The rise of Donald Trump and the Brexit referendum have led to a lot of commentary on democracy itself. Understandably these comments usually come from people who dislike the outcome. But that does not mean they do not have a point.

This article looks at the democratic process up to the casting of the ballot. How the votes are counted, what is done with the result, how votes are translated into representatives and policy, the influence of non-elected lobbyists on legislation… is outside the scope of this post.

If this post comes across as cynical, it’s probably because it describes reality.

The fantasy

A lot of pundits have a cartoonish view of democracy, which can be summarized as follows:

- People get informed on issues, programs and candidates

- Voters weigh the arguments

- A rational evaluation leads to a decision in the form of a vote

Even if commentators do not actually believe this is how it works, their opinions betray that they think it is how democracy should be in the best of worlds.

Let us now scrutinize how elections work in reality. As always on this website, we take a step by step approach to make all assumptions explicit. As a thought experiment1, a number of possible changes to the existing election process are suggested. I pose some fundamental questions that should be answered by those who are not satisfied with the status quo.

What’s on the ballot?

Herman Van Rompuy, the former President of the European Council and probably best known for this encounter with UKIP leader Nigel Farage, thinks Britain should not have had a Brexit referendum at all. And neither should any other EU country.

This paternalistic view is shared by many in the elite. They know what’s best and the lower classes shouldn’t interfere with their projects:

Referendums are a reminder why you should never leave important decisions in the hands of the people. #Brexit #TheMassesAreAsses

— CJ Werleman (@cjwerleman) June 24, 2016

I have read similar comments about the Trump candidacy, which argued that he never should have been allowed to run for president.

So the fundamental question is: who decides which topics and candidates are acceptable? Can democracies outlaw ideas and people with a broad support indefinitely?

Does such a restriction not depend on a non-democratic agent in the state? A court or the military which can overrule certain choices? Even a silly topic like naming a ship by the public can cause trouble, as the Boaty McBoatface controversy demonstrated.

Switzerland is a rare2 case of a country with regular referenda. Most countries do not allow for such direct democracy. Instead, representatives are appointed who make decisions on behalf of the people.

To be eligible, candidates must get their name on the ballot. In practice, this requires a power struggle within political parties. This struggle often happens behind the screens. The conflict between Trump and the Republican establishment has been unusual by revealing this process to the public eye.

Informing and influencing

Once there are a number of options, the question becomes how voters choose between them3.

Political campaigns try get voters on their side. Unlike what some hope, elections are not won by having the best program or by having knowledge of issues. Many people vote based on how much they like a person. Or how much they dislike the opposition. Emotions, not reason, win elections.

After the victory of Leave4 we hear pundits exclaim: “Shock horror! Politicians lied to win the election!” This conveniently omits the fact that politicians lie all the time about everything. They make all sorts of promises to get elected. The relevant measure in elections is not the truth, but the number of votes.

Opinions are shaped in part by the traditional media (tv shows and newspapers). These make a selection out of a vast sea of potential news stories. They decide which politicians get airtime. Or how to frame institutions like the EU. British leftist professor Simon Wren-Lewis laments the hostile attitude of the tabloids towards the EU.

It is undoubtedly true that newspapers have written negatively about the EU for years, but again: who is going to stop this? Should there be a censorship commission that decides: per X negative articles, there ought to be Y positive ones and Z articles with objective information? And even more importantly: who will force the public to read these articles? Do people who argue for a more objective press have any idea on how to implement their dreams, without being laughed out of the room as philosopher-kings?

A recent factor influencing opinions are the internet and social media. People search for information online and they comment on news stories. This leads to behavior that is not always approved by the media, which has its own political preferences.

@Soccerpolitics @counti8

1. "The comment section is out of control."

2. Shuts down comments.

3. TRUMP.— Χριστόφορος ᛒᚢᚱᛞ (@christopherburd) June 14, 2016

Some have even suggested to shut social media down to avoid unwanted electoral outcomes:

The only way, it seems, that the tech world can help stop Donald Trump from becoming […] the president of the United States, is […] to pull the plug on social media until this election cycle is over.

