Some websites I use to make YouTube videos

B-roll

AI images

Some websites I use to make YouTube videos

B-roll

AI images

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Finrestra Podcast! (Apple, Spotify, YouTube)

I am Jan Musschoot.

Warren Buffett once said: “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

And boy, have people been swimming naked in 2022!

Investors saw the valuations of tech companies crash by 50, 70 or even more than 90%.

The so-called “geopolitical” European Commission – who wants the EU to be the first climate neutral continent – had to beg for gas around the world after boycotting Russia.

But the naked swimmer that I want to focus on is the ECB, a favorite of this podcast.

This is what Lagarde said about inflation at the end of 2021:

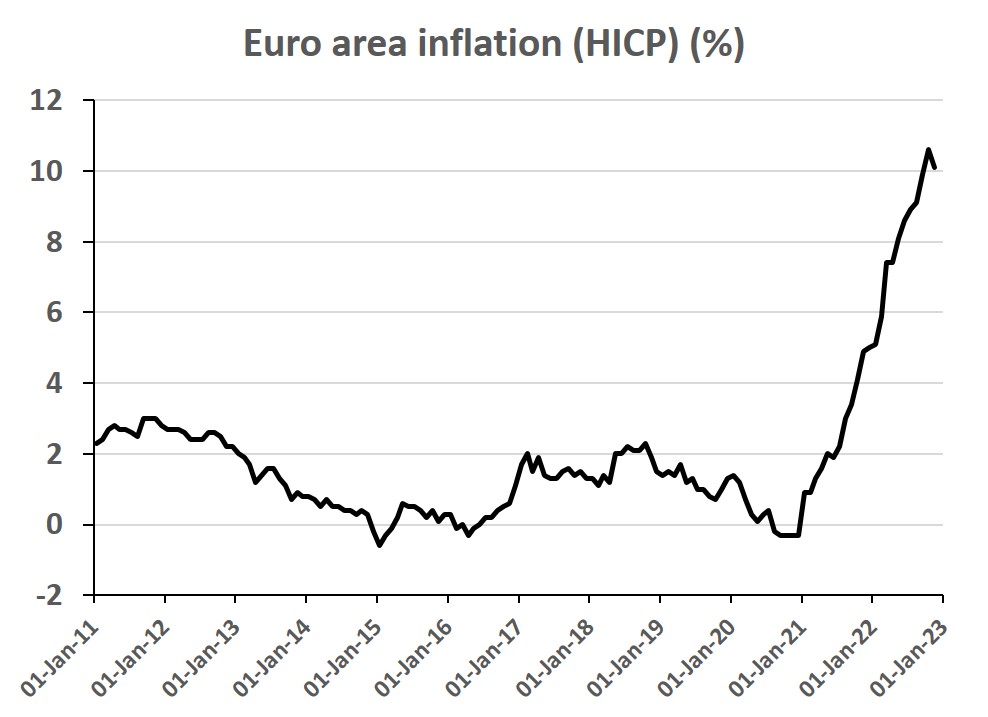

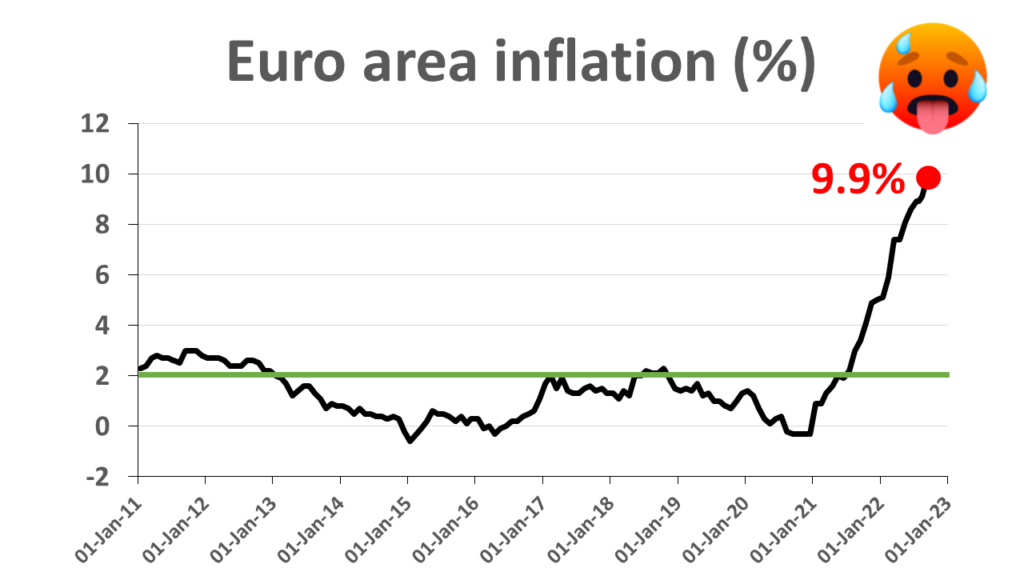

So inflation was supposed to have been a hump, gradually coming down to the 2 percent target over the course of 2022.

But in fact, inflation had been too high since the summer of 2021, and it basically kept on going up for the entirety of 2022. In December of 2022, it dropped a little, but it was still 9.2 percent according to Eurostat.

The ECB’s economists have been worried a lot about inflation expectations and wage-price spirals.

But what’s been driving Europe’s inflation for more than a year has been the cost of energy. It’s not clear at all how the metrics that central banks usually look at are relevant for this kind of inflation. I did some research last year that showed that if you look at government deficits, the unemployment rate, or the central bank interest rate, these are basically irrelevant when it comes to predicting the inflation that we observed.

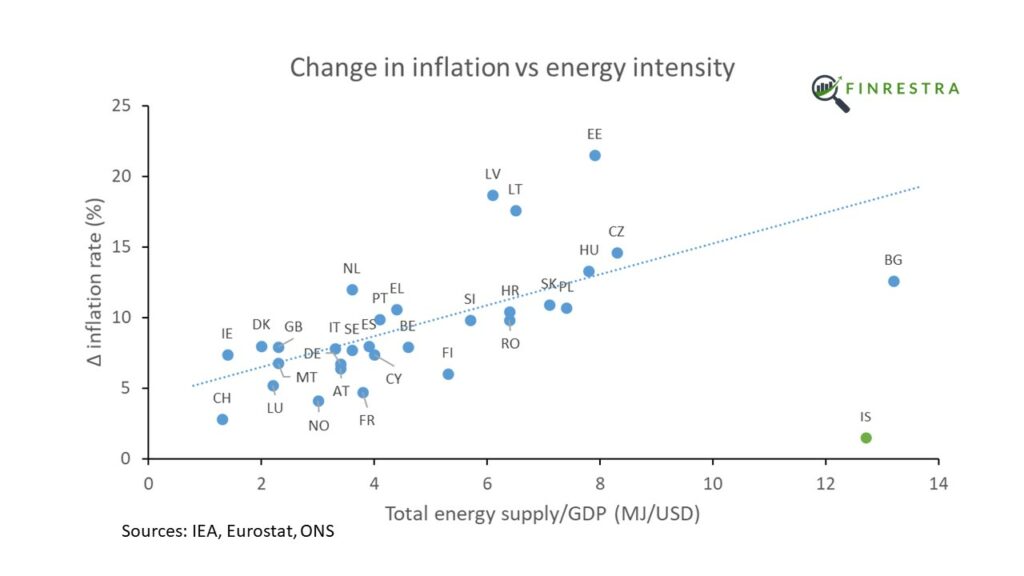

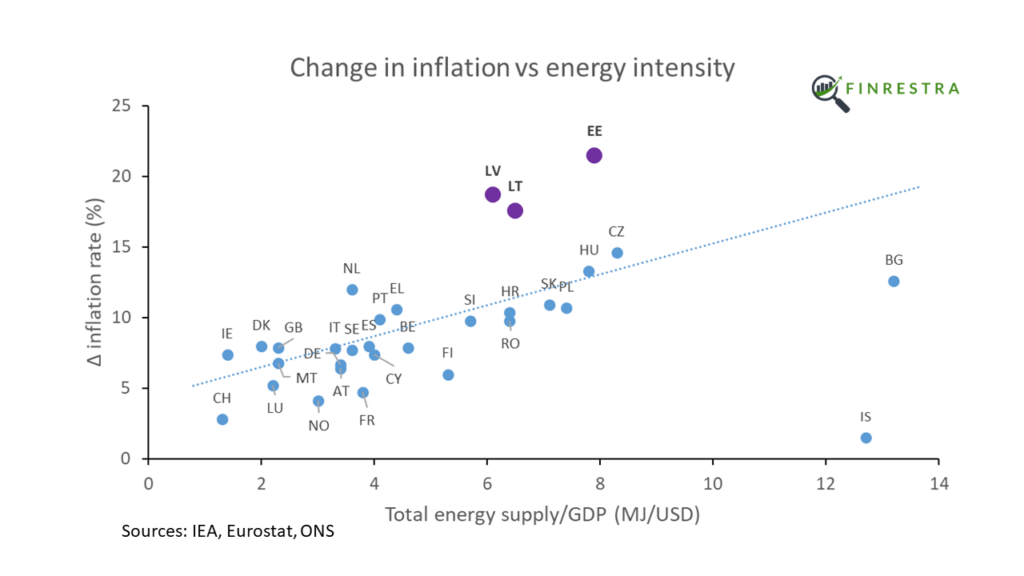

What’s mostly correlated to the current inflation is the amount of energy economies use relative to their size. In other words, energy intensity is what drives inflation.

And when it comes to energy, the ECB has screwed up. Yes, central bankers made a lot of speeches about climate change since Lagarde is in charge. But I can’t heat my home with speeches and tweets.

If the ECB had funded investments to make us less dependent on imported fossil fuels, inflation would have been much lower.

Imagine that the EU had invested massively in building renovation, heat pumps and clean energy sources while inflation was below target.

This would have reduced our vulnerability to Russia and other geopolitical rivals.

And fossil fuels would be a much smaller part of the consumer price index.

On top of that, Europe’s industry would have plenty of cheap energy right now…

So energy-driven inflation was the first tide that showed that the ECB was swimming naked.

Now on to the second tide.

