Listen to this podcast on Spotify!

Text:

There’s a consensus that European banks need to consolidate.

For example, in the report for the European Parliament that I talked about in the previous episode, the authors write that if UniCredit’s takeover of Commerzbank succeeds, quote: “it could plausibly mark the start of a new cycle of cross-border consolidation”.

However, banks have never stopped consolidating. You just need to look at the data.

If you do that, you’ll see that the consolidation of Europe’s banks is almost over…

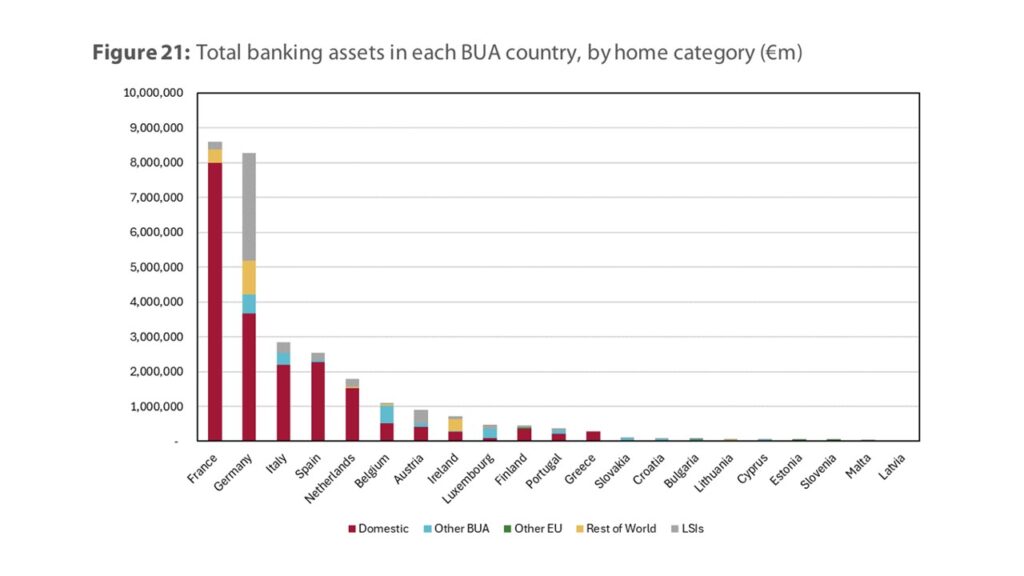

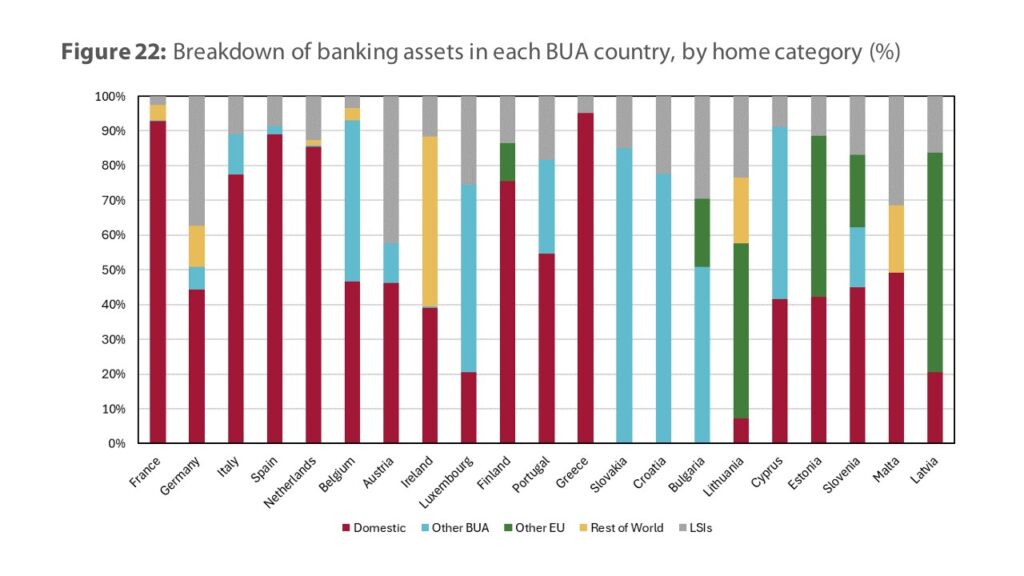

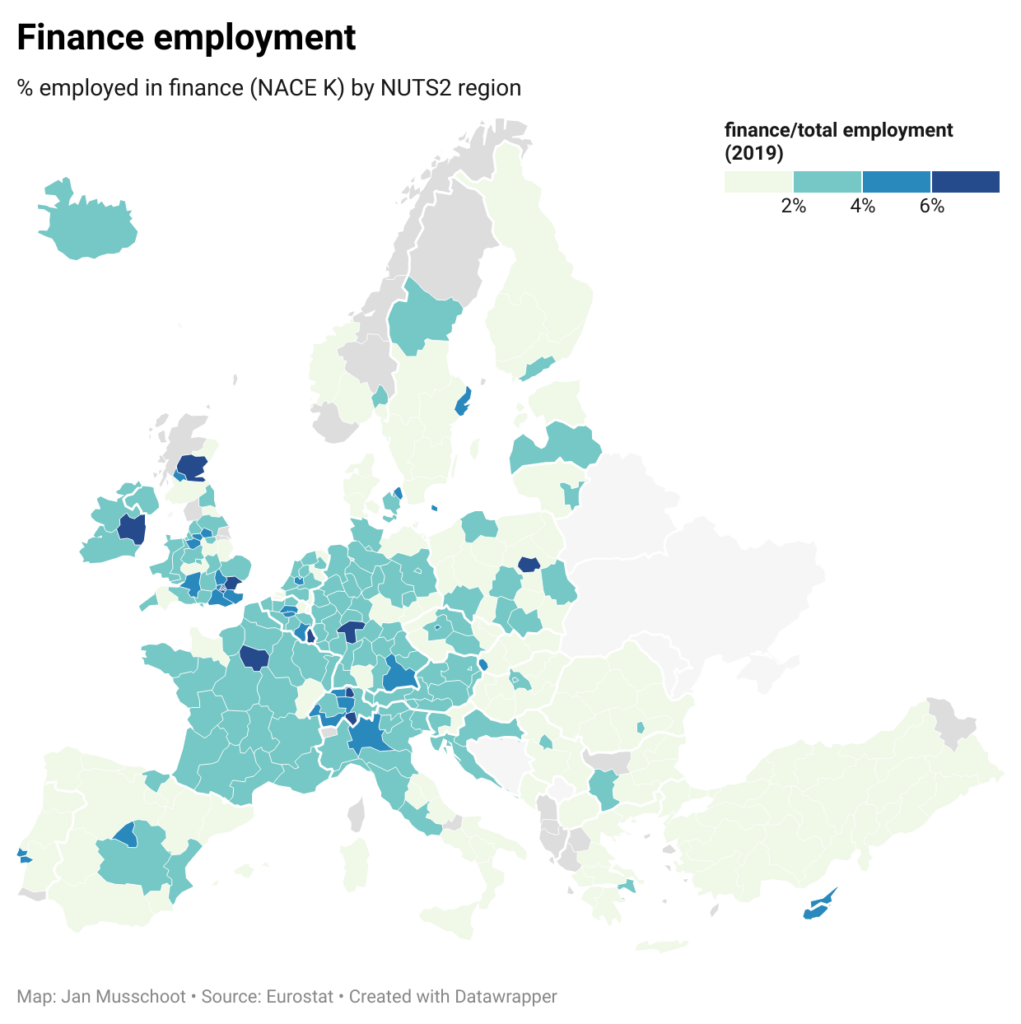

So, how much concentration is there in the banking market?

