Eén van de populairste artikels op deze site legt uit hoe de Belgische personenbelasting berekend wordt. Door de taxshift zijn enkele details niet meer up-to-date. Dit is de nieuwe versie voor 2017. Ik heb de voorbeelden opnieuw doorgerekend en vergeleken met vorig jaar. Je zal zien dat de personenbelasting wel degelijk gedaald is.

Donderdag 13 juli is de deadline om je belastingen door te sturen via tax-on-web. De website heeft een knop waarmee je je belastingen kan laten berekenen.

Je kan dus laten voorspellen hoeveel je zal terugkrijgen of zal moeten bijbetalen van de belastingen.

Maar hoe werkt die berekening eigenlijk? Je krijgt een hele resem onbegrijpelijke sommen te zien, vol codes en onduidelijke ambtenarentaal zoals “om te slane belasting”.

Hieronder leg ik het simpelste voorbeeld uit: een alleenstaande zonder kinderen die heel het belastingjaar bij één werkgever werkte en geen andere inkomsten heeft dan zijn loon. Hij woont in Vlaanderen, vlakbij het werk, heeft geen huis en doet niet aan pensioensparen of andere zaken die recht geven op een belastingvermindering.

Wanneer je je loonbrief bekijkt, zie je dat er een (groot) verschil is tussen het brutoloon dat je werkgever betaalt, en het nettoloon dat op je rekening gestort wordt.

Er zijn twee belangrijke redenen waarom bruto en netto zo verschillend zijn: de RSZ en de personenbelasting. Van je brutoloon gaat 13,07% rechtstreeks naar de sociale zekerheid, de RSZ. Deze RSZ bijdrage telt niet mee voor de berekening van je inkomstenbelasting in Tax-on-web.

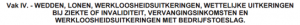

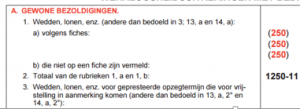

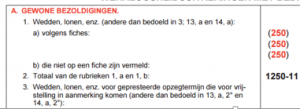

Het brutoloon (na aftrek van de RSZ-bijdrage) dat je verdiende in 2016 kan je vinden bij code 1250 van tax-on-web:

Continue reading “Hoe Tax-on-web je belastingen berekent in 2017”