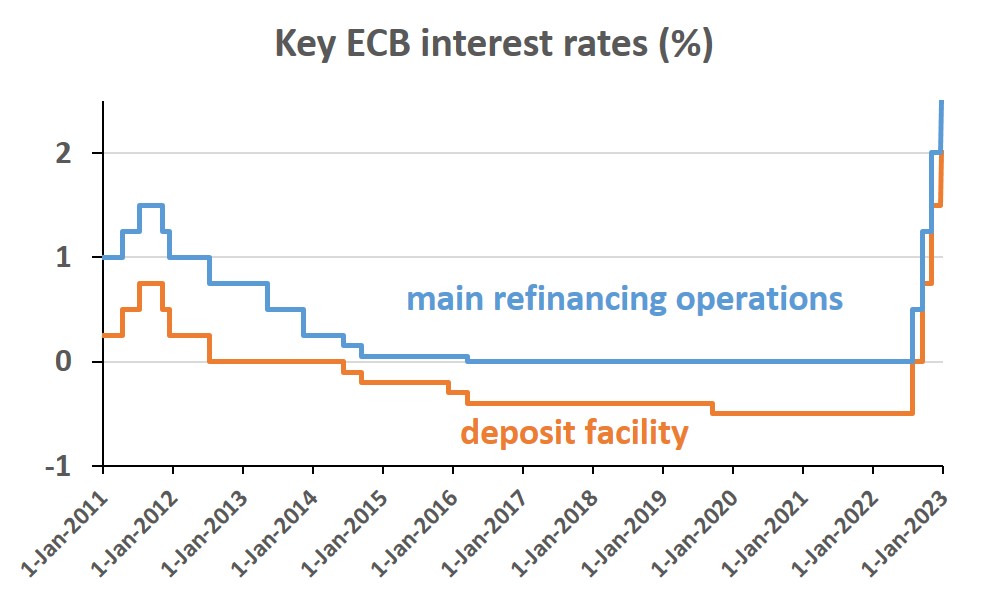

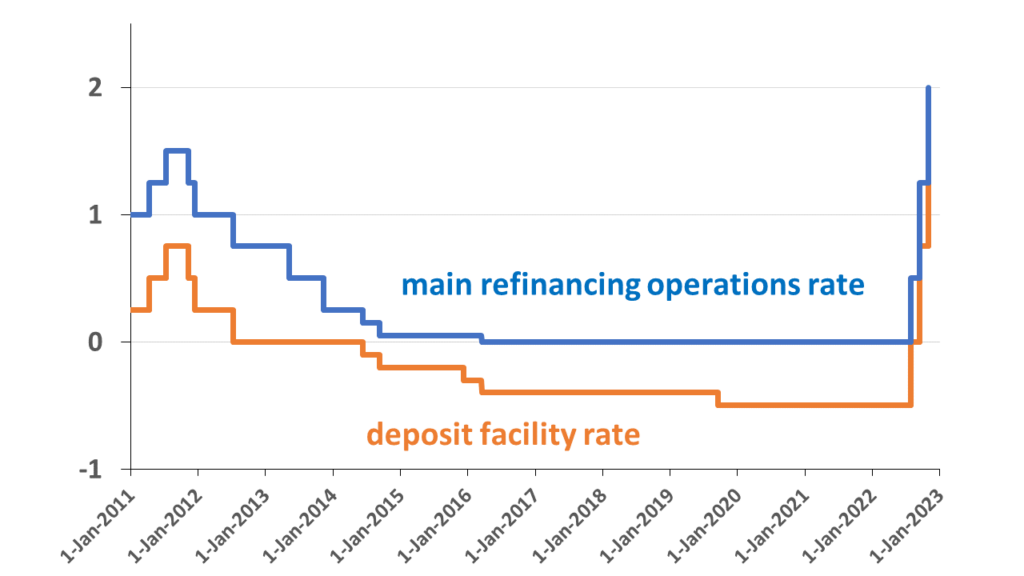

With inflation out of control, the ECB needed to do something. While Lagarde said in 2021 that it was unlikely they would raise rates in ‘22, the central bank has raised rates 4 times since the summer. The deposit facility rate went from negative 0.5 percent to positive 2 percent.

But this exposes the ECB to another problem, which is the mismatch between its assets and liabilities. While inflation was below target, the ECB bought trillions of euros of bonds. A lot of these have a fixed, negative yield. Under the PEPP, the pandemic emergency purchase program, the ECB put a turbo on this QE.

And how were these bond purchases funded? With bank deposits.

Now what happens when interest rates go up? The central bank starts to pay interest on these bank deposits, while its assets have a fixed yield.

According to one estimate, the Eurosystem is going to lose about 600 billion euro because of this failing risk management.

Anyone with a basic grasp of finance could have predicted this.

I even told the ECB to issue bonds instead of funding their assets with reserves.

Of course, they didn’t listen, because they’re so smart…

And what’s extra sad, is that the ECB has been complaining that governments haven’t invested enough in infrastructure.

Central bankers also complain about how untargeted government relief to help citizens and companies with their energy bills contributes to inflation.

The problem is again that the ECB didn’t put its money where its mouth was.

For years, QE has kept government funding costs in check, without any conditions on how governments should spend to keep inflation in check.

Maybe as a serious, non-political central bank, the ECB should have actually made sure that these crucial investments got done?

Instead, the ECB basically acted as a financial speculator, counting on low inflation and low interest rates forever.

Again, just imagine that the ECB would have invested not in securities, but in real infrastructure over the past decade.

How much better off Europe would be right now!

The final tide that went out in 2022 is that of Lagarde’s leadership.

Everybody knows that she’s not an economist. So maybe we shouldn’t blame her for failing to anticipate the inflation or the financial losses.

But she was previously a minister in France and the head of the International Monetary Fund.

So she must be a strong leader, right?

For those of you who’ve been listening to the podcast for a while, you might remember what I wrote in my New Year’s letter to Lagarde a year ago.

I suggested that either she quit, or she starts doing her job.

Obviously she’s still the President, so she didn’t quit.

But as the President, she should have fired the people who’ve been feeding her false predictions for all of this time.

At the end of 2021, ECB staff projected that euro area inflation would be about 3% in 2022. And core inflation would be below 2%.

I don’t know if it’s even possible for Lagarde to fire the most high profile economists like Isabel Schnabel or Philip Lane. But you’d expect some heads to roll.

But we didn’t see that at all. What we did see, was ECB staff asking for higher wages, to keep up with inflation.

Irony is dead…

Now before I go, I want to thank everybody who has supported this podcast and my YouTube channel. It’s not always easy to combine this with my other work, but I do appreciate your feedback!

In the coming year, I’m planning to release one podcast episode per month. And I want to do about a dozen deep dives into central banking and the financial system on the Finrestra Youtube channel.

So if you want to keep informed, please subscribe!

This has been another episode of the Finrestra podcast.

You can follow me on Twitter @janmusschoot.

You can mail me at jan.musschoot@finrestra.com

Thanks for listening and till next time!

(P.S.: Lagarde cartoon created with Dream by Wombo)

The start of the new year is a good time to reflect on some things I did.

Last year, I wanted to get 150,000 views on YouTube.

Although I didn’t reach that target, I am quite pleased with the progress I made. Especially given that the first half of 2022 was so busy that I could hardly create any new videos.

So as of 8 January 2023, the Finrestra YouTube channel has 33,551 views and 247 subscribers.

Some videos did well, others didn’t get the number of views that I expected they would get. That’s life…

One of the features of YouTube is that your content can suddenly be picked up by the algorithm, even when it has been posted months earlier. For me, that a big advantage compared to social networks like Twitter and LinkedIn.

In 2023, I hope to be able to create about a dozen ‘deep dive’ videos, like the one on inflation and the one on interest rates.

In addition, I’d like to make a podcast episode every month (minus the summer holidays).

Rather than maximize the number of views, it would be great if I can get more watch time. Currently, my most popular video has been watched for 150 hours.

If I can create 10 videos that get watched 200 hours or more in 2023, I’ll be very happy 🙂

Thanks for your support!

This episode is available on Apple podcasts, Spotify and YouTube.

Transcript:

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Finrestra podcast! I am Jan Musschoot.

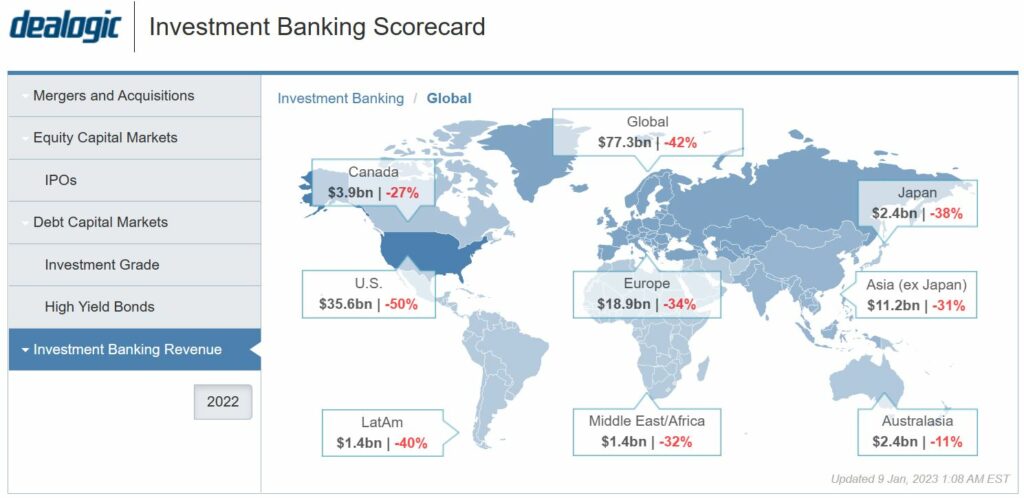

In this episode, I will talk about the sale of HSBC Canada and especially what HSBC can do with the cash it will receive from this sale. But first, let’s do a quick recap of the financial news of November.

FTX, a crypto trading platform, went bankrupt and its founder SBF went from being a multi-billionaire to essentially being broke.

In the euro area, inflation finally went down a little. Inflation was 10% in November whereas inflation was still 10.6 percent in October. Inflation is going down a little thanks to lower energy prices.

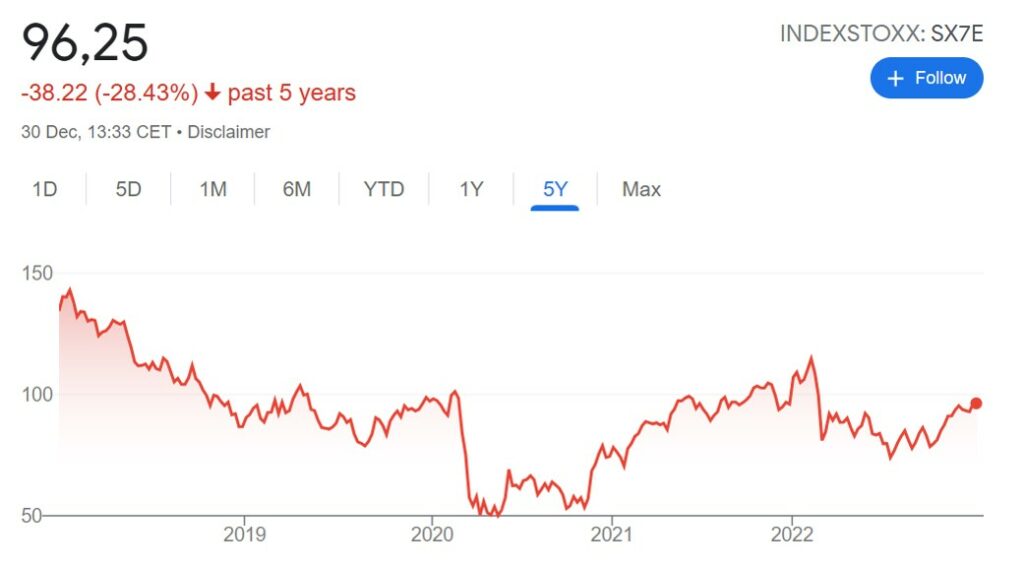

There was also news from two large European banks: Swiss Credit Suisse and Italian Monte dei Paschi di Siena both raised capital.