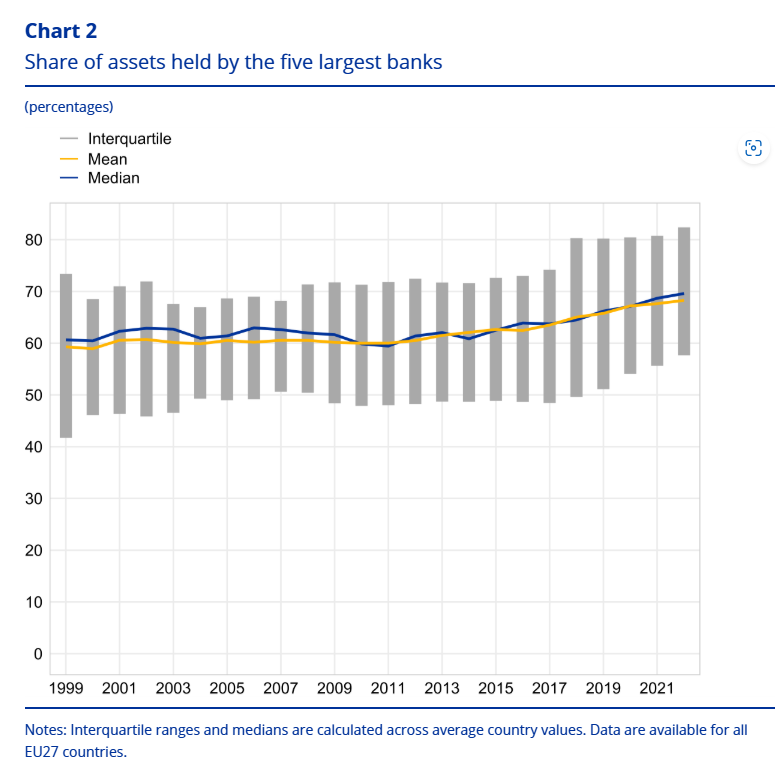

The European Central Bank publishes a statistic called Shares of the 5 largest credit institutions in total assets. (Where credit institution is a fancy term for banks.)

This metric looks at what percentage of the total market, measured by the assets on their balance sheets, is controlled by the five largest banks.

In most of the countries in the EU, the top five control more than 70% of the national banking system.

And this concentration has either been stable or rising.

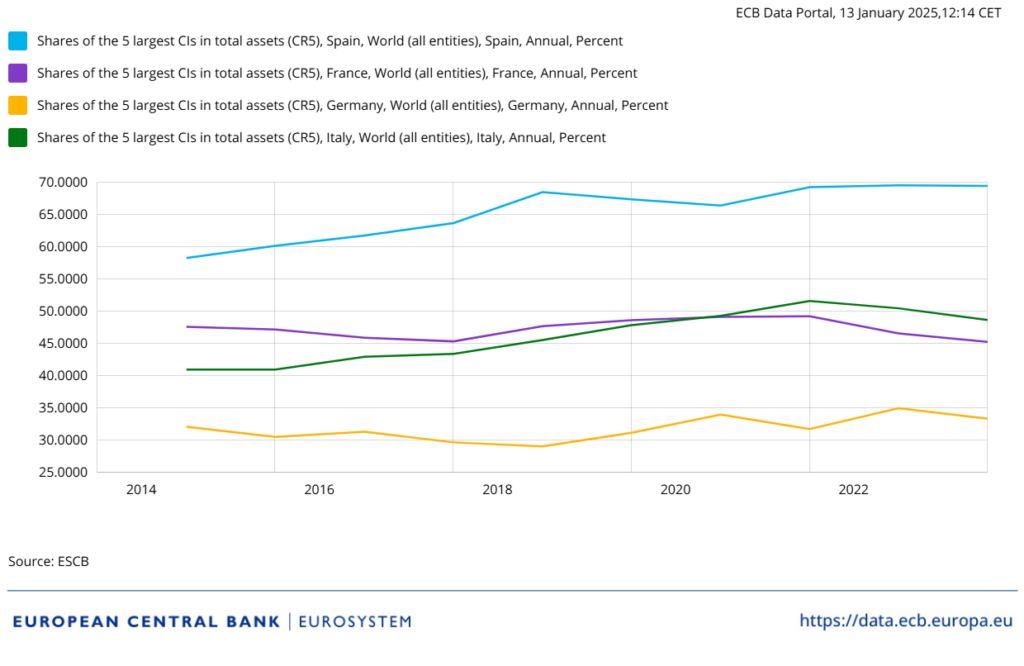

If you look at the big four EU countries, the largest banks in Spain and Italy have significantly increased their market share over the past 10 years.

In France, the concentration has remained constant at about 47 percent.

