I recently started working at the Social and Economic Geography research group of Ghent University, in the team of professor Ben Derudder. We study financial networks in collaboration with the team of professor Sabine Dörry at the Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research.

But why am I at the department of geography instead of economics? In other words, what exactly is financial geography? I have to admit that I didn’t know until a couple of months ago.

This post is an attempt to describe what financial geography is, and what sets it apart from other fields that study finance.

Location, location, location

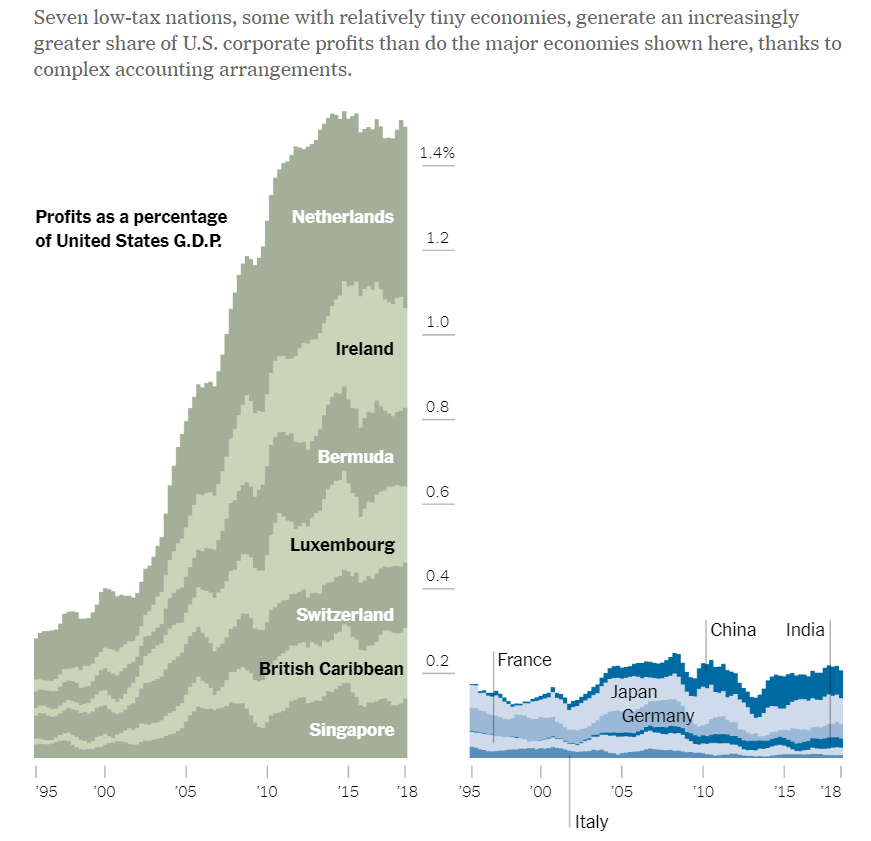

It is obvious that nations play an important role in the world economy. Just think about Trump’s trade war with China. Or the the fact that multinationals book most of their profits in countries with favorable tax laws.

These hot topics are studied in international economics, a field where economics meets political science and stuff like taxation. “Geography” is relevant because sovereign states determine the policies and laws in their respective territories1. That makes the nation state the ‘natural unit’ in the analysis of international finance scholars.

Geographers don’t let borders limit their investigations. They look at all kinds of phenomena that have a spatial dimension (e.g. transport, crime or migration).

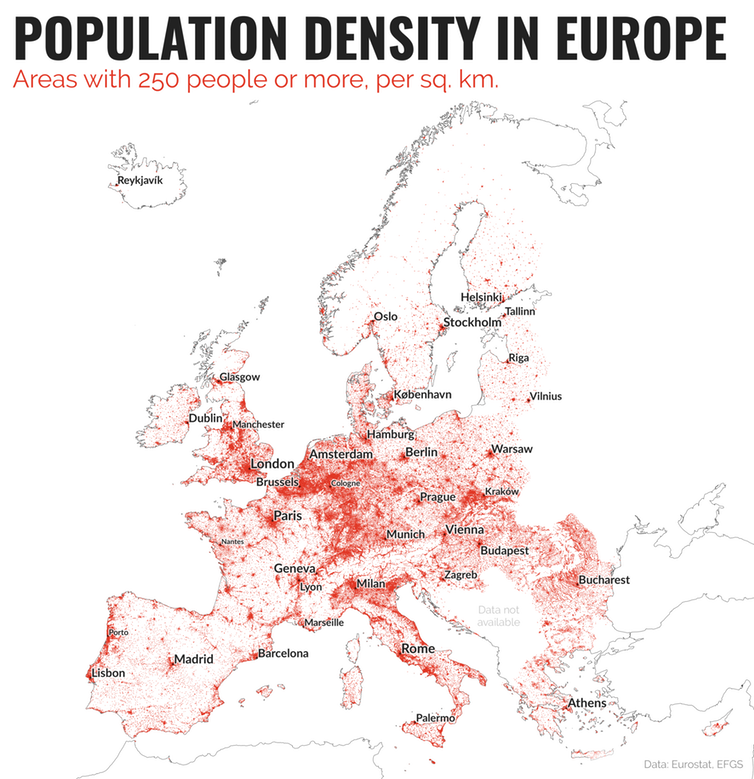

Take population density as a non-financial example of how geographers think. Calculating the population density of a country is straightforward: divide the number of inhabitants by the surface area. However, the average population density doesn’t tell you much about the experience of people. The map below shows that Spain is relatively ’empty’, but people are packed together in a number of places.

So the ‘lived density‘ in Spain is much higher than one might naively expect based on its average population density.

Cities and networks

Now let’s add finance to the geographic picture.

Financial firms are clustered in places like Wall Street, the City of London, Hong Kong, and the tax havens mentioned earlier. These financial centers are nodes in a network that moves money, information and professionals.

Geographers study the ‘dynamics’ of such financial centers. For example, Sigler and Croft investigated the links between tax havens. What’s the effect of the global financial crisis and Brexit on international financial centers? Cassis, Wójcik et al. have written a book about it. Van Meeteren published a geographer’s perspective on financial integration in the EU. Pan, Hall and Zhang studied the emergence of Beijing as a financial center. Other authors focused on individual firms like SWIFT or Goldman Sachs.

Common threads in all of these studies are the emphasis on places, the people who shape them, and the relations between them.

In summary, my tentative definition: financial geography is the study of how financial networks evolve on a global scale.

Meet me in Beijing!

I have only scratched the surface of a very diverse subject. If you’re a financial geographer who thinks this is all wrong, let me know in the comments. Or better yet, tell me in person! I’ll be at the 1st FinGeo Global Conference 2019 in Beijing.