In other banking news – and also the topic of today’s episode – HSBC sold its Canadian subsidiary to Royal Bank of Canada (one of the largest Canadian banks). This fits into a broader pattern that I in one of the previous episodes of the Finrestra podcast called Go big or go home.

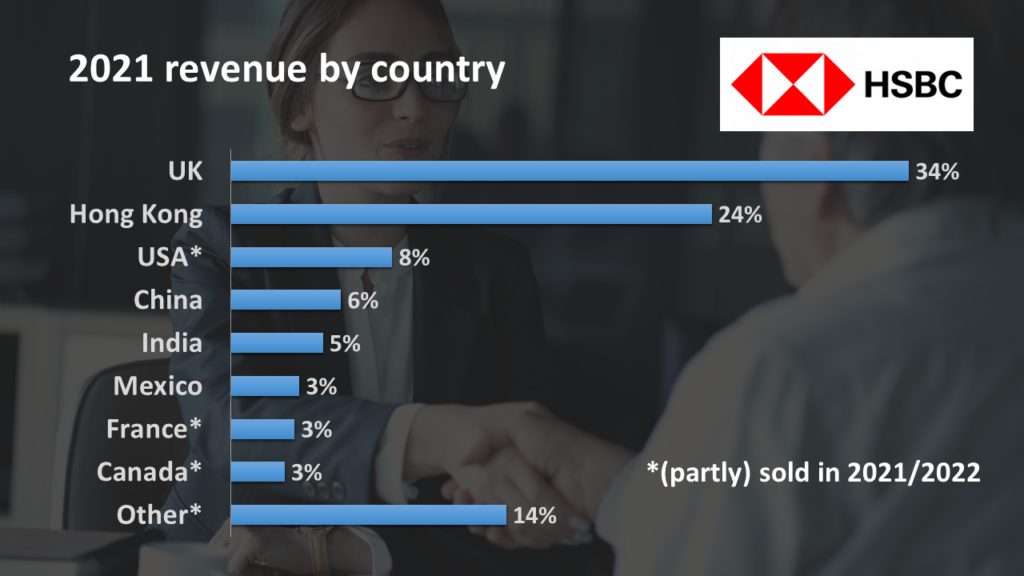

If you look at where HSBC derives its revenue from, Canada is barely three percent of revenue. It’s about four percent of profits and also four percent of the balance sheet. So banking in Canada is just a small part of the global group that is HSBC.

So it makes sense to exit this market, because you cannot have the scale you want to be highly profitable. Canada also has some big domestic banks who dominate banking in the country, so it makes sense for HSBC to exit the market, especially given that they received a good price for it.

This Go big or go home strategy is something that HSBC has been following for a few years now. For example, last year they also announced that they would exit [part of] the retail banking business in the US and that they would sell the French retail banking business, which was also about three percent of the group’s revenue. But they cannot compete to with the large French banks in France. And then in November 2022, so last month, HSBC also sold its bank in Oman (in the Middle East) to a local bank.

And this ‘let’s go big or go home’ strategy is not unique to HSBC. For instance last year I did a podcast episode about the sale of Bank of the West by BNP Paribas. The French multinational bank sold its US retail banking division to focus more on its core markets. And that’s also what HSBC has been doing here with the sale of HSBC Canada.

In financial terms, it seems that HSBC has done a pretty good deal because they received 13.5 billion Canadian dollars (which is about 10 billion US dollars). That’s about eight percent of HSBC group’s market cap. So that’s actually a good deal. If you look into the financial statements, they say they will make a net profit of more than 5 billion dollars on this sale above the book value1. And of course, selling the Canadian division will also shrink HSBC’s assets by a little less than 100 billion US dollars. So the sale provides a good boost to the capital ratio of HSBC as well.

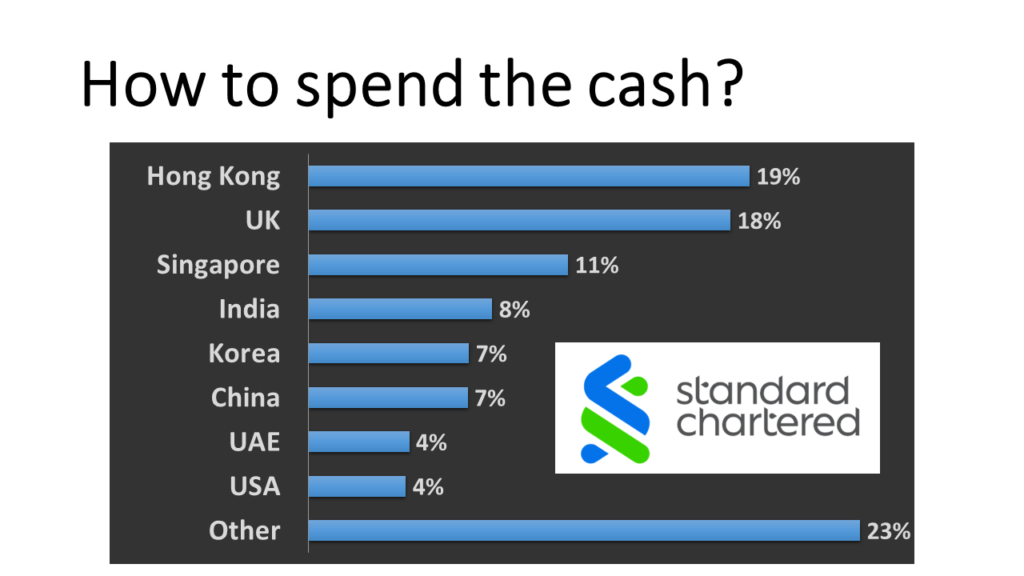

Now let’s focus on what HSBC could do with the cash that it will receive.

One possibility is just to return it to the shareholders in a dividend. But that’s kind of boring, so what I would do is to follow the Go big or go home strategy and ‘go big’ in the core markets of HSBC.

HSBC’s core markets are firstly in Asia, where it’s the biggest bank in Hong Kong and also has significant operations in China, India, in the Middle East, and in some other Asian countries.

So what could we do with the cash (or the cash plus some extra borrowed money)?

The obvious takeover candidate would be Standard Chartered. Standard Chartered is another British bank that is based in London and is mostly operational in the Far East (and also partly in Africa and the Middle East). If HSBC were to buy Standard Chartered, there would be synergies of course in the London offices. I’m not sure if they would be allowed to take over the Hong Kong division of Standard Chartered because maybe HSBC would become too dominant in Hong Kong, but at least buying the Asian divisions would be a huge boost to HSBC in Singapore and it would also strengthen the bank in China, India and South Korea. Also in the United Arab Emirates and Asian economies like Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam. All those countries would contribute to a higher market share of HSBC and hopefully also to higher profitability and economies of scale.

I already mentioned that they should probably sell the Hong Kong division of Standard Chartered. And I guess they should also sell the African subsidiaries of Standard Chartered because I don’t see a lot of synergies there. And HSBC is mostly focused on Asia and not on Africa. So that would also bring in some extra cash because the 10 billion US dollars won’t be enough to buy standard Charters. But I think there’s a very clear business case to purchase Standard Chartered.

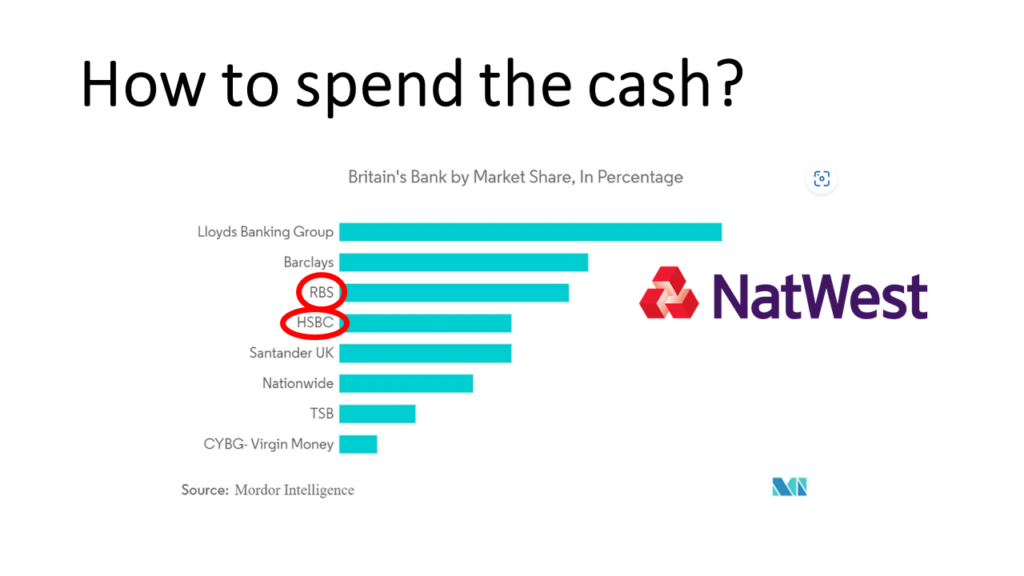

Another possibility would be to stay in the United Kingdom. So I found some research by Mordor Intelligence showing the market share of banks in the British market. You see that Lloyds is the clear market leader while HSBC is only the fourth largest retail bank in the UK (together with Santander UK). So a possible takeover target would be NatWest, which is the parent company above Royal Bank of Scotland – which is currently the third largest bank in Britain. Together with HSBC, they would be about as large as Lloyds Banking Group. So they would be the first or second largest bank in the United Kingdom. This [acquisition] would definitely provide some economies of scale on its British home market and would be quite easy to integrate. I think that deal makes a lot of sense also from a business perspective. Compared to Standard Chartered, where you would need to do a lot of divestments and integration in a lot of markets, the NatWest acquisition would be quite simple in terms of geography. You would also only need the approval of the British authorities. So I think that makes a lot of sense as well.

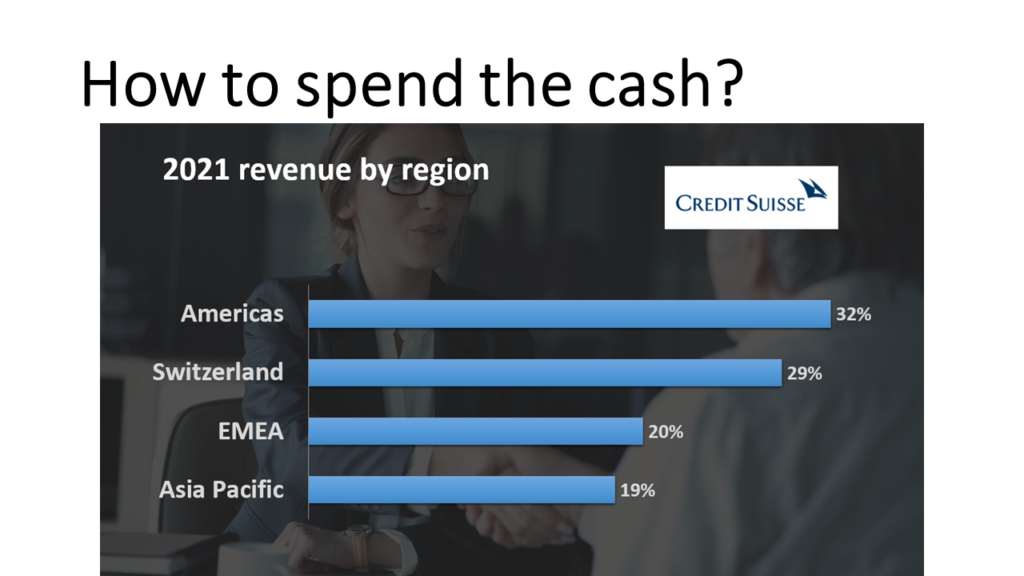

And then finally, thinking out of the box, we could also look at Credit Suisse. I wouldn’t suggest to buy the entirety of Credit Suisse, although its market cap is so low that with $10 billion you could almost buy the entire bank.