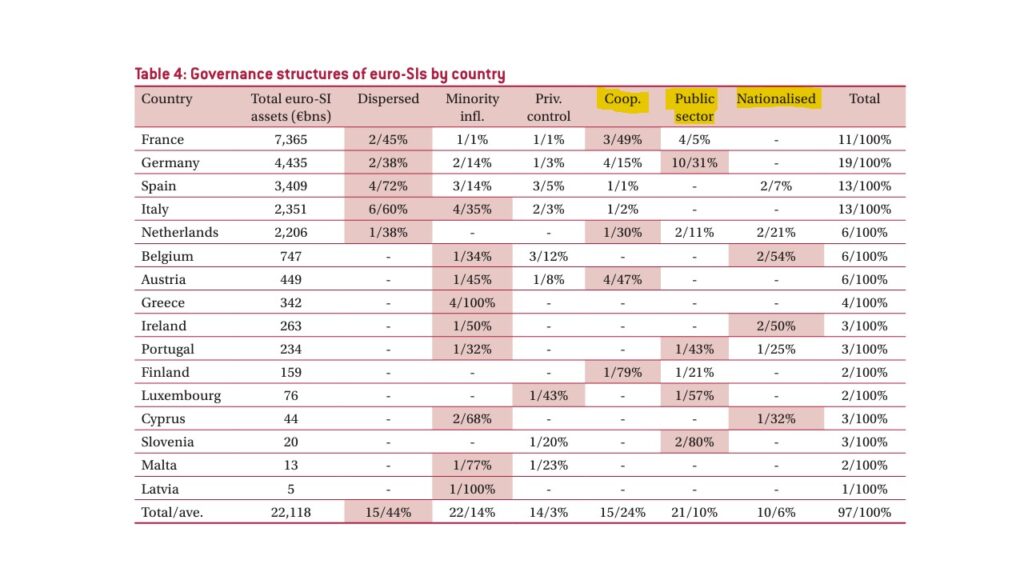

This may be surprising if you listened to the previous episode, where I told you that 5 large French banks control most of the French market.

The explanation is that banking groups like Crédit Agricole or BPCE are made up of lots of smaller banks that typically only operate in a certain region.

If the total assets of the French top 5 would be based on the consolidated groups, the ECB’s figure would show a very concentrated market in France.

The same is true in Germany. If you’d take the (almost) 700 cooperative banks of the VR group together, the top 5 concentration would go up a lot.

So the narrative of a fragmented market that hasn’t consolidated, already falls apart if you look at the big countries.

But the rising concentration is most apparent if you look outside of the euro area.