Such sentiments fuel conspiracy theories5 claiming that tech companies plot against Trump, for example by rigging Google search results.

Furthermore, online filters and segregation make democratic outcomes hard to accept and understand6.

An appeal to everyone I know who works at Twitter, Facebook, Google etc, and for the people who influence them pic.twitter.com/TRBTbZHrxG

— Tom Steinberg (@steiny) June 24, 2016

"I have about 3,000 friends on Facebook — and all but three were voting ‘Remain.’" https://t.co/OFNcorC5f5

— Ezra Klein (@ezraklein) June 24, 2016

Complicating things further, it should be assumed by default that opinions are being manipulated online. High stakes elections almost guarantee the involvement of hackers. Bloomberg published a must read article about this phenomenon in Latin America7. I strongly recommend it for everybody who is interested in politics!

Who’s allowed to vote?

A big question in democracy is who has the right to vote. For example, women and the poor were historically excluded from voting.

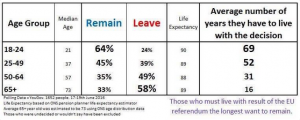

Polls have shown different preferences per age group on the Brexit referendum:

Some have used this to argue that old people do not have the moral right to force a decision on younger generations. But is anybody prepared to draw the logical conclusions of this? Should voting rights on long-lasting issues be granted according to the remaining life expectancy of the electorate? It could just as well be argued that old people have more experience and wisdom, so they should get more votes.

Mobilizing voters

It is not enough for campaigns to influence people. It is crucial that voters make the effort to show up to the voting booth. This seems to have been a crucial element in the Brexit referendum:

Turnout % of each age group in the #EURefResults:

18-24: 36%

25-34: 58%

35-44: 72%

45-54: 75%

55-64: 81%

65+: 83%via @SkyData

— MLMS (@mylifemysay) June 25, 2016

This teaches an important political lesson. Persuasion in itself means nothing when it is not backed up by action.

Intimidation and fraud

When voters show up at the polling station, fair elections depend on the possibility to freely make their choice (irrespective of how much propaganda went into forming it). Regimes have been quite creative at rigging elections. For example by not allowing voting secrecy or by ballot stuffing. See Wikipedia for a long list of ways to cheat in elections.

Conclusion

Democracy is one way to organize participation in legislature and to legitimize the ruling class in society. It would be nice if pundits and the public were more aware of the assumptions behind the democratic process and its limitations.

Political scientists could do a useful job spreading this fundamental awareness, rather than opining on all sorts of minute details of political campaigns.

But of course, this leads us back to the role of the press and the selection of topics 🙂

- This does NOT mean that I advocate any of these changes!

- Unique?

- This overlooks an important point. When people feel neglected or cannot vote on certain topics, they tend to cast protest votes when they have the opportunity.

- A majority voted for the UK to leave the European Union in the Brexit referendum.

- Being a conspiracy theory does not make it false.

- Never underestimate the power of self-selection, but that’s the topic for another post.

- Excerpt: “Rendón, says Sepúlveda, saw that hackers could be completely integrated into a modern political operation, running attack ads, researching the opposition, and finding ways to suppress a foe’s turnout. As for Sepúlveda, his insight was to understand that voters trusted what they thought were spontaneous expressions of real people on social media more than they did experts on television and in newspapers. He knew that accounts could be faked and social media trends fabricated, all relatively cheaply. He wrote a software program, now called Social Media Predator, to manage and direct a virtual army of fake Twitter accounts. The software let him quickly change names, profile pictures, and biographies to fit any need. Eventually, he discovered, he could manipulate the public debate as easily as moving pieces on a chessboard—or, as he puts it, “When I realized that people believe what the Internet says more than reality, I discovered that I had the power to make people believe almost anything.”” (emphasis mine)