But what is probably a better idea is if HSBC would buy the Asia Pacific operations and maybe also the Middle Eastern operations of Credit Suisse. So I guess you don’t need the entire amount of 10 billion dollars. But by buying the Asia Pacific operations of Credit Suisse, HSBC could strengthen its wealth management in countries like China but also in Singapore and in other East Asian countries. And maybe also strengthen some of the investment banking operations in Asia. I think management of Credit Suisse would probably be happy to sell those divisions because then Credit Suisse can focus more on its core divisions in Switzerland and the Americas. While now CS are a global bank but they don’t have the size they need to be a real global bank.

So these have been three ideas. HSBC has sold its Canadian division for a lot of money. They could either buy Standard Chartered, or NatWest, or the Asian activities of Credit Suisse. I’m very curious of course what you think. Should they just return the money to their shareholders? Or should they buy other banks? Or do you have any other ideas? Maybe they should focus on share buybacks.

As always, you can reach me by mail at jan.musschoot@finrestra.com. Or you can find me on Twitter, I’m @janmusschoot or you can connect with me on LinkedIn.

This has been another episode of the Finrestra podcast. Thanks a lot for listening and till next time!

Background:

European inflation is driven by energy (intensity). Inflation falls as energy prices drop.

Credit Suisse profile

HSBC profile

Transcript with links to sources:

The European Central Bank is raising interest rates.

Here is ECB President Lagarde:

“The Governing Council decided today to raise the three key ECB interest rates by 75 basis points. […] The Governing Council also decided to change the terms and conditions of the third series of targeted long-term refinancing operations, known as TLTRO III.” (press release, video)

In this video, I’ll explain what it all means.

Why is the ECB raising interest rates?

The ECB is responsible for price stability in the euro area. It defines price stability as an annual inflation of two percent. But since the summer of 2021, inflation has exploded far above the two percent target. In September of 2022, inflation was 9.9 percent.

So what is the ECB doing about inflation?

The ECB has raised two2 key interest rates.

The ECB pays the deposit facility rate on money that banks have deposited at the ECB. That’s similar to the interest rate you receive on your savings account.

Banks can also borrow money from the ECB for a short period. These seven day loans are called “main refinancing operations” (MRO). The main refinancing operations rate is the interest rate that the ECB receives on these loans.

The ECB has increased the deposit facility rate and the main refinancing operations rate already three times in 2022.

Before these rate hikes, the deposit facility rate had been negative since 2014. And for previous rate hikes, we even have to go back to the year 2011. As of 2 November 2022, the deposit facility rate will be 1.5 percent and the main refinancing operations rate will be 2 percent.

How much money will the ECB pay to banks or receive from banks?

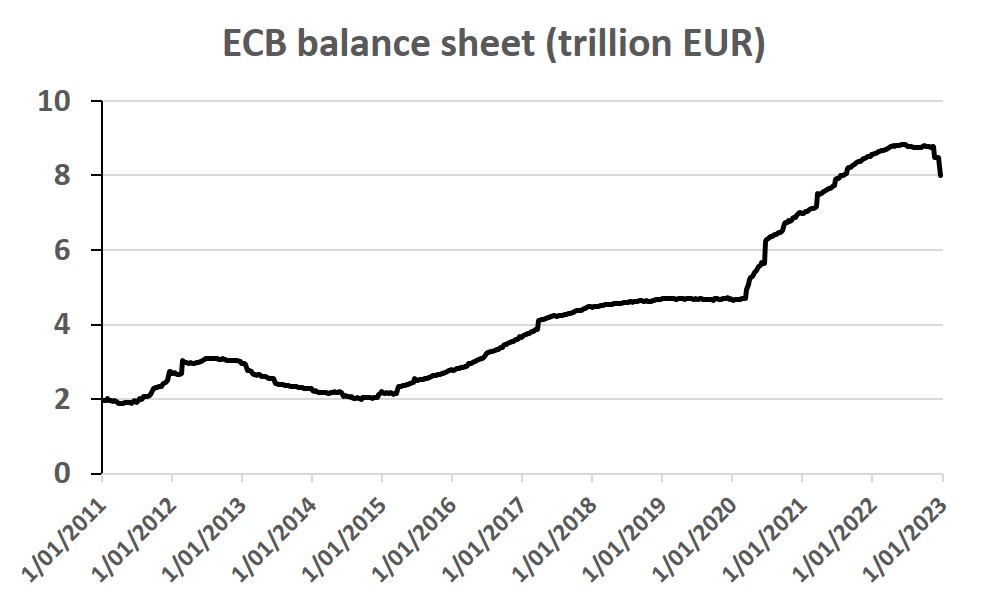

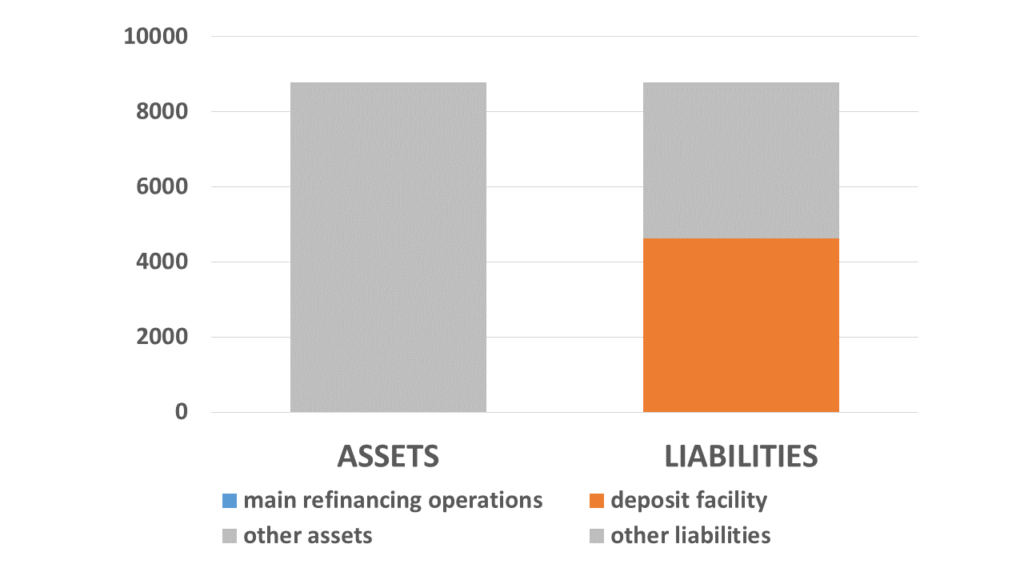

To answer that question, we need to look at the balance sheet of the ECB. The ECB has a balance sheet of almost 8.8 trillion euro (8,800 billion euro).

At 4.6 trillion euro, the deposits of banks in the deposit facility make up a little more than half of the ECB’s liabilities.

I didn’t forget to include the main refinancing operations, but these loans are less than 4 billion euro, so you cannot see them on the asset side of the balance sheet.

How much will the ECB pay to banks?

4.6 trillion deposits times a deposit facility rate of 1.5 percent means that the ECB will pay 69 billion euro to banks. The ECB will actually pay a little more, because banks also have something called “minimum reserves” at the ECB. And by the end of 2022, the ECB will also pay the deposit facility rate on these minimum reserves. Before [21 December 2022], it paid the main refinancing operations rate.

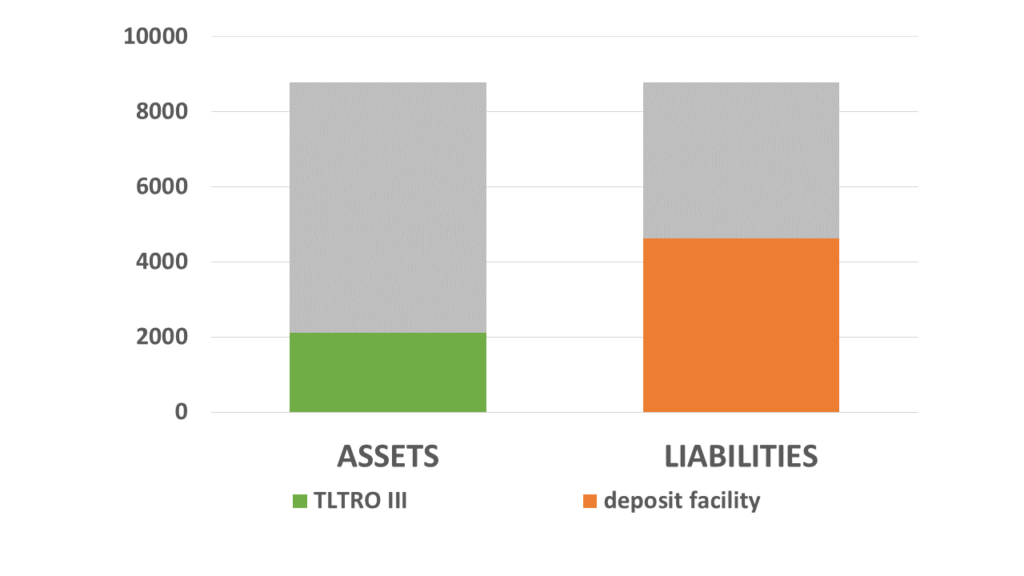

Lagarde: “The Governing Council also decided to change the terms and conditions of the third series of targeted long-term refinancing operations known as TLTRO III.”

So TLTRO III are three-year loans made by the ECB to commercial banks. The ECB offered these loans between the end of 2019 and the end of 2021. What was special about these three-year loans is that banks had to pay a negative interest rate to the ECB. So in fact they could borrow money from the ECB and pay back less than they had borrowed in the first place.

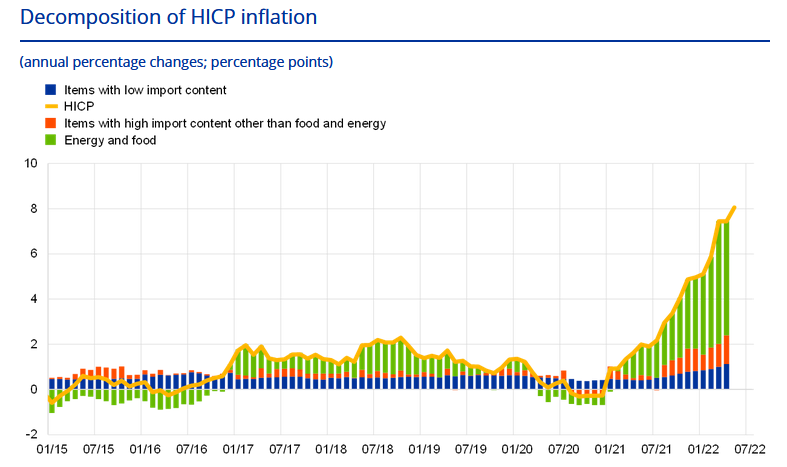

You can ask “why did the ECB do that?” Well, if you look at the inflation chart, you can see that at the time when the TLTRO loans were initiated, inflation was below the two percent target of the ECB. But now that inflation is far above the two percent target, the ECB has decided that these negative rates on the TLTRO loans are no longer justified.