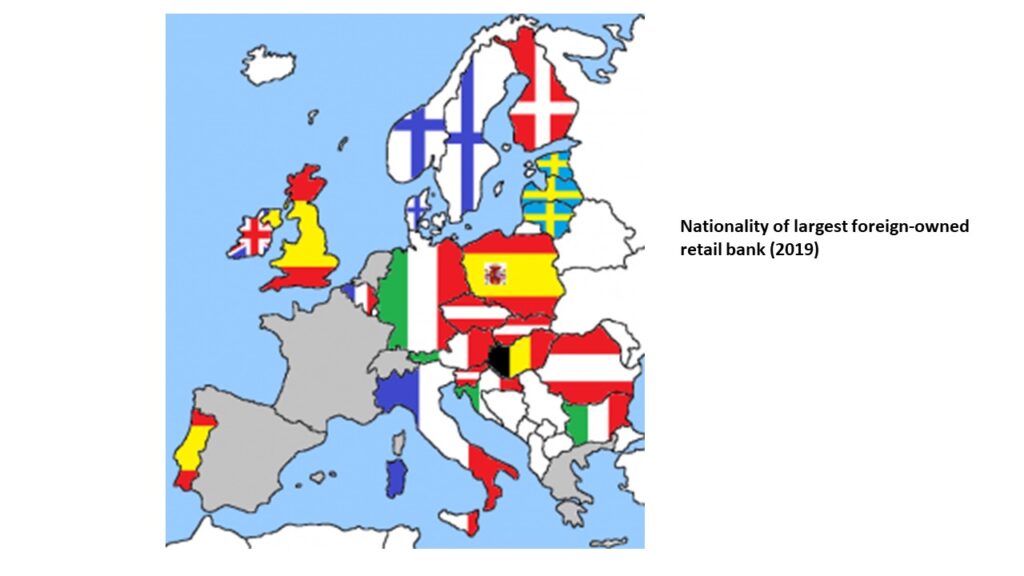

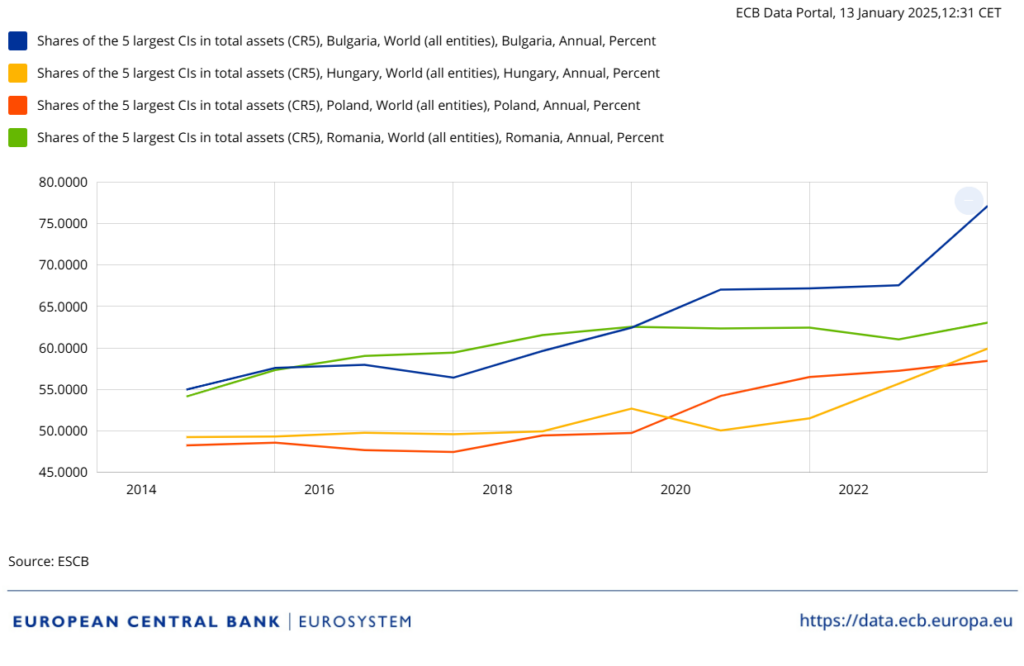

Let’s take a look at Central and Eastern Europe.

In Poland, Romania, Hungary and Bulgaria, some of Europe’s fastest growing economies, the concentration has gone up a lot.

This is mostly due to large banks buying up smaller competitors.

Sometimes foreign banks left a country to focus elsewhere.

Sometimes they stayed and expanded their market share.

This is the cross-border consolidation that policy makers have been hoping for.

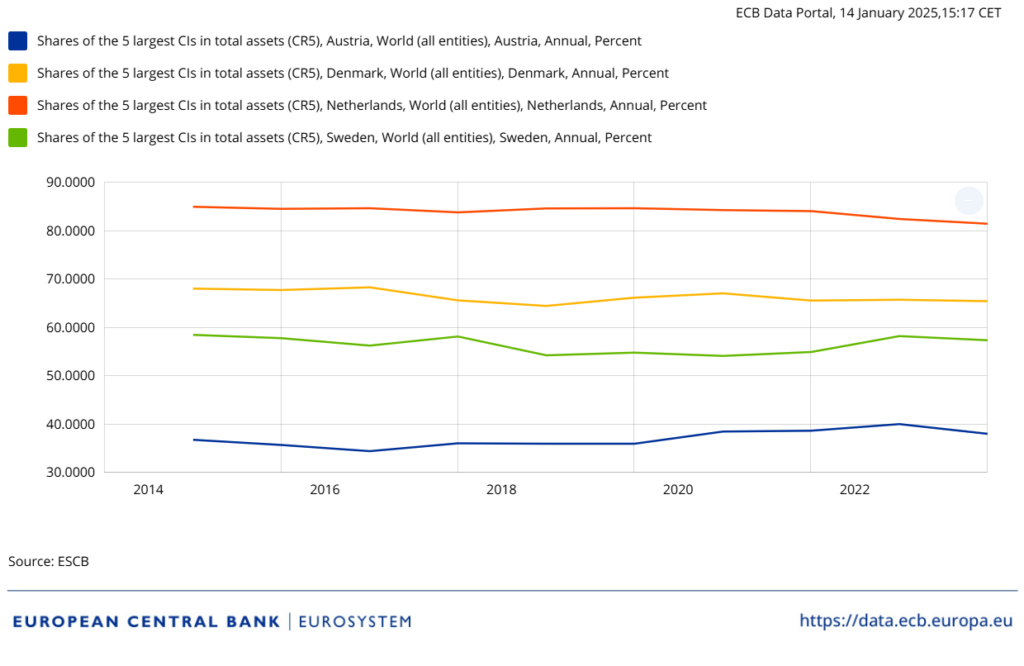

We could also look at some mid-sized economies in Northern and Western Europe.

For example, in the Netherlands, three Dutch banks basically form an oligopoly.

In Denmark and Sweden, the market has been pretty stable.

But that’s gonna change: Nykredit, one of the top banks in Denmark, recently announced the acquisition of a domestic rival.

