In the thread below, Benjamin Braun explains Germany’s political economy. More specifically, he and Richard Deeg studied the interaction between the financial and non financial corporate (NFC) sectors.

Let me try to summarize the argument.

The German NFC sector has high profits (1) and runs a trade surplus (2).

(1) enables companies to finance their own investments. They don’t need to borrow money from banks.

(2) leads to an inflow of reserves and deposits at banks. As a result, German banks lend to foreign entities.

This seems a sensible story.

However, I don’t agree with the conclusion:

First of all, I highly doubt any policymakers really want to help German banks. If that were the case, the monstrosity of publicly owned, unprofitable banks would have been cleaned up by now.

But even if German politicians cared, it’s not clear that stronger unions or higher wages would be more than a drop in a bucket.

A higher demand for credit would have an immediate positive impact on German banks. And there is a lot of room for growth.

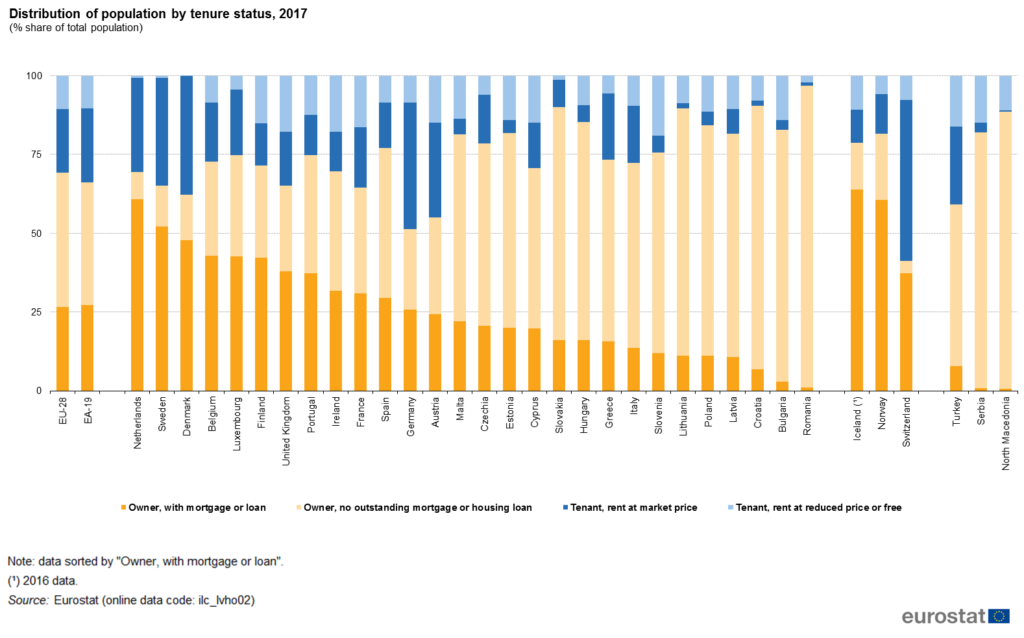

Home ownership in Germany is low compared to non-German speaking countries, as you can see in this picture from Eurostat.

Stimulating home ownership would boost the demand for mortgages.

More investment by the government, as called for by industry and labor unions, would also increase the domestic supply of assets for banks if it’s funded by bonds instead of taxes.

If Angela Merkel wants some more advice, she can leave a comment 🙂