And so they have decided to increase the interest rate for the remainder of the TLTRO period to the deposit facility rate. For banks that have outstanding TLTRO loans and also deposits in the deposit facility, the ECB has made it possible to repay the TLTRO III loans early4. This will have the effect that both the assets and the liabilities of the ECB go down, so this will shrink the balance sheet of the ECB.

To recap: the ECB has increased the main refinancing operations rate to 2% and the deposit facility rate to 1.50%. The ECB will pay the deposit facility rate on the deposits and minimum reserves of banks and it will receive the deposit facility rate on the TLTRO III loans of banks.

Taking into account the interest that the ECB pays on the deposit facility and the minimum reserves, and the interest it receives from the TLTRO loans, in one year the ECB should be paying 41 billion euro to banks at the current level of the deposit facility rate (1.5%).

If you are Christine Lagarde and you want to improve your communication, I suggest you read my book Bankers are people too, in which I explain how banks and central banks work using cartoons and also a lot of balance sheets but especially lots of stories about banks and central banks.

I have focused on the technical details of higher interest rates and the TLTRO loans, but of course since the ECB is

responsible for price stability, the question is: will higher rates actually help to reduce inflation?

I did an entire video on inflation in Europe (not just in the euro area, but also in countries with other central banks than the ECB) and to be honest, it doesn’t look very promising.

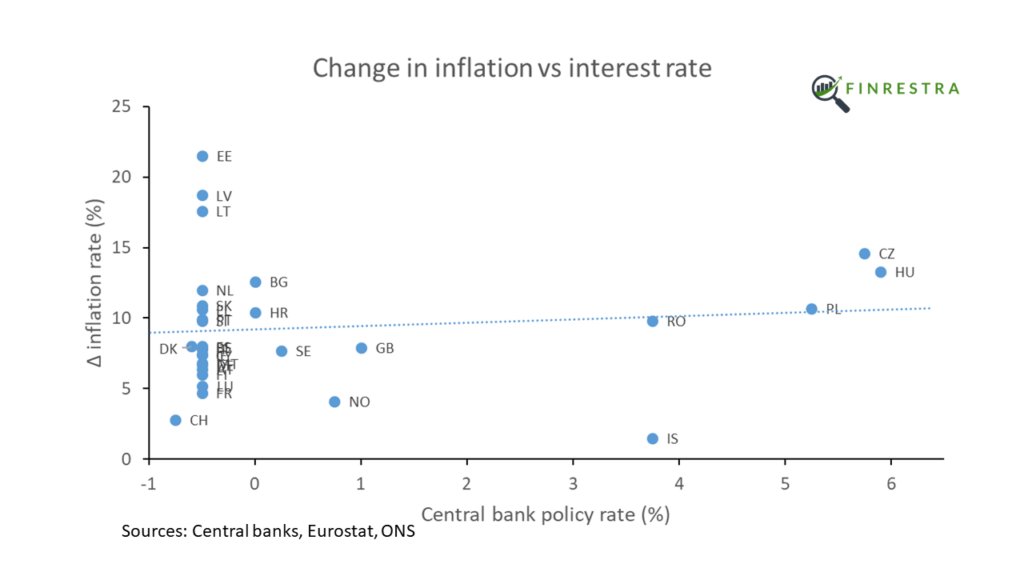

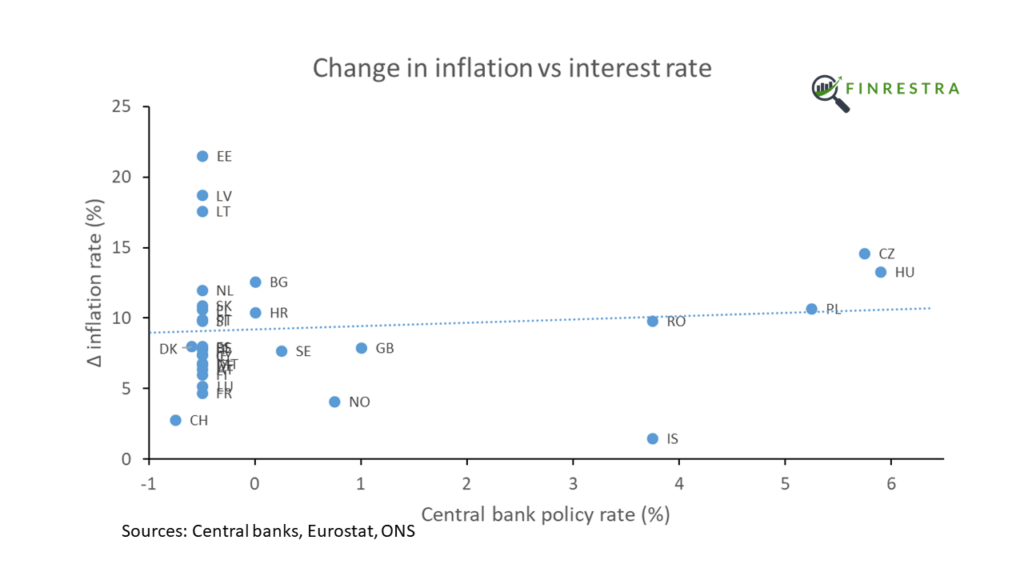

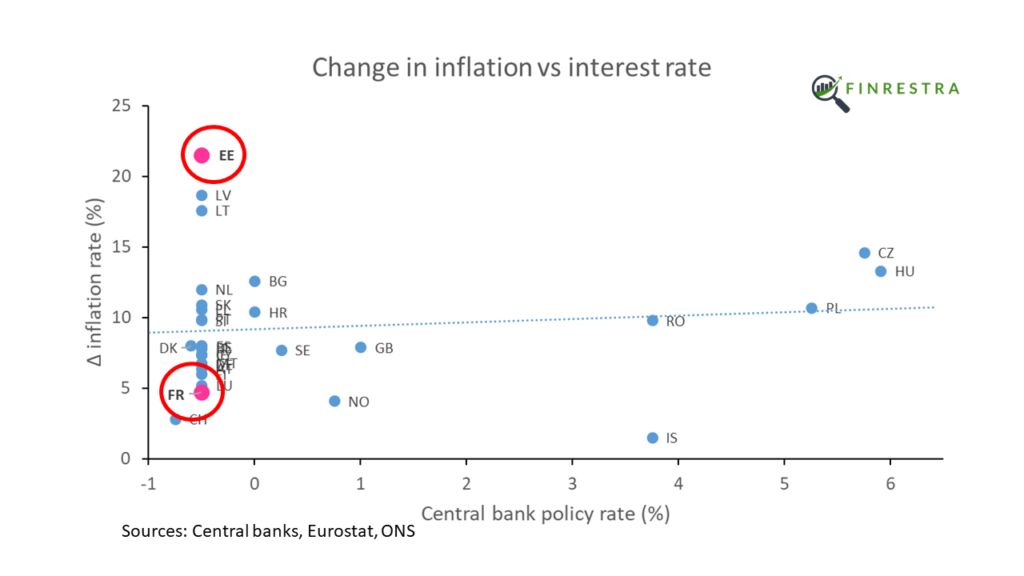

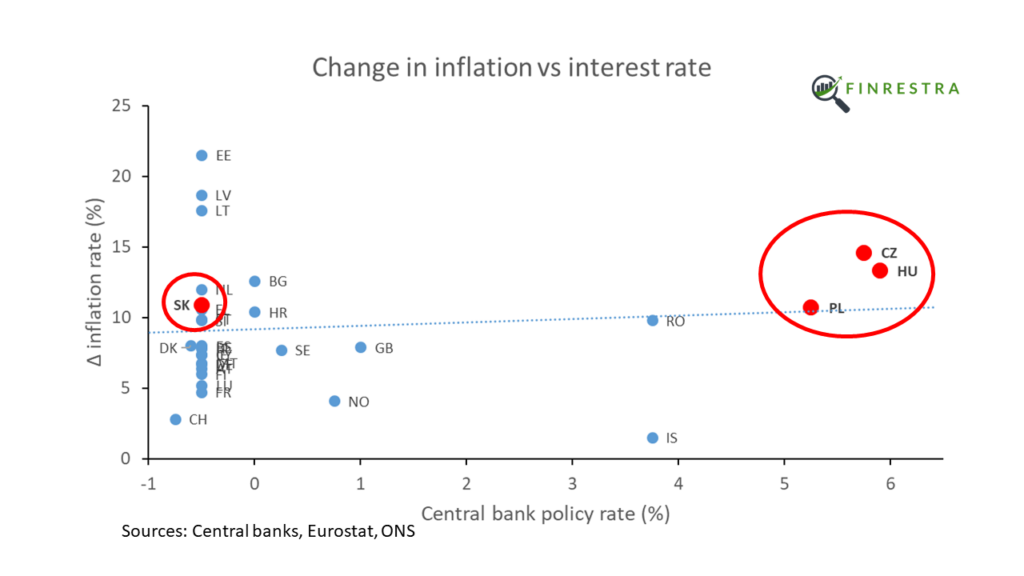

So here’s a slide that shows the increase in inflation and the central bank interest rate.

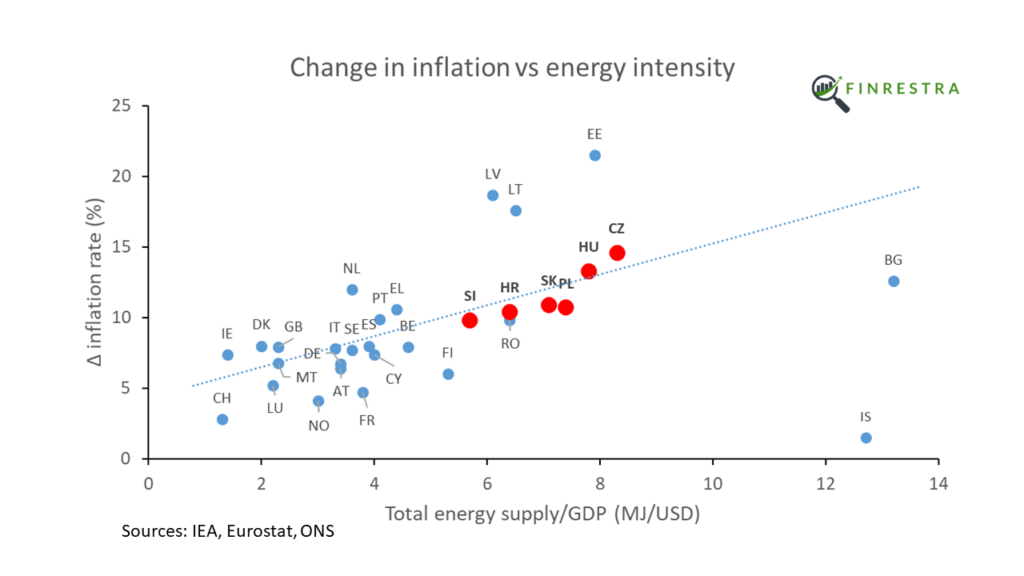

And so you can see that in certain central European countries like the Czech Republic and Poland the central bank has already increased interest rates a lot more than the ECB. But you can still see that there is no correlation between the central bank interest rate and the change in inflation in European countries.