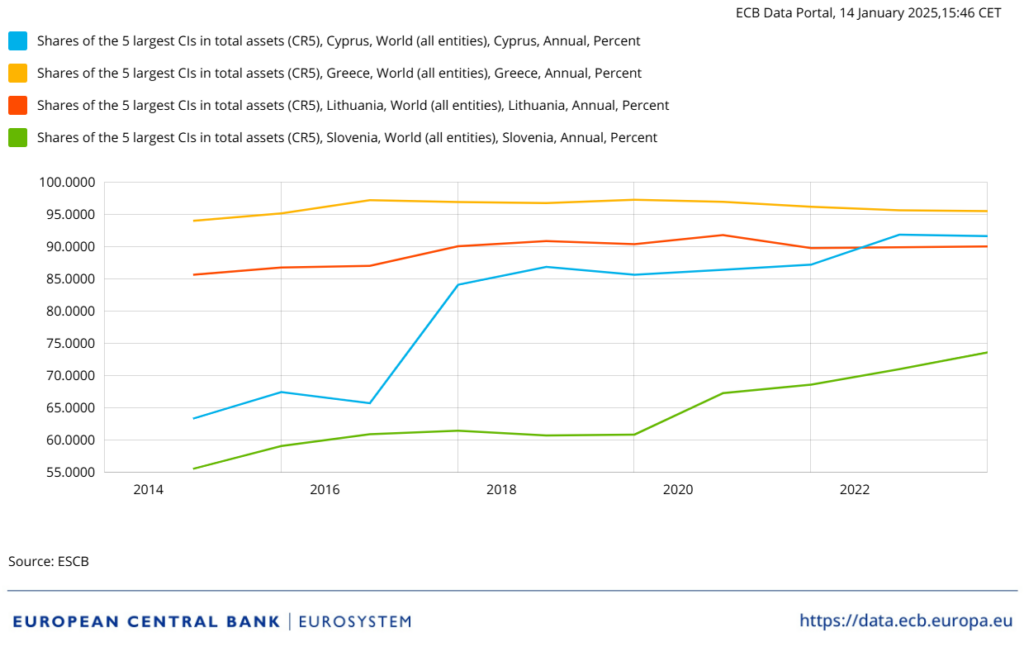

And I can easily pick some smaller economies with banking systems that have become or remained very concentrated.

In Lithuania, Slovenia and Cyprus, the market isn’t big enough to support many profitable banks, so the concentration is very high.

In Greece, although it has a population of about 10 million, the entire market basically consists of 4 domestic banks.

That’s the picture at the national level.

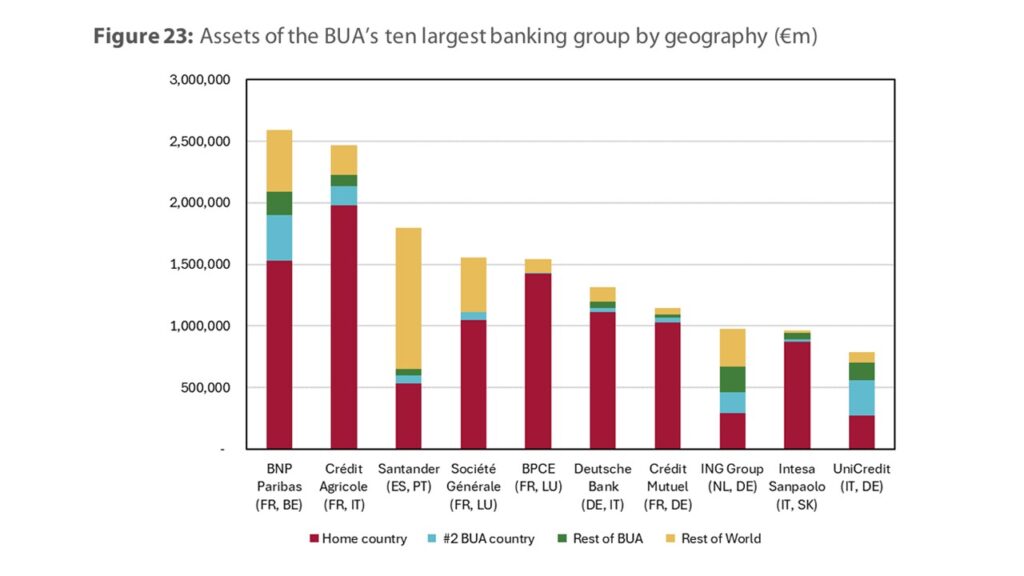

We can also look at the largest banking groups in Europe.

And here I’m gonna expand the scope beyond the European Union, and include countries like The United Kingdom and Switzerland.

