Some interesting articles I came across recently:

Yemen has two governments (civil war), one currency, and two monetary systems.

IT project management horror story at German Apobank (in German).

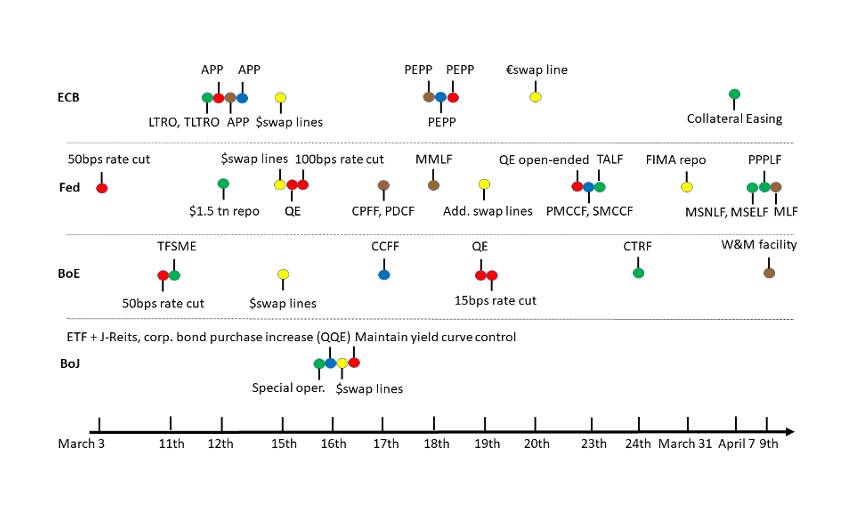

Overview of the Eurosystem response to the pandemic.

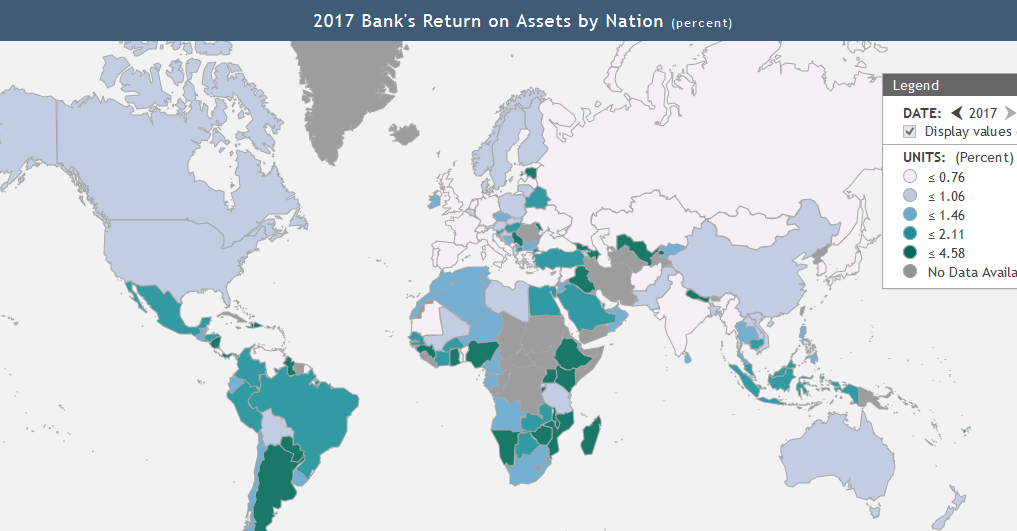

What central banks have done to help the economy survive Covid-19

Historical lessons from large increases in government debt

Euro area economic expansions are like Tolkien’s Elves: they don’t die of old age. The most recent one was murdered by corona.

(On a sidenote: I’ve been critical about the lack of blogging at the ECB. But it turns out that the Banque de France’s Eco Notepad is an excellent blog, as the four articles above show!)

All of the World’s Money and Markets in One Visualization

How may clicks to open a bank account? (Built for Mars on the user experience of retail banking)

The Economic Foundations of Industrial Policy: an amazing longread (very long!) on productivity, explaining why rich nations are rich

Ancient history: “In 2003, refinancing via LTROs amounts to 45 bln Euro which is about 20% of overall liquidity provided by the ECB.” (On June 18, 2020, banks borrowed 1.31 trillion euro from the ECB via TLTRO!)