Also from that previous video, you can see what is causing the different inflation rates between countries is mostly the energy intensity of the economy. So if an economy needs more energy to produce a euro of economic output, then the inflation in that country tends to be higher. This inflation has nothing to do with deposit facilities or TLTROs.

If you want to learn more about the ECB or European banks in general, please subscribe to this channel!

Thanks for watching!

Video version here:

This post contains links to sources and some extra analyses.

After years of low inflation, inflation in Europe has gone through the roof. Germany is experiencing the highest inflation in 70 years.

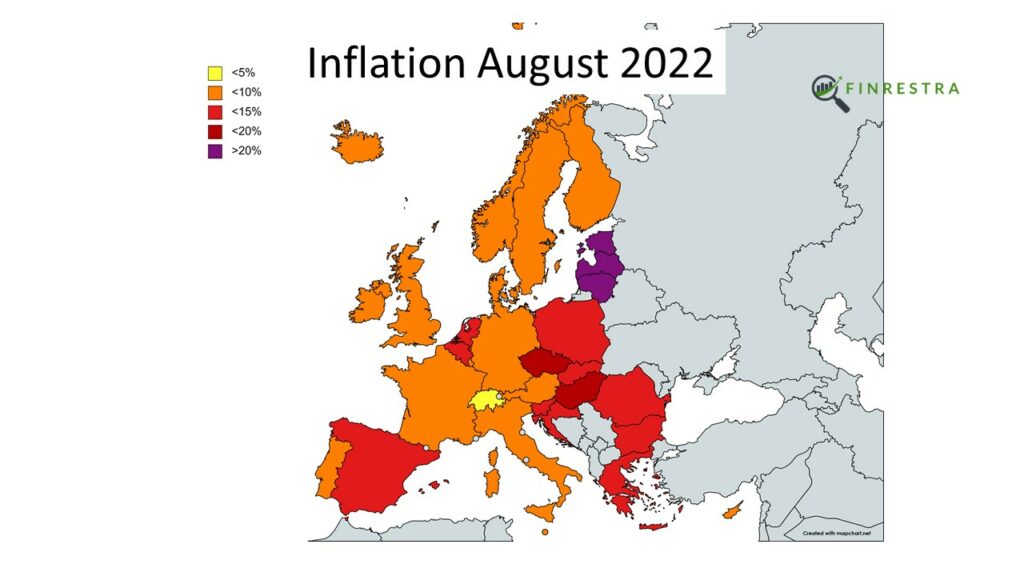

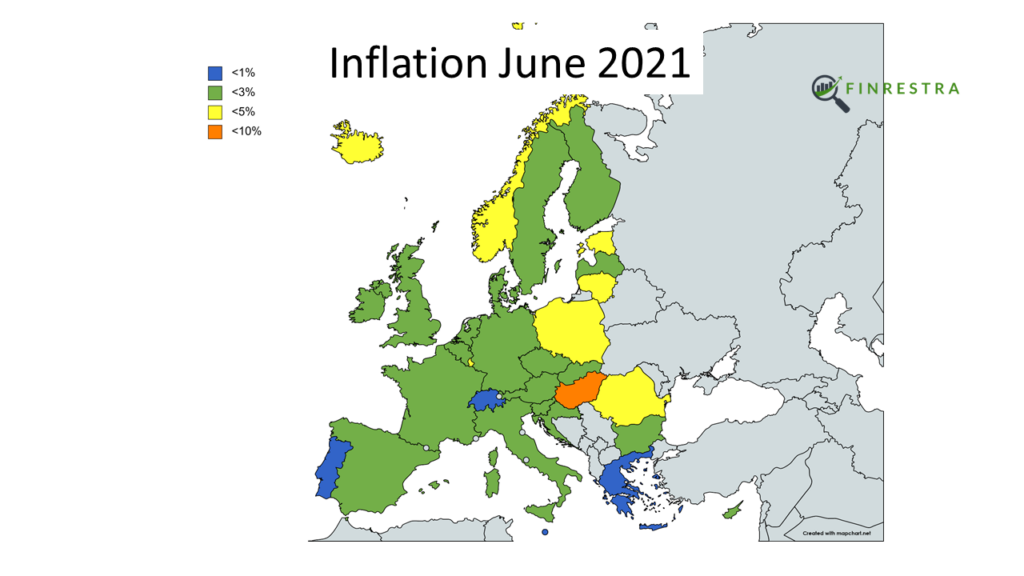

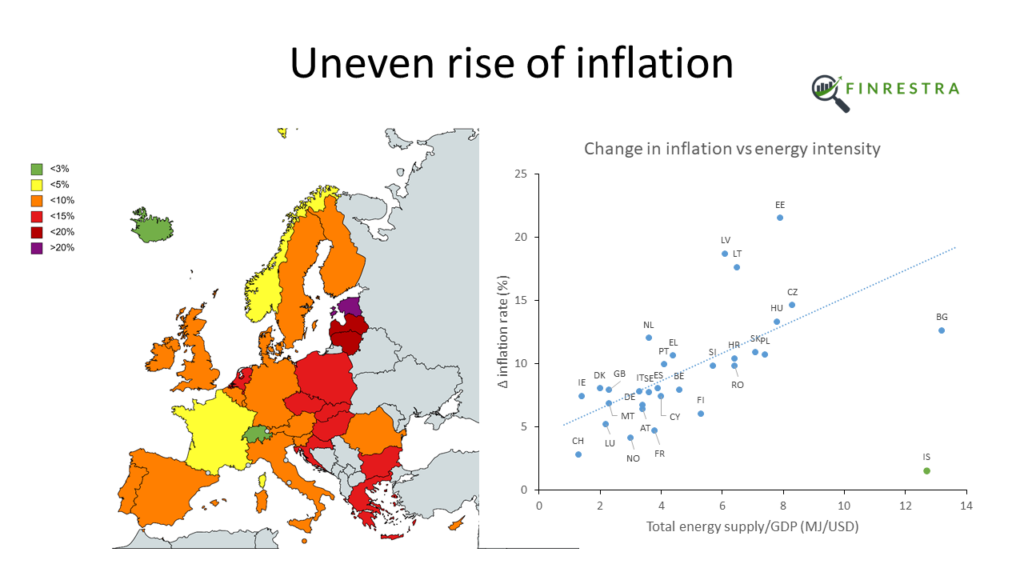

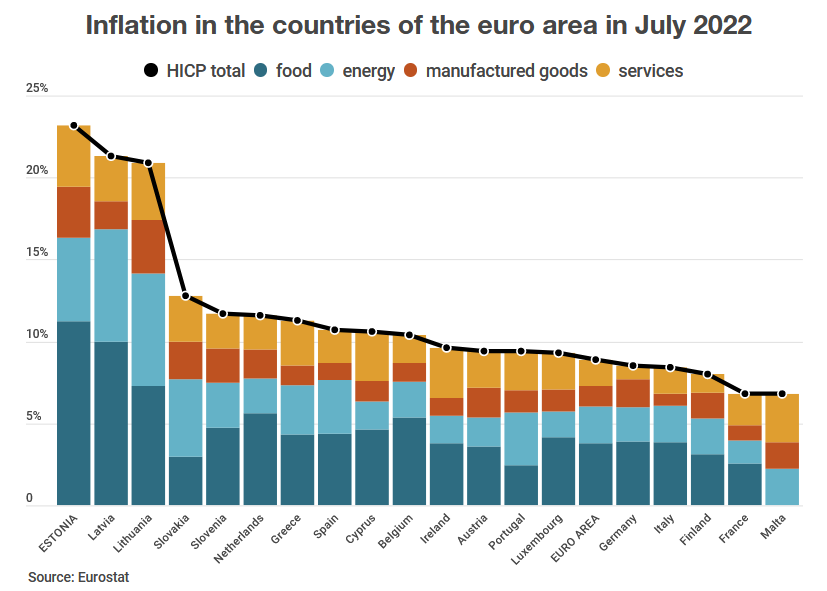

In June 2021, inflation was still close to 2%. In August 2022, it was above 10% in the European Union (EU) as a whole. But that number hides a remarkable divergence between countries. In Estonia, inflation reached a stunning 25% in August 2022. In France, it was 6.6%. In Switzerland, not an EU member state, inflation was just 3.3%.

A year before, in June 2021, inflation was very close to 2% in most European countries. With 5.3%, Hungary had the highest inflation. Inflation was lowest in Portugal, at -0.6%.

In this post, we’ll look at the change of inflation in 31 countries: the 27 member states of the EU, and the United Kingdom (UK), Norway, Switzerland and Iceland.

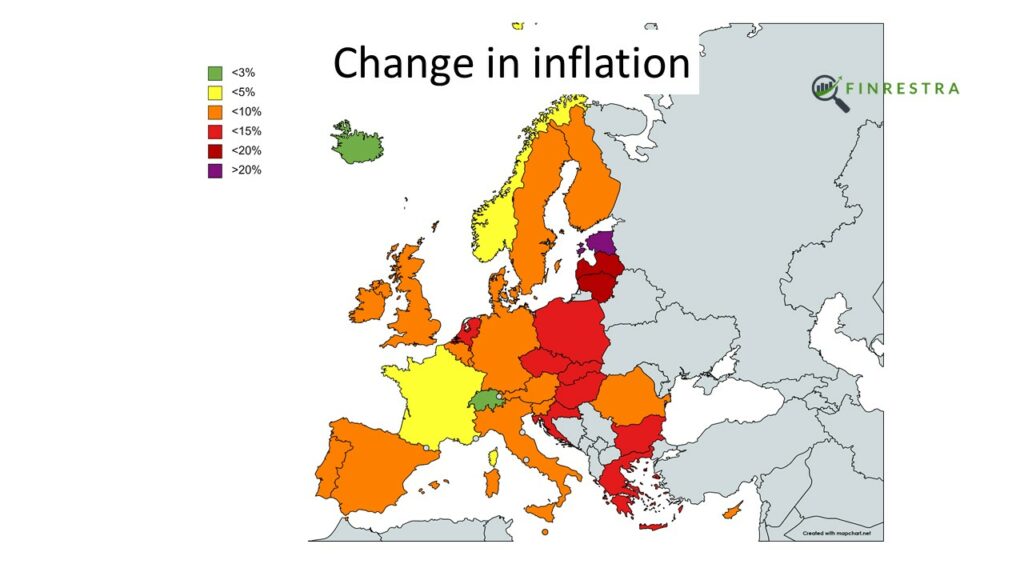

How can we explain the dramatic, uneven rise in inflation?

Consumers are paying a lot more for energy than they used to. Companies also face higher energy bills, which has an impact on the price of their goods and services.

But energy prices are set on international markets, e.g. for oil, gas, coal and electricity. Why doesn’t expensive energy result in a similar rise of inflation across Europe?