In 2018, the German consulting firm ZEB published a report on the European banking market. In their report, they listed the 50 largest European banks at that time.

It is now seven years later.

Since then, three major banks have disappeared because they were acquired by their competitors.

There was one in Spain and one in Italy, but by far the biggest was Credit Suisse, which was acquired by UBS when Credit Suisse was failing due to a bank run.

I’m gonna talk about bank runs in a future episode, so please subscribe if you don’t want to miss that.

Right now, there are three more active takeover bids for top 50 banks.

The most famous one is the acquisition of Germany’s Commerzbank by UniCredit.

Back in Italy, UniCredit also wants to buy Banco BPM.

And if BBVA manages to acquire Sabadell, the Spanish banking market will resemble the Dutch one, dominated by three domestic giants.

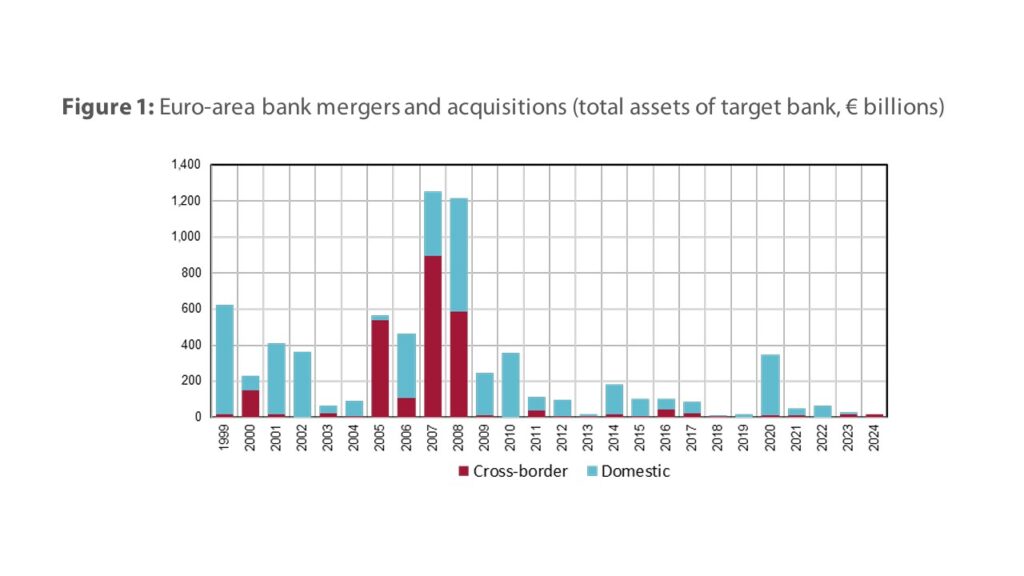

So it’s just not true that M&A was dead before the bid for Commerzbank.

Finally, I wanna comment on the first chart in the report from the Bruegel guys for the European Parliament, that I talked about in the previous episode.

That chart showed M&A deals measured by total assets of the banks that were acquired.

Almost by definition, this method has a bias for so-called universal banks.

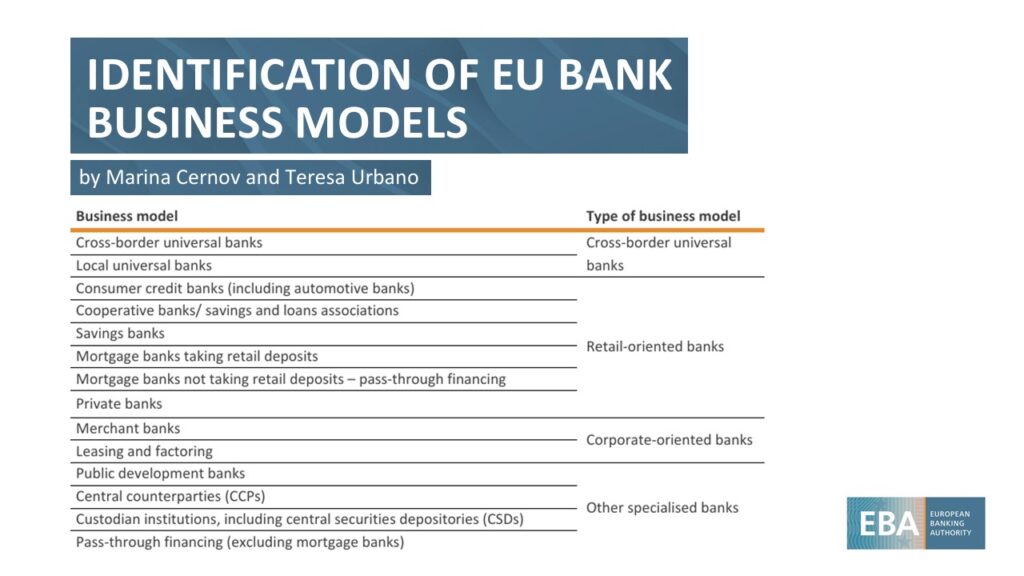

So maybe I should explain what universal banks are.

