Ik beargumenteer dat deze vrees onterecht is. Continue reading “Over de passiva en winsten van centrale banken”

Central banks (CentBs) have drastically expanded their balance sheets in the wake of the global financial crisis. The Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB) followed the example of the Bank of Japan (BOJ) by buying trillions of dollars and euros worth of long-term bonds, a policy known as quantitative easing (QE).

The CentBs make these purchases by “base money”, i.e. cash and reserves6. Neglecting legal restrictions, CentBs can create base money at will.

There is a lot of controversy among economists about QE and its consequences for the balance sheets of central banks.

This post discusses the question of whether or not base money should be considered a liability of the central bank. After that issue is understood, we can clarify when the CentB can book a profit and how this affects government finances.

One of the stated goals of QE is to raise inflation. Some worry that once this happens, rising interest rates will cause massive losses to the central bank, resulting in unspecified “bad things”. I argue that these fears are unjustified. Continue reading “Central bank liabilities and profits”