As the following figure shows, there is a strong correlation5 between the rise of inflation and the ratio of energy use to GDP6. As a general rule, the more energy a country needs to produce a dollar of economic output, the higher its inflation. Countries in Central and Eastern Europe have higher energy intensities and higher inflation rates than their Western European neighbors.

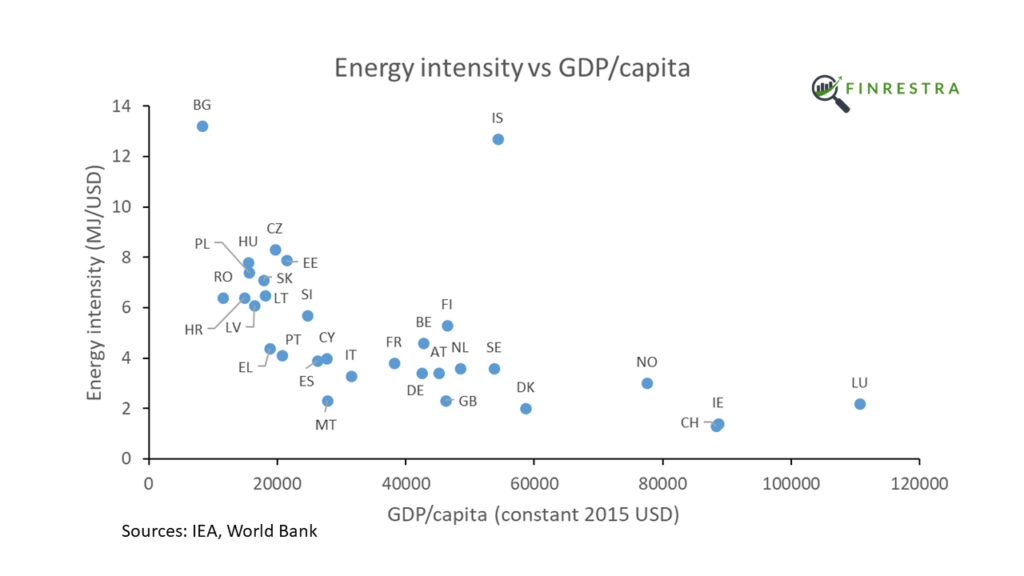

Countries with a lower GDP per capita tend to be more energy intensive.

So it’s not surprising that Central and Eastern European countries, who are relatively poor, are experiencing higher inflation than the West7.

But it’s not just an East-West story. Even within regions with similar GDP per capita, the more energy intensive countries experience higher inflation. For example Central Europe8,

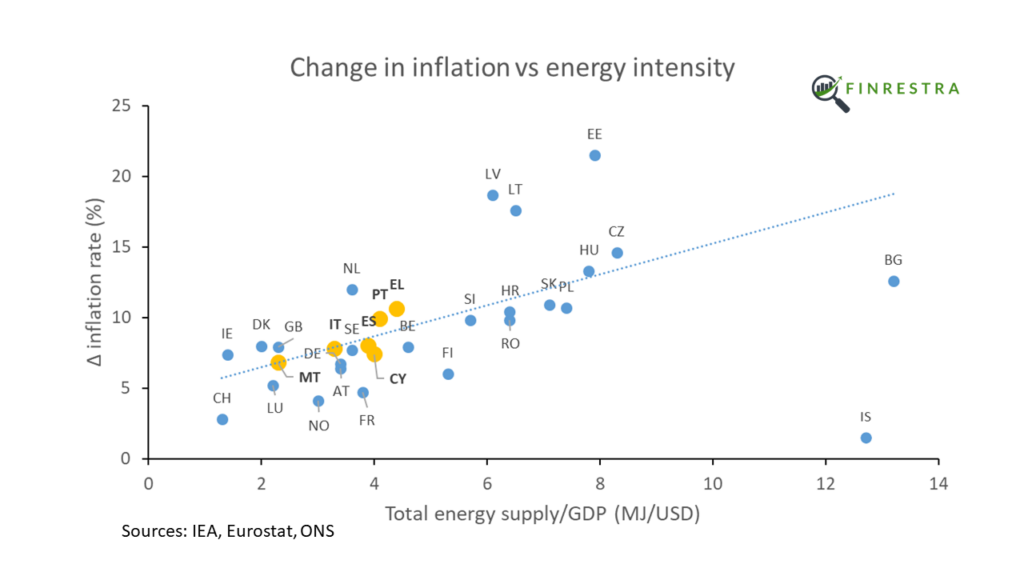

Southern Europe9,

and the Baltics10.

The picture is less clear in Western Europe. The energy intensity of Luxembourg and Ireland is distorted by the denominator (small countries with a very high GDP per capita due to the presence of international companies). France already limited energy prices in 2021. The Nordic countries are just weird ¯_(ツ)_/¯

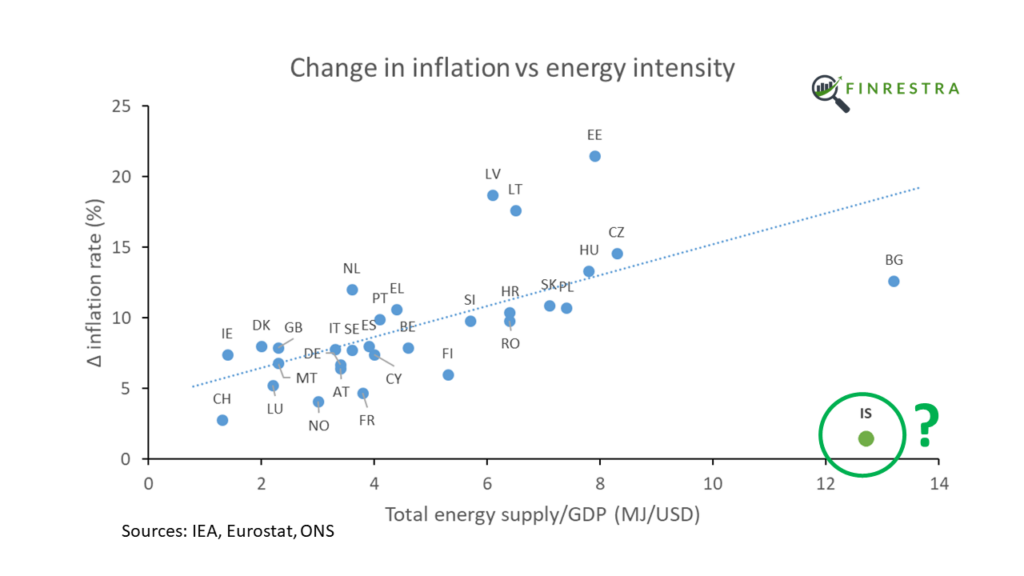

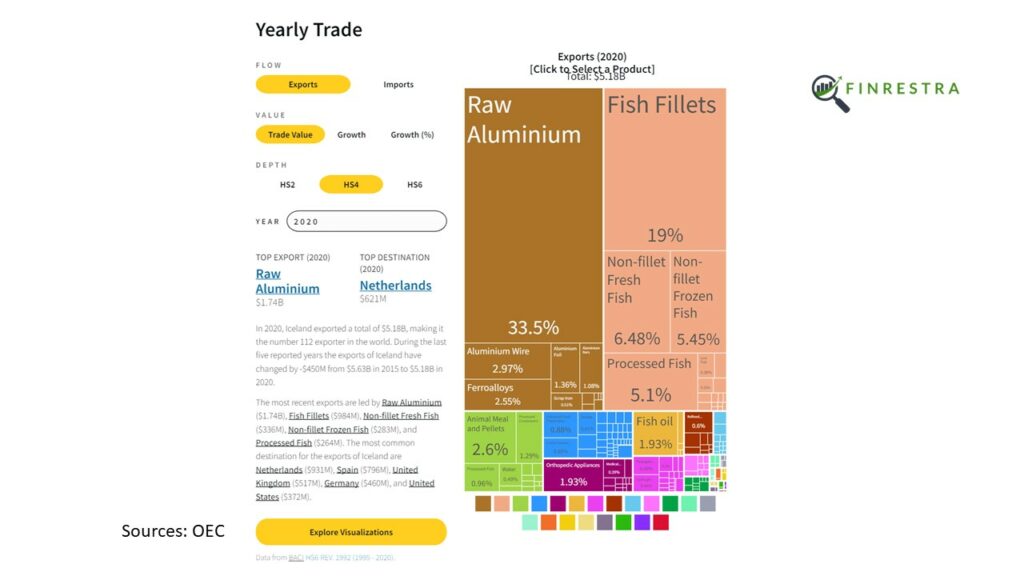

What’s going on in Iceland? Iceland is a rich country with an abnormally high energy use. Why doesn’t this result in much higher inflation?

Although Iceland is a small nation, it’s a big producer of aluminum.

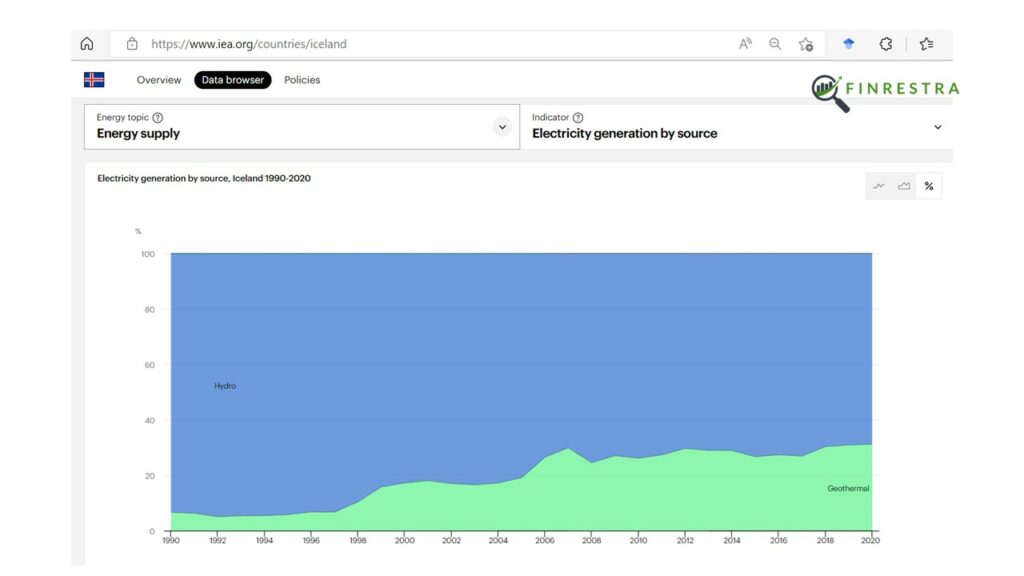

Making aluminum requires a lot of electricity. But all of Iceland’s electricity is generated from renewable sources.

So the Icelandic economy is less affected by higher fossil fuel prices than the rest of Europe. Fossil-free electricity also seems to be the explanation for the very low inflation in Switzerland.

What other factors could contribute to the rise of inflation?

According to economic theory (NAIRU, Phillips curve), when unemployment is “too low”, workers demand higher wages. And higher wages lead to higher prices.