Universal here does not mean global banks or banks that are active in lots of different countries.

No, a universal bank is a bank that offers its services to a range of different clients, from retail to corporates.

These banks offer mortgages to home buyers.

And they also make loans to businesses.

These universal banks have many clients, which means they have many loans and deposits.

So overviews of the largest banks by assets almost always just show universal banks.

But by looking only at these large banks, you miss niche players that are specialized in a certain segment of the market.

For example, there has been consolidation among custodian banks.

I think maybe three people on the planet care about securities services, so I’m gonna skip those custodian banks.

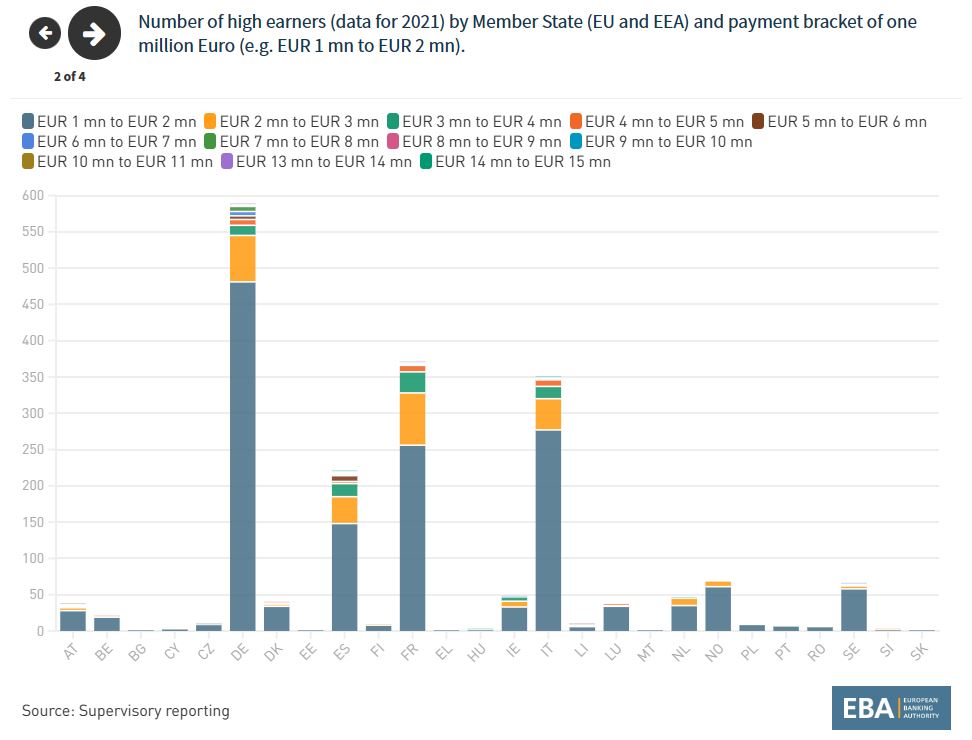

But there have also been lots of deals between private banks.

Private banks work for rich families, offering wealth management services.

UBS buying Credit Suisse was of course the largest deal in private banking.

But there’s been plenty of activity in the private banking space in countries like Belgium and the Netherlands.

In Germany, BNP Paribas and ABN Amro have recently increased their footprint.

But it’s not just large banks that are expanding.

Swiss UBP has been on a buying spree lately, taking over the private banking activities of larger groups in a number of countries.

So taking all of this together – the rising concentration at the national level, the mergers of large banks, and the consolidation among specialized banks – the narrative that a new wave of consolidation of European banks could kick off is totally false.

Out of the spotlight, banks have never stopped consolidating.

They just did it gradually.

And if you haven’t paid attention during the past decade, or if you’ve only watched the large banks in France and Germany, Europe’s banking concentration may suddenly seem quite different.

OK, that’s it for this episode.

Thanks for making it all the way till the end, and till next time 🙂