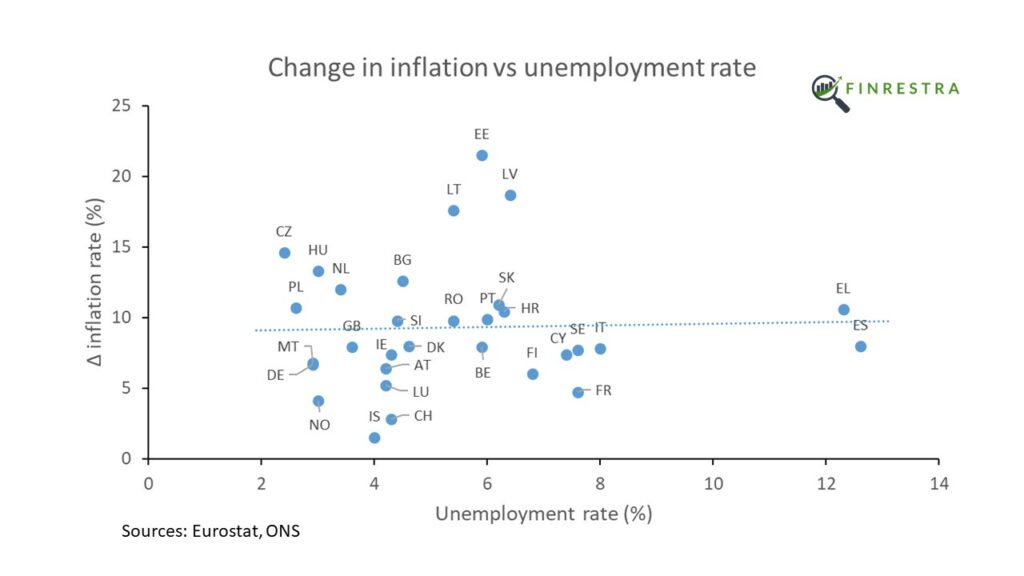

However, there is no correlation11 between unemployment12 and the change of inflation in Europe.

Inflation rose more in Spain and Greece than it did in Germany, although the German unemployment rate is much lower.

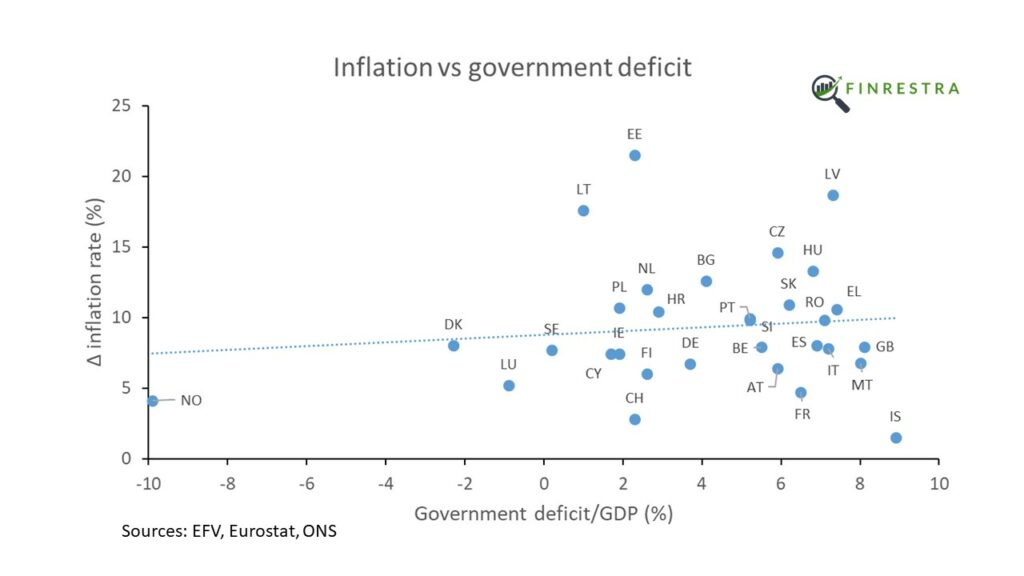

Do deficits cause inflation (Fiscal theory of the price level)? It makes intuitive sense that if the government spends more money into the economy than it takes away with taxes, this deficit leads to inflation.

However, there is no correlation13 between government deficits14 and the rise in inflation.

Denmark and the UK have the same change in inflation, although the Danish government ran a budget surplus in 2021, while the British had an 8.1% deficit. Finland and Estonia had similar deficits, but their inflation numbers are very different.

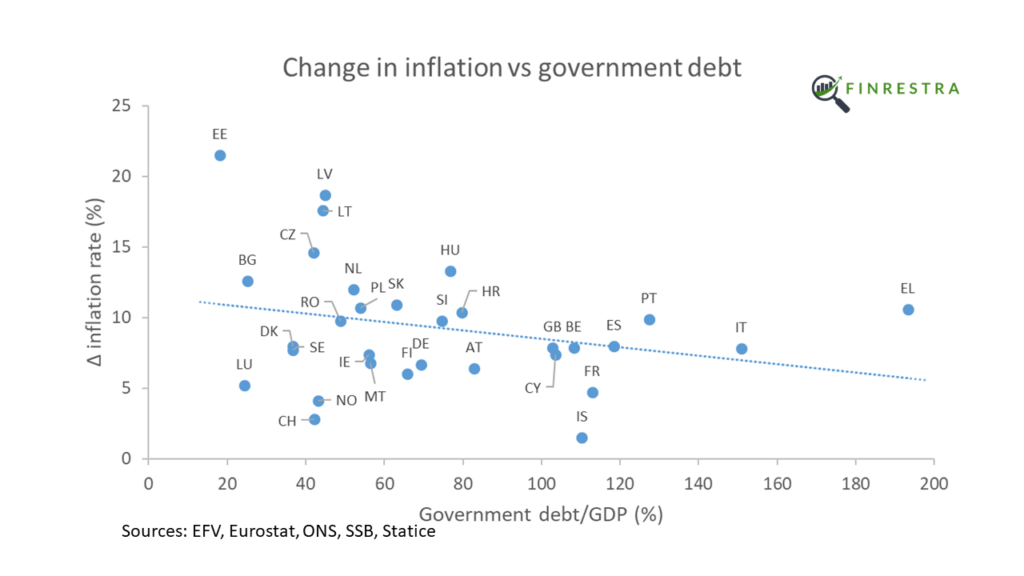

What about public debt? Maybe inflation goes up because people lose confidence in the sustainability of the debt. Or because governments choose to inflate away the debt.

However, there is a slightly negative relation15 between government debt and inflation16.

Greece, with its massive government debt, has experienced a smaller rise in inflation than the Baltic countries, where government debt is very low. Estonia has both the lowest government debt to GDP, and the highest inflation in Europe! Inflation is higher in the Netherlands than it is in Italy, although Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio is almost 100 percentage points higher.

Central bankers try to control inflation by changing interest rates. By influencing how expensive it is to borrow money, they influence prices of goods and services.

The picture shows central bank policy rates17 on June 1, 2022. Since that time, central banks have raised interest rates in an attempt to tamp down inflation.

But it’s not clear that interest rates have an effect on Europe’s inflation. In the euro area, where the ECB sets monetary policy for all 19 member states, inflation rose by 4.7% in France and 21.5% in Estonia.

In Slovakia, a country with a negative interest rate, the rise in inflation (+10.9%) is similar to neighboring Czech Republic (+14.6%), Hungary (+13.3%) and Poland (+10.7%), where policy rates were over 5%.

In conclusion, Europe’s worse inflation in generations is driven by energy. Conventional factors monitored by central banks don’t seem to play a role.

This work started as a small project I did during the summer, using June 2022 inflation instead of the change of inflation (see tweet below). In this post and in the video, I used the latest available data. I also added six countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Malta, Romania18 and Iceland) to the dataset.

If you have any questions or suggestions about this work, you can find me on Twitter @janmusschoot or mail me at jan.musschoot@finrestra.com.

For my professional services, please contact me on Linkedin or mail me at jan.musschoot@finrestra.com.

Twitter user Rasmus checked the data points I posted in June. His test shows that the regression line slope is different from zero:

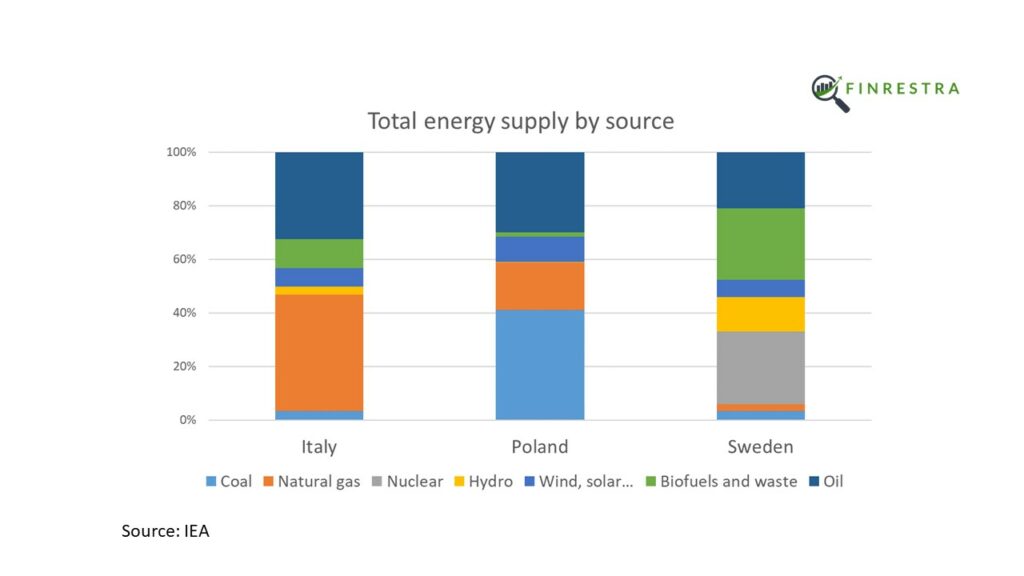

It is remarkable that there is such a strong correlation between inflation and energy intensity, given the different energy mix between countries. For example, natural gas is the most important fuel in Italy. Poland mostly burns coal, while Sweden relies on wood. While natural gas and coal prices are up hundreds of percent, that’s not the case for oil or nuclear.

I suspect the strong relation is due to electricity prices, which are often determined by the price of natural gas.

Other complicating factors that my analysis doesn’t take into account are price caps for energy (e.g. France), and the energy intensity of exporting industries (which should have less of an effect on domestic consumer price inflation).

The three Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) are outliers. Their inflation is much higher than we’d expect based on their energy intensity. It’s not obvious that the fact that they share a border with Russia is the explanation. Finland, a euro country like the Baltics, also borders on Russia and has a relatively low inflation.

According to the central bank of Estonia:

There are several reasons why inflation is higher in the Baltic states than the average in the euro area. The share of energy goods in the purchasing basket of consumers in the Baltic states is larger, which has affected the rise in the price of the consumer basket. Natural gas and electricity were a little cheaper in the region before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but prices have now caught up to those in other countries.19

Energy statistics – an overview (Eurostat)

From where do we import energy? (Eurostat)

European natural gas imports (Bruegel)

Carbon intensity electricity (Electricity maps)

Electricity prices (euenergy.live)

Real-time electricity tracker (IEA)

National policies to shield consumers from rising energy prices